Feastday: December 27

Saint John the Divine as the son of Zebedee, and his mother's name was Salome [Matthew 4:21, 27:56; Mark 15:40, 16:1]. They lived on the shores of the sea of Galilee. The brother of Saint John, probably considerably older, was Saint James. The mention of the "hired men" [Mark 1:20], and of Saint John's "home" [John 19:27], implies that the condition of Salome and her children was not one of great poverty.

SS. John and James followed the Baptist when he preached repentance in the wilderness of Jordan. There can be little doubt that the two disciples, whom Saint John does not name (John 1:35), who looked on Jesus "as he walked," when the Baptist exclaimed with prophetic perception, "Behold the Lamb of God!" were Andrew and John. They followed and asked the Lord where he dwelt. He bade them come and see, and they stayed with him all day. Of the subject of conversation that took place in this interview no record has come to us, but it was probably the starting-point of the entire devotion of heart and soul which lasted through the life of the Beloved Apostle.

John apparently followed his new Master to Galilee, and was with him at the marriage feast of Cana, journeyed with him to Capernaum, and thenceforth never left him, save when sent on the missionary expedition with another, invested with the power of healing. He, James, and Peter, came within the innermost circle of their Lord's friends, and these three were suffered to remain with Christ when all the rest of the apostles were kept at a distance [Mark 5:37, Matthew 17:1, 26:37]. Peter, James, and John were with Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. The mother of James and John, knowing our Lord's love for the brethren, made special request for them, that they might sit, one on his right hand, the other on his left, in his kingdom [Matthew 20:21]. There must have been much impetuosity in the character of the brothers, for they obtained the nickname of Boanerges, Sons of Thunder [Mark 3:17, see also Luke 9:54]. It is not necessary to dwell on the familiar history of the Last Supper and the Passion. To John was committed by our Lord the highest of privileges, the care of his mother [John 19:27]. John [the "disciple whom Jesus loved"] and Peter were the first to receive the news from the Magdalene of the Resurrection [John 20:2], and they hastened at once to the sepulchre, and there when Peter was restrained by awe, John impetuously "reached the tomb first."

In the interval between the Resurrection and the Ascension, John and Peter were together on the Sea of Galilee [John 21:1], having returned to their old calling, and old familiar haunts.

When Christ appeared on the shore in the dusk of morning, John was the first to recognize him. The last words of the Gospel reveal the attachment which existed between the two apostles. It was not enough for Peter to know his own fate, he must learn also something of the future that awaited his friend. The Acts show us them still united, entering together as worshippers into the Temple [Acts 3:1], and protesting together against the threats of the Sanhedrin [Acts 4:13]. They were fellow-workers together in the first step of Church expansion. The apostle whose wrath had been kindled at the unbelief of the Samaritans, was the first to receive these Samaritans as brethren [Luke 9:54, Acts 8:14].

He probably remained at Jerusalem until the assumption of the Virgin, though tradition of no great antiquity or weight asserts that he took her to Ephesus. When he went to Ephesus is uncertain. He was at Jerusalem fifteen years after Saint Paul's first visit there [Acts 15:6]. There is no trace of his presence there when Saint Paul was at Jerusalem for the last time.

Tradition, more or less trustworthy, completes the history. Irenaeus says that Saint John did not settle at Ephesus until after the death SS. Peter and Paul, and this is probable. He certainly as not there when Saint Timothy was appointed bishop of that place. Saint Jerome says that he supervised and governed all the Churches of Asia. He probably took up his abode finally in Ephesus in 97. In the persecution of Domitian he was taken to Rome, and was placed in a cauldron of boiling oil, outside the Latin gate, without the boiling fluid doing him any injury. [Eusebius makes no mention of this. The legend of the boiling oil occurs in Tertullian and in Saint Jerome]. He was sent to labor at the mines in Patmos. At the accession of Nerva he was set free, and returned to Ephesus, and there it is thought that he wrote his gospel. Of his zeal and love combined we have examples in Eusebius, who tells, on the authority of Irenaeus, that Saint John once fled out of a bath on hearing that Cerinthus was in it, lest, as he asserted, the roof should fall in, and crush the heretic. On the other hand, he showed the love that was in him. He commended a young man in whom he was interested to a bishop, and bade him keep his trust well. Some years after he learned that the young man had become a robber. Saint John, though very old, pursued him among the mountain fastnesses, and by his tenderness recovered him.

In his old age, when unable to do more, he was carried into the assembly of the Church at Ephesus, and his sole exhortation was, "Little children, love one another."

The date of his death cannot be fixed with anything like precision, but it is certain that he lived to a very advanced age. He is represented holding a chalice from which issues a dragon, as he is supposed to have been given poison, which was, however, innocuous. Also his symbol is an eagle.

From The Lives of the Saints by the Rev. S. Baring-Gould, M.A., published in 1914 in Edinburgh.

Name traditionally given to the author of the Gospel of John

| Part of a series of articles on |

| John in the Bible |

|---|

Saint John the Evangelist, Domenichino Saint John the Evangelist, Domenichino |

| Johannine literature |

|

| Authorship |

|

| Related literature |

|

| See also |

|

|

John the Evangelist (Greek: Ἰωάννης, translit. Iōánnēs; Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ; Arabic: يوحنا الإنجيلي, Hebrew: יוחנן האוונגליסט Coptic: ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ) is the name traditionally given to the author of the Gospel of John. Christians have traditionally identified him with John the Apostle, John of Patmos, or John the Presbyter, although this has been disputed by most modern scholars.

Identity

See also: Johannine literature and Four Evangelists Print of John the Evangelist. Preserved in the Ghent University Library.

Print of John the Evangelist. Preserved in the Ghent University Library.

The Gospel of John refers to an otherwise unnamed "disciple whom Jesus loved", who "bore witness to and wrote" the Gospel's message. The author of the Gospel of John seemed interested in maintaining the internal anonymity of the author's identity, although interpreting the Gospel in the light of the Synoptic Gospels and considering that the author names (and therefore is not claiming to be) Peter, and that James was martyred as early as 44 AD, it has been widely believed that the author was the Apostle John (though some believe he was pretending to be).

Christian tradition says that John the Evangelist was John the Apostle. The Apostle John was one of the "pillars" of the Jerusalem church after Jesus' death. He was one of the original twelve apostles and is thought to be the only one to have not been killed for his faith. It had been believed that he was exiled (around 95 AD) to the Aegean island of Patmos, where he wrote the Book of Revelation. However, some attribute the authorship of Revelation to another man, called John the Presbyter, or to other writers of the late first century AD. Bauckham argues that the early Christians identified John the Evangelist with John the Presbyter.

Orthodox Roman Catholic scholarship, most Protestant churches, and the entire Eastern Orthodox Church attribute all of the Johannine literature to the same individual, the "Holy Apostle and Evangelist, John the Theologian", whom it identifies with the "Beloved Disciple" in the Gospel of John.

Authorship of the Johannine works

Main articles: Authorship of the Johannine works and Johannine epistlesThe authorship of the Johannine works has been debated by scholars since at least the 2nd century AD. The main debate centers on who authored the writings, and which of the writings, if any, can be ascribed to a common author.

Eastern Orthodox tradition attributes all of the Johannine books to John the Apostle.

In the 6th century, the Decretum Gelasianum argued that Second and Third John have a separate author known as "John, a priest" (see John the Presbyter). Historical critics, like H.P.V. Nunn, the non-Christians Reza Aslan, Richard Carrier, and Bart Ehrman, reject the view that John the Apostle authored any of these works.

Most modern scholars believe that the apostle John wrote none of these works, although some, such as J.A.T. Robinson, F. F. Bruce, Leon Morris, and Martin Hengel, hold the apostle to be behind at least some, in particular the gospel.

There may have been a single author for the gospel and the three epistles. Some scholars conclude the author of the epistles was different from that of the gospel, although all four works originated from the same community. The gospel and epistles traditionally and plausibly came from Ephesus, c. 90–110, although some scholars argue for an origin in Syria.

In the case of Revelation, most modern scholars agree that it was written by a separate author, John of Patmos, c. 95 with some parts possibly dating to Nero's reign in the early 60s.

Feast day

The feast day of Saint John in the Catholic Church, Anglican Communion, and the Lutheran Calendar, is on 27 December, the third day of Christmastide. In the Tridentine Calendar he was commemorated also on each of the following days up to and including 3 January, the Octave of the 27 December feast. This Octave was abolished by Pope Pius XII in 1955. The traditional liturgical color is white.

Freemasons celebrate this feast day, dating back to the 18th century when the Feast Day was used for the installation of Presidents and Grand Masters.

In art

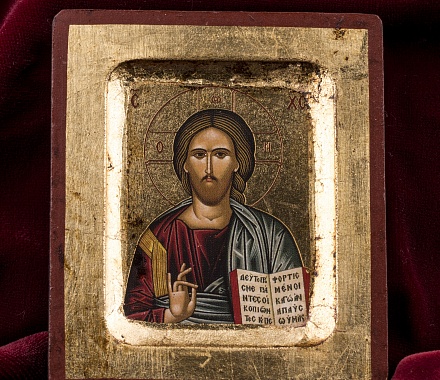

John is traditionally depicted in one of two distinct ways: either as an aged man with a white or gray beard, or alternatively as a beardless youth. The first way of depicting him was more common in Byzantine art, where it was possibly influenced by antique depictions of Socrates; the second was more common in the art of Medieval Western Europe and can be dated back as far as 4th century Rome.

In medieval works of painting, sculpture and literature, Saint John is often presented in an androgynous or feminized manner. Historians have related such portrayals to the circumstances of the believers for whom they were intended. For instance, John's feminine features are argued to have helped to make him more relatable to women. Likewise, Sarah McNamer argues that because of John's androgynous status, he could function as an 'image of a third or mixed gender' and 'a crucial figure with whom to identify' for male believers who sought to cultivate an attitude of affective piety, a highly emotional style of devotion that, in late-medieval culture, was thought to be poorly compatible with masculinity.

Legends from the Acts of John contributed much to medieval iconography; it is the source of the idea that John became an apostle at a young age. One of John's familiar attributes is the chalice, often with a snake emerging from it. According to one legend from the Acts of John, John was challenged to drink a cup of poison to demonstrate the power of his faith, and thanks to God's aid the poison was rendered harmless. The chalice can also be interpreted with reference to the Last Supper, or to the words of Christ to John and James: "My chalice indeed you shall drink." According to the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia, some authorities believe that this symbol was not adopted until the 13th century. There was also a legend that John was at some stage boiled in oil and miraculously preserved. Another common attribute is a book or a scroll, in reference to his writings. John the Evangelist is symbolically represented by an eagle, one of the creatures envisioned by Ezekiel (1:10) and in the Book of Revelation (4:7).

Gallery

- John the Evangelist

-

St. John the Evangelist by Joan de Joanes (1507–1579), oil on panel

-

Saint John the Evangelist by Domenichino (1621–29)

-

Saint John the Evangelist on Patmos, 1490

-

Piero di Cosimo, Saint John the Evangelist, oil on panel, 1504–6, Honolulu Museum of Art

-

The Vision of Saint John (1608–1614), by El Greco

-

Saint John the Evangelist in meditation by Simone Cantarini

(1612–1648), Bologna -

Saints John and Bartholomew, by Dosso Dossi

-

Stained glass window in St. Aidan’s Cathedral, Ireland

-

Saint John and the Poisoned Cup by Alonzo Cano

Spain (1635–1637) -

Saint John and the eagle by Vladimir Borovikovsky in Kazan Cathedral, Saint Petersburg

-

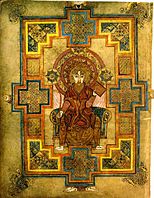

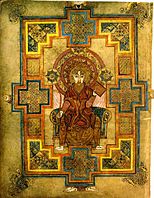

A portrait from the Book of Kells, c. 800

-

Saint John and the cup by El Greco

-

Statue of John the Evangelist outside St. John's Seminary, Boston

-

St John the Evangelist depicted in a 14th-century manuscript in the Flemish style

-

St John the Evangelist, by Francisco Pacheco (1608, Museo del Prado)

-

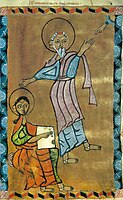

Prochorus and St John depicted in Xoranasat's gospel manuscript in 1224. Armenian manuscript.