Feastday: October 18

Patron: Physicians and Surgeons

Luke, the writer of the Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles, has been identified with St. Paul's "Luke, the beloved physician" (Colossians 4:14). We know few other facts about Luke's life from Scripture and from early Church historians.

It is believed that Luke was born a Greek and a Gentile. In Colossians 10-14 speaks of those friends who are with him. He first mentions all those "of the circumcision" -- in other words, Jews -- and he does not include Luke in this group. Luke's gospel shows special sensitivity to evangelizing Gentiles. It is only in his gospel that we hear the parable of the Good Samaritan, that we hear Jesus praising the faith of Gentiles such as the widow of Zarephath and Naaman the Syrian (Lk.4:25-27), and that we hear the story of the one grateful leper who is a Samaritan (Lk.17:11-19). According to the early Church historian Eusebius Luke was born at Antioch in Syria.

In our day, it would be easy to assume that someone who was a doctor was rich, but scholars have argued that Luke might have been born a slave. It was not uncommon for families to educate slaves in medicine so that they would have a resident family physician. Not only do we have Paul's word, but Eusebius, Saint Jerome, Saint Irenaeus and Caius, a second-century writer, all refer to Luke as a physician.

We have to go to Acts to follow the trail of Luke's Christian ministry. We know nothing about his conversion but looking at the language of Acts we can see where he joined Saint Paul. The story of the Acts is written in the third person, as an historian recording facts, up until the sixteenth chapter. In Acts 16:8-9 we hear of Paul's company "So, passing by Mysia, they went down to Troas. During the night Paul had a vision: there stood a man of Macedonia pleading with him and saying, 'Come over to Macedonia and help us.' " Then suddenly in 16:10 "they" becomes "we": "When he had seen the vision, we immediately tried to cross over to Macedonia, being convinced that God had called us to proclaim the good news to them."

So Luke first joined Paul's company at Troas at about the year 51 and accompanied him into Macedonia where they traveled first to Samothrace, Neapolis, and finally Philippi. Luke then switches back to the third person which seems to indicate he was not thrown into prison with Paul and that when Paul left Philippi Luke stayed behind to encourage the Church there. Seven years passed before Paul returned to the area on his third missionary journey. In Acts 20:5, the switch to "we" tells us that Luke has left Philippi to rejoin Paul in Troas in 58 where they first met up. They traveled together through Miletus, Tyre, Caesarea, to Jerusalem.

Luke is the loyal comrade who stays with Paul when he is imprisoned in Rome about the year 61: "Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends greetings to you, and so do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my fellow workers" (Philemon 24). And after everyone else deserts Paul in his final imprisonment and sufferings, it is Luke who remains with Paul to the end: "Only Luke is with me" (2 Timothy 4:11).

Luke's inspiration and information for his Gospel and Acts came from his close association with Paul and his companions as he explains in his introduction to the Gospel: "Since many have undertaken to set down an orderly account of the events that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed on to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, I too decided, after investigating everything carefully from the very first, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus" (Luke 1:1-3).

Luke's unique perspective on Jesus can be seen in the six miracles and eighteen parables not found in the other gospels. Luke's is the gospel of the poor and of social justice. He is the one who tells the story of Lazarus and the Rich Man who ignored him. Luke is the one who uses "Blessed are the poor" instead of "Blessed are the poor in spirit" in the beatitudes. Only in Luke's gospel do we hear Mary 's Magnificat where she proclaims that God "has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty" (Luke 1:52-53).

Luke also has a special connection with the women in Jesus' life, especially Mary. It is only in Luke's gospel that we hear the story of the Annunciation, Mary's visit to Elizabeth including the Magnificat, the Presentation, and the story of Jesus' disappearance in Jerusalem. It is Luke that we have to thank for the Scriptural parts of the Hail Mary: "Hail Mary full of grace" spoken at the Annunciation and "Blessed are you and blessed is the fruit of your womb Jesus" spoken by her cousin Elizabeth.

Forgiveness and God's mercy to sinners is also of first importance to Luke. Only in Luke do we hear the story of the Prodigal Son welcomed back by the overjoyed father. Only in Luke do we hear the story of the forgiven woman disrupting the feast by washing Jesus' feet with her tears. Throughout Luke's gospel, Jesus takes the side of the sinner who wants to return to God's mercy.

Reading Luke's gospel gives a good idea of his character as one who loved the poor, who wanted the door to God's kingdom opened to all, who respected women, and who saw hope in God's mercy for everyone.

The reports of Luke's life after Paul's death are conflicting. Some early writers claim he was martyred, others say he lived a long life. Some say he preached in Greece, others in Gaul. The earliest tradition we have says that he died at 84 Boeotia after settling in Greece to write his Gospel.

A tradition that Luke was a painter seems to have no basis in fact. Several images of Mary appeared in later centuries claiming him as a painter but these claims were proved false. Because of this tradition, however, he is considered a patron of painters of pictures and is often portrayed as painting pictures of Mary.

He is often shown with an ox or a calf because these are the symbols of sacrifice -- the sacrifice Jesus made for all the world.

Luke is the patron of physicians and surgeons.

One of the four traditionally ascribed authors of the canonical gospels "Saint Luke" redirects here. For other uses, see Saint Luke (disambiguation).

Luke the Evangelist (Latin: Lucas; Ancient Greek: Λουκᾶς, Loukâs; Hebrew: לוקאס, Lūqās; Aramaic: /ܠܘܩܐ לוקא, Lūqā') is one of the Four Evangelists—the four traditionally ascribed authors of the canonical gospels. The Early Church Fathers ascribed to him authorship of both the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles, which would mean Luke contributed over a quarter of the text of the New Testament, more than any other author. Prominent figures in early Christianity such as Jerome and Eusebius later reaffirmed his authorship, although a lack of conclusive evidence as to the identity of the author of the works has led to discussion in scholarly circles, both secular and religious.

The New Testament mentions Luke briefly a few times, and the Pauline Epistle to the Colossians refers to him as a physician (from Greek for 'one who heals'); thus he is thought to have been both a physician and a disciple of Paul. Since the early years of the faith, Christians have regarded him as a saint. He is believed to have been a martyr, reportedly having been hanged from an olive tree, though some believe otherwise.

The Catholic Church and other major denominations venerate him as Saint Luke the Evangelist and as a patron saint of artists, physicians, bachelors, surgeons, students and butchers; his feast day is 18 October.

Luke the Evangelist is remembered in the Church of England with a Festival on 18 October.

Life

Print of Luke the Evangelist. Made by Crispijn van de Passe de Oude.

Print of Luke the Evangelist. Made by Crispijn van de Passe de Oude.

Many scholars believe that Luke was a Greek physician who lived in the Greek city of Antioch in Ancient Syria, although some other scholars and theologians think Luke was a Hellenic Jew. Bart Koet, a researcher and professor of theology, has stated that it was widely accepted that the theology of Luke–Acts points to a gentile Christian writing for a gentile audience, although he concludes that it is more plausible that Luke–Acts is directed to a community made up of both Jewish and gentile Christians because there is stress on the scriptural roots of the gentile mission (see the use of Isaiah 49:6 in Luke–Acts). Gregory Sterling, Dean of the Yale Divinity School, claims that he was either a Hellenistic Jew or a god-fearer.

His earliest notice is in Paul's Epistle to Philemon—. He is also mentioned in Colossians 4:14 and 2 Timothy 4:11, two Pauline works. The next earliest account of Luke is in the Anti-Marcionite Prologue to the Gospel of Luke, a document once thought to date to the 2nd century, but which has more recently been dated to the later 4th century. Helmut Koester, however, claims that the following part, the only part preserved in the original Greek, may have been composed in the late 2nd century:

James Tissot, Saint Luke (Saint Luc), Brooklyn Museum

James Tissot, Saint Luke (Saint Luc), Brooklyn Museum

Epiphanius states that Luke was one of the Seventy Apostles (Panarion 51.11), and John Chrysostom indicates at one point that the "brother" Paul mentions in the Second Epistle to the Corinthians 8:18 is either Luke or Barnabas. (Homily 18 on Second Corinthians on 2 Corinthians 8:18)

If one accepts that Luke was indeed the author of the Gospel bearing his name and also the Acts of the Apostles, certain details of his personal life can be reasonably assumed. While he does exclude himself from those who were eyewitnesses to Jesus' ministry, he repeatedly uses the word "we" in describing the Pauline missions in Acts of the Apostles, indicating that he was personally there at those times.

There is similar evidence that Luke resided in Troas, the province which included the ruins of ancient Troy, in that he writes in Acts in the third person about Paul and his travels until they get to Troas, where he switches to the first person plural. The "we" section of Acts continues until the group leaves Philippi, when his writing goes back to the third person. This change happens again when the group returns to Philippi. There are three "we sections" in Acts, all following this rule. Luke never stated, however, that he lived in Troas, and this is the only evidence that he did.

Luke as depicted in the head-piece of an Armenian Gospel manuscript from 1609, held at the Bodleian Library

Luke as depicted in the head-piece of an Armenian Gospel manuscript from 1609, held at the Bodleian Library

The composition of the writings, as well as the range of vocabulary used, indicate that the author was an educated man. A quote in the Epistle to the Colossians differentiates between Luke and other colleagues "of the circumcision."

10 My fellow prisoner Aristarchus sends you his greetings, as does Mark, the cousin of Barnabas. 11 Jesus, who is called Justus, also sends greetings. These are the only Jews among my co-workers for the kingdom of God, and they have proved a comfort to me. ... 14 Our dear friend Luke, the doctor, and Demas send greetings.

— Colossians 4:10–11, 14.

This comment has traditionally caused commentators to conclude that Luke was a gentile. If this were true, it would make Luke the only writer of the New Testament who can clearly be identified as not being Jewish. However, that is not the only possibility. Although Luke is considered likely to have been a gentile Christian, some scholars believe him to have been a Hellenized Jew. The phrase could just as easily be used to differentiate between those Christians who strictly observed the rituals of Judaism and those who did not.

Luke's presence in Rome with the Apostle Paul near the end of Paul's life was attested by 2 Timothy 4:11: "Only Luke is with me". In the last chapter of the Book of Acts, widely attributed to Luke, there are several accounts in the first person also affirming Luke's presence in Rome, including Acts 28:16: "And when we came to Rome... ." According to some accounts, Luke also contributed to the authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews.

Luke died at age 84 in Boeotia, according to a "fairly early and widespread tradition". According to Nikephoros Kallistos Xanthopoulos, Greek historian of the 14th century (and others), Luke's tomb was located in Thebes, whence his relics were transferred to Constantinople in the year 357.

Authorship of Luke and Acts

See also: Authorship of Luke–ActsThe Gospel of Luke does not name its author.(Senior, Achtemeier & Karris 2002, p. 328) The Gospel was not, nor does it claim to be, written by direct witnesses to the reported events, unlike Acts beginning in the sixteenth chapter. However, in most translations the author suggests that they have investigated the book's events and notes the name (Theophilus) of that to whom they are writing.

The earliest manuscript of the Gospel (Papyrus 75 = Papyrus Bodmer XIV-XV), dated circa AD 200, ascribes the work to Luke; as did Irenaeus writing circa AD 180, and the Muratorian fragment, a 7th-century Latin manuscript thought to be copied and translated from a Greek manuscript as old as AD 170.

The Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles make up a two-volume work which scholars call Luke–Acts. Together they account for 27.5% of the New Testament, the largest contribution by a single author.

Luke paints the Madonna and the Baby Jesus, by Maarten van Heemskerck, 1532

Luke paints the Madonna and the Baby Jesus, by Maarten van Heemskerck, 1532

As a historian

See also: Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles, Census of Quirinius, and Chronology of Jesus A medieval Armenian illumination of Luke, by Toros Roslin

A medieval Armenian illumination of Luke, by Toros Roslin

Most scholars understand Luke's works (Luke–Acts) in the tradition of Greek historiography. The preface of The Gospel of Luke drawing on historical investigation identified the work to the readers as belonging to the genre of history. There is disagreement about how best to treat Luke's writings, with some historians regarding Luke as highly accurate, and others taking a more critical approach.

Based on his accurate description of towns, cities and islands, as well as correctly naming various official titles, archaeologist Sir William Ramsay wrote that "Luke is a historian of the first rank; not merely are his statements of fact trustworthy. ...[He] should be placed along with the very greatest of historians." Professor of Classics at Auckland University, E.M. Blaiklock, wrote: "For accuracy of detail, and for evocation of atmosphere, Luke stands, in fact, with Thucydides. The Acts of the Apostles is not shoddy product of pious imagining, but a trustworthy record. ...It was the spadework of archaeology which first revealed the truth." New Testament scholar Colin Hemer has made a number of advancements in understanding the historical nature and accuracy of Luke's writings.

On the purpose of Acts, New Testament Scholar Luke Timothy Johnson has noted that "Luke's account is selected and shaped to suit his apologetic interests, not in defiance of but in conformity to ancient standards of historiography." Such a position is shared by most commentators such as Richard Heard who sees historical deficiencies as arising from "special objects in writing and to the limitations of his sources of information."

During modern times, Luke's competence as a historian is questioned, depending upon one's a priori view of the supernatural. Since post-Enlightenment historians work with methodological naturalism, such historians would see a narrative that relates supernatural, fantastic things like angels, demons etc., as problematic as a historical source. Mark Powell claims that "it is doubtful whether the writing of history was ever Luke's intent. Luke wrote to proclaim, to persuade, and to interpret; he did not write to preserve records for posterity. An awareness of this, has been, for many, the final nail in Luke the historian's coffin."

Robert M. Grant has noted that although Luke saw himself within the historical tradition, his work contains a number of statistical improbabilities, such as the sizable crowd addressed by Peter in Acts 4:4. He has also noted chronological difficulties whereby Luke "has Gamaliel refer to Theudas and Judas in the wrong order, and Theudas actually rebelled about a decade after Gamaliel spoke (5:36–7)".

Brent Landau writes:

So how do we account for a Gospel that is believable about minor events but implausible about a major one? One possible explanation is that Luke believed that Jesus’ birth was of such importance for the entire world that he dramatically juxtaposed this event against an (imagined) act of worldwide domination by a Roman emperor who was himself called “savior” and “son of God”—but who was nothing of the sort. For an ancient historian following in the footsteps of Thucydides, such a procedure would have been perfectly acceptable.

As an artist

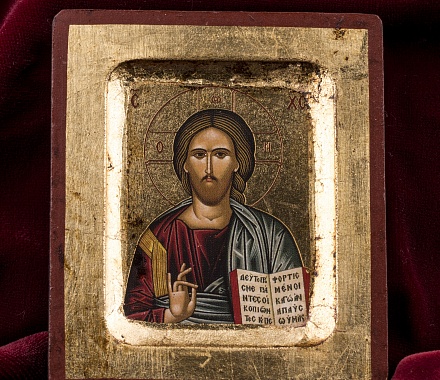

Luke the Evangelist painting the first icon of the Virgin Mary

Luke the Evangelist painting the first icon of the Virgin Mary

Christian tradition, starting from the 8th century, states that Luke was the first icon painter. He is said to have painted pictures of the Virgin Mary and Child, in particular the Hodegetria image in Constantinople (now lost). Starting from the 11th century, a number of painted images were venerated as his autograph works, including the Black Madonna of Częstochowa and Our Lady of Vladimir. He was also said to have painted Saints Peter and Paul, and to have illustrated a gospel book with a full cycle of miniatures.

Late medieval Guilds of Saint Luke in the cities of Late Medieval Europe, especially Flanders, or the "Accademia di San Luca" (Academy of Saint Luke) in Rome—imitated in many other European cities during the 16th century—gathered together and protected painters. The tradition that Luke painted icons of Mary and Jesus has been common, particularly in Eastern Orthodoxy. The tradition also has support from the Saint Thomas Christians of India who claim to still have one of the Theotokos icons that Saint Luke painted and which Saint Thomas brought to India.

Symbol

Luke and the Madonna, Altar of the Guild of Saint Luke, Hermen Rode, Lübeck (1484)

Luke and the Madonna, Altar of the Guild of Saint Luke, Hermen Rode, Lübeck (1484)

In traditional depictions, such as paintings, evangelist portraits, and church mosaics, Saint Luke is often accompanied by an ox or bull, usually having wings. Sometimes only the symbol is shown, especially when in a combination of those of all Four Evangelists.

Relics

Despot George of Serbia purportedly bought the relics from the Ottoman sultan Murad II for 30,000 gold coins. After the Ottoman conquest of Bosnia, the kingdom's last queen, George's granddaughter Mary, who had brought the relics with her from Serbia as her dowry, sold them to the Venetian Republic.

In 1992, the then Greek Orthodox Metropolitan Ieronymos of Thebes and Levathia (who subsequently became Archbishop Ieronymos II of Athens and All Greece) requested from Bishop Antonio Mattiazzo of Padua the return of "a significant fragment of the relics of St. Luke to be placed on the site where the holy tomb of the Evangelist is located and venerated today". This prompted a scientific investigation of the relics in Padua, and by numerous lines of empirical evidence (archeological analyses of the Tomb in Thebes and the Reliquary of Padua, anatomical analyses of the remains, carbon-14 dating, comparison with the purported skull of the Evangelist located in Prague) confirmed that these were the remains of an individual of Syrian descent who died between AD 72 and AD 416. The Bishop of Padua then delivered to Metropolitan Ieronymos the rib of Saint Luke that was closest to his heart to be kept at his tomb in Thebes.

Thus, the relics of Saint Luke are divided as follows:

- The body, in the Abbey of Santa Giustina in Padua;

- The head, in the St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague;

- A rib, at his tomb in Thebes.

Gallery

- Luke the Evangelist and artist

-

-

-

-

-

-