Feastday: January 17

Two Greek philosophers ventured out into the Egyptian desert to the mountain where Anthony lived. When they got there, Anthony asked them why they had come to talk to such a foolish man? He had reason to say that -- they saw before them a man who wore a skin, who refused to bathe, who lived on bread and water. They were Greek, the world's most admired civilization, and Anthony was Egyptian, a member of a conquered nation. They were philosophers, educated in languages and rhetoric. Anthony had not even attended school as a boy and he needed an interpreter to speak to them. In their eyes, he would have seemed very foolish.

But the Greek philosophers had heard the stories of Anthony. They had heard how disciples came from all over to learn from him, how his intercession had brought about miraculous healings, how his words comforted the suffering. They assured him that they had come to him because he was a wise man.

Anthony guessed what they wanted. They lived by words and arguments. They wanted to hear his words and his arguments on the truth of Christianity and the value of ascetism. But he refused to play their game. He told them that if they truly thought him wise, "If you think me wise, become what I am, for we ought to imitate the good. Had I gone to you, I should have imitated you, but, since you have come to me, become what I am, for I am a Christian."

Anthony's whole life was not one of observing, but of becoming. When his parents died when he was eighteen or twenty he inherited their three hundred acres of land and the responsibility for a young sister. One day in church, he heard read Matthew 19:21: "If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me." Not content to sit still and meditate and reflect on Jesus' words he walked out the door of the church right away and gave away all his property except what he and his sister needed to live on. On hearing Matthew 6:34, "So do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will bring worries of its own. Today's trouble is enough for today," he gave away everything else, entrusted his sister to a convent, and went outside the village to live a life of praying, fasting, and manual labor. It wasn't enough to listen to words, he had to become what Jesus said.

Every time he heard of a holy person he would travel to see that person. But he wasn't looking for words of wisdom, he was looking to become. So if he admired a person's constancy in prayer or courtesy or patience, he would imitate it. Then he would return home.

Anthony went on to tell the Greek philosophers that their arguments would never be as strong as faith. He pointed out that all rhetoric, all arguments, no matter how complex, how well-founded, were created by human beings. But faith was created by God. If they wanted to follow the greatest ideal, they should follow their faith.

Anthony knew how difficult this was. Throughout his life he argued and literally wrestled with the devil. His first temptations to leave his ascetic life were arguments we would find hard to resist -- anxiety about his sister, longings for his relatives, thoughts of how he could have used his property for good purposes, desire for power and money. When Anthony was able to resist him, the devil then tried flattery, telling Anthony how powerful Anthony was to beat him. Anthony relied on Jesus' name to rid himself of the devil. It wasn't the last time, though. One time, his bout with the devil left him so beaten, his friends thought he was dead and carried him to church. Anthony had a hard time accepting this. After one particular difficult struggle, he saw a light appearing in the tomb he lived in. Knowing it was God, Anthony called out, "Where were you when I needed you?" God answered, "I was here. I was watching your struggle. Because you didn't give in, I will stay with you and protect you forever."

With that kind of assurance and approval from God, many people would have settled in, content with where they were. But Anthony's reaction was to get up and look for the next challenge -- moving out into the desert.

Anthony always told those who came to visit him that the key to the ascetic life was perseverance, not to think proudly, "We've lived an ascetic life for a long time" but treat each day as if it were the beginning. To many, perseverance is simply not giving up, hanging in there. But to Anthony perseverance meant waking up each day with the same zeal as the first day. It wasn't enough that he had given up all his property one day. What was he going to do the next day?

Once he had survived close to town, he moved into the tombs a little farther away. After that he moved out into the desert. No one had braved the desert before. He lived sealed in a room for twenty years, while his friends provided bread. People came to talk to him, to be healed by him, but he refused to come out. Finally they broke the door down. Anthony emerged, not angry, but calm. Some who spoke to him were healed physically, many were comforted by his words, and others stayed to learn from him. Those who stayed formed what we think of as the first monastic community, though it is not what we would think of religious life today. All the monks lived separately, coming together only for worship and to hear Anthony speak.

But after awhile, too many people were coming to seek Anthony out. He became afraid that he would get too proud or that people would worship him instead of God. So he took off in the middle of the night, thinking to go to a different part of Egypt where he was unknown. Then he heard a voice telling him that the only way to be alone was to go into the desert. He found some Saracens who took him deep into the desert to a mountain oasis. They fed him until his friends found him again.

Anthony died when he was one hundred and five years old. A life of solitude, fasting, and manual labor in the service of God had left him a healthy, vigorous man until very late in life. And he never stopped challenging himself to go one step beyond in his faith.

Saint Athanasius, who knew Anthony and wrote his biography, said, "Anthony was not known for his writings nor for his worldly wisdom, nor for any art, but simply for his reverence toward God." We may wonder nowadays at what we can learn from someone who lived in the desert, wore skins, ate bread, and slept on the ground. We may wonder how we can become him. We can become Anthony by living his life of radical faith and complete commitment to God.

In His Footsteps: Fast for one day, if possible, as Anthony did, eating only bread and only after the sun sets. Pray as you do that God will show you how dependent you are on God for your strength.

Prayer: Saint Anthony, you spoke of the importance of persevering in our faith and our practice. Help us to wake up each day with new zeal for the Christian life and a desire to take the next challenge instead of just sitting still. Amen

Christian saint, monk, and hermit For other uses, see Saint Anthony (disambiguation). "Antonious" redirects here. For other uses, see Antonius. "San Antonio Abad" redirects here. For the Spanish district in Cartagena, see San Antonio Abad, Cartagena. For the Mexico City Metro station, see San Antonio Abad metro station.This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Anthony or Antony the Great (Greek: Ἀντώνιος Antṓnios; Arabic: القديس أنطونيوس الكبير; Latin: Antonius; Coptic: Ⲁⲃⲃⲁ Ⲁⲛⲧⲱⲛⲓ; c. 12 January 251 – 17 January 356), was a Christian monk from Egypt, revered since his death as a saint. He is distinguished from other saints named Anthony such as Anthony of Padua, by various epithets of his own: Saint Anthony, Anthony of Egypt, Anthony the Abbot, Anthony of the Desert, Anthony the Anchorite, Anthony the Hermit, and Anthony of Thebes. For his importance among the Desert Fathers and to all later Christian monasticism, he is also known as the Father of All Monks. His feast day is celebrated on 17 January among the Orthodox and Catholic churches and on Tobi 22 in the Coptic calendar.

The biography of Anthony's life by Athanasius of Alexandria helped to spread the concept of Christian monasticism, particularly in Western Europe via its Latin translations. He is often erroneously considered the first Christian monk, but as his biography and other sources make clear, there were many ascetics before him. Anthony was, however, among the first known to go into the wilderness (about AD 270), which seems to have contributed to his renown. Accounts of Anthony enduring supernatural temptation during his sojourn in the Eastern Desert of Egypt inspired the often-repeated subject of the temptation of St. Anthony in Western art and literature.

Anthony is appealed to against infectious diseases, particularly skin diseases. In the past, many such afflictions, including ergotism, erysipelas, and shingles, were referred to as St. Anthony's fire.

Life of Anthony

Most of what is known about Anthony comes from the Life of Anthony. Written in Greek around 360 by Athanasius of Alexandria, it depicts Anthony as an illiterate and holy man who through his existence in a primordial landscape has an absolute connection to the divine truth, which always is in harmony with that of Athanasius as the biographer.

A continuation of the genre of secular Greek biography, it became his most widely read work. Sometime before 374 it was translated into Latin by Evagrius of Antioch. The Latin translation helped the Life become one of the best known works of literature in the Christian world, a status it would hold through the Middle Ages.

Translated into several languages, it became something of a best seller in its day and played an important role in the spreading of the ascetic ideal in Eastern and Western Christianity. It later served as an inspiration to Christian monastics in both the East and the West, and helped to spread the concept of Christian monasticism, particularly in Western Europe via its Latin translations.

Many stories are also told about Anthony in various collections of sayings of the Desert Fathers.

Anthony probably spoke only his native language, Coptic, but his sayings were spread in a Greek translation. He himself dictated letters in Coptic, seven of which are extant.

Life

Early years

Anthony was born in Coma in Lower Egypt to wealthy landowner parents. When he was about 20 years old, his parents died and left him with the care of his unmarried sister. Shortly thereafter, he decided to follow the gospel exhortation in Matthew 19: 21, "If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasures in heaven." Anthony gave away some of his family's lands to his neighbors, sold the remaining property, and donated the funds to the poor. He then left to live an ascetic life, placing his sister with a group of Christian virgins.

Hermit

Painting of Saint Anthony, a part of The Visitation with Saint Nicholas and Saint Anthony Abbot by Piero di Cosimo, c. 1480

Painting of Saint Anthony, a part of The Visitation with Saint Nicholas and Saint Anthony Abbot by Piero di Cosimo, c. 1480

For the next fifteen years, Anthony remained in the area, spending the first years as the disciple of another local hermit. There are various legends that he worked as a swineherd during this period.

Anthony is sometimes considered the first monk, and the first to initiate solitary desertification, but there were others before him. There were already ascetic hermits (the Therapeutae), and loosely organized cenobitic communities were described by the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria in the 1st century AD as long established in the harsh environment of Lake Mareotis and in other less accessible regions. Philo opined that "this class of persons may be met with in many places, for both Greece and barbarian countries want to enjoy whatever is perfectly good." Christian ascetics such as Thecla had likewise retreated to isolated locations at the outskirts of cities. Anthony is notable for having decided to surpass this tradition and headed out into the desert proper. He left for the alkaline Nitrian Desert (later the location of the noted monasteries of Nitria, Kellia, and Scetis) on the edge of the Western Desert about 95 km (59 mi) west of Alexandria. He remained there for 13 years.

Anthony maintained a very strict ascetic diet. He ate only bread, salt and water and never meat or wine. He ate at most only once a day and sometimes fasted through two or four days.

According to Athanasius, the devil fought Anthony by afflicting him with boredom, laziness, and the phantoms of women, which he overcame by the power of prayer, providing a theme for Christian art. After that, he moved to one of the tombs near his native village. There it was that the Life records those strange conflicts with demons in the shape of wild beasts, who inflicted blows upon him, and sometimes left him nearly dead.

After fifteen years of this life, at the age of thirty-five, Anthony determined to withdraw from the habitations of men and retire in absolute solitude. He went into the desert to a mountain by the Nile called Pispir (now Der-el-Memun), opposite Arsinoë. There he lived strictly enclosed in an old abandoned Roman fort for some 20 years. Food was thrown to him over the wall. He was at times visited by pilgrims, whom he refused to see; but gradually a number of would-be disciples established themselves in caves and in huts around the mountain. Thus a colony of ascetics was formed, who begged Anthony to come forth and be their guide in the spiritual life. Eventually, he yielded to their importunities and, about the year 305, emerged from his retreat. To the surprise of all, he appeared to be not emaciated, but healthy in mind and body.

For five or six years he devoted himself to the instruction and organization of the great body of monks that had grown up around him; but then he once again withdrew into the inner desert that lay between the Nile and the Red Sea, near the shore of which he fixed his abode on a mountain where still stands the monastery that bears his name, Der Mar Antonios. Here he spent the last forty-five years of his life, in a seclusion, not so strict as Pispir, for he freely saw those who came to visit him, and he used to cross the desert to Pispir with considerable frequency. Amid the Diocletian Persecutions, around 311 Anthony went to Alexandria and was conspicuous visiting those who were imprisoned.

Father of Monks

Four tales on Anthony the Great by Vitale da Bologna, c. 1340, at the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

Four tales on Anthony the Great by Vitale da Bologna, c. 1340, at the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

Anthony was not the first ascetic or hermit, but he may properly be called the "Father of Monasticism" in Christianity, as he organized his disciples into a community and later, following the spread of Athanasius's hagiography, was the inspiration for similar communities throughout Egypt and, elsewhere. Macarius the Great was a disciple of Anthony. Visitors traveled great distances to see the celebrated holy man. Anthony is said to have spoken to those of a spiritual disposition, leaving the task of addressing the more worldly visitors to Macarius. Macarius later founded a monastic community in the Scetic desert.

The fame of Anthony spread and reached Emperor Constantine, who wrote to him requesting his prayers. The brethren were pleased with the Emperor's letter, but Anthony was not overawed and wrote back exhorting the Emperor and his sons not to esteem this world but remember the next.

The stories of the meeting of Anthony and Paul of Thebes, the raven who brought them bread, Anthony being sent to fetch the cloak given him by "Athanasius the bishop" to bury Paul's body in, and Paul's death before he returned, are among the familiar legends of the Life. However, belief in the existence of Paul seems to have existed quite independently of the Life.

In 338, he left the desert temporarily to visit Alexandria to help refute the teachings of Arius.

Final days

When Anthony sensed his death approaching, he commanded his disciples to give his staff to Macarius of Egypt, and to give one sheepskin cloak to Athanasius of Alexandria and the other sheepskin cloak to Serapion of Thmuis, his disciple. Anthony was interred, according to his instructions, in a grave next to his cell.

A copy by the young Michelangelo after an engraving by Martin Schongauer around 1487–1489, The Torment of Saint Anthony. Oil and tempera on panel. One of many artistic depictions of Saint Anthony's trials in the desert.

A copy by the young Michelangelo after an engraving by Martin Schongauer around 1487–1489, The Torment of Saint Anthony. Oil and tempera on panel. One of many artistic depictions of Saint Anthony's trials in the desert.

Temptation

See also: Temptation of Saint Anthony in visual artsAccounts of Anthony enduring supernatural temptation during his sojourn in the Eastern Desert of Egypt inspired the often-repeated subject of the temptation of St. Anthony in Western art and literature.

Anthony is said to have faced a series of supernatural temptations during his pilgrimage to the desert. The first to report on the temptation was his contemporary Athanasius of Alexandria. It is possible these events, like the paintings, are full of rich metaphor or in the case of the animals of the desert, perhaps a vision or dream. Emphasis on these stories, however, did not really begin until the Middle Ages when the psychology of the individual became of greater interest.

Some of the stories included in Anthony's biography are perpetuated now mostly in paintings, where they give an opportunity for artists to depict their more lurid or bizarre interpretations. Many artists, including Martin Schongauer, Hieronymus Bosch, Dorothea Tanning, Max Ernst, Leonora Carrington and Salvador Dalí, have depicted these incidents from the life of Anthony; in prose, the tale was retold and embellished by Gustave Flaubert in The Temptation of Saint Anthony.

The satyr and the centaur

The Meeting of Saint Anthony and Saint Paul of Thebes, Master of the Osservanza, 15th century, with the centaur at the background.

The Meeting of Saint Anthony and Saint Paul of Thebes, Master of the Osservanza, 15th century, with the centaur at the background.

Anthony was on a journey in the desert to find Paul of Thebes, who according to his dream was a better Hermit than he. Anthony had been under the impression that he was the first person to ever dwell in the desert; however, due to the dream, Anthony was called into the desert to find his "better", Paul. On his way there, he ran into two creatures in the forms of a centaur and a satyr. Although chroniclers sometimes postulated they might have been living beings, Western theology considers to have been demons.

While traveling through the desert, Anthony first found the centaur, a "creature of mingled shape, half horse half-man," whom he asked about directions. The creature tried to speak in an unintelligible language, but ultimately pointed with his hand the way desired, and then ran away and vanished from sight. It was interpreted as a demon trying to terrify him, or alternately a creature engendered by the desert.

Anthony found next the satyr, a "a manikin with hooked snout, horned forehead, and extremities like goats's feet." This creature was peaceful and offered him fruits, and when Anthony asked who he was, the satyr replied, "I'm a mortal being and one of those inhabitants of the desert whom the Gentiles deluded by various forms of error worship under the names of Fauns, Satyrs, and Incubi. I am sent to represent my tribe. We pray you in our behalf to entreat the favor of your Lord and ours, who, we have learnt, came once to save the world, and 'whose sound has gone forth into all the earth.'" Upon hearing this, Anthony was overjoyed and rejoiced over the glory of Christ. He condemned the city of Alexandria for worshipping monsters instead of God while beasts like the satyr spoke about Christ.

Silver and gold

Another time Anthony was travelling in the desert and found a plate of silver coins in his path.

Demons in the cave

Once, Anthony tried hiding in a cave to escape the demons that plagued him. There were so many little demons in the cave though that Anthony's servant had to carry him out because they had beaten him to death. When the hermits were gathered to Anthony's corpse to mourn his death, Anthony was revived. He demanded that his servants take him back to that cave where the demons had beaten him. When he got there he called out to the demons, and they came back as wild beasts to rip him to shreds. All of a sudden a bright light flashed, and the demons ran away. Anthony knew that the light must have come from God, and he asked God where he was before when the demons attacked him. God replied, "I was here but I would see and abide to see thy battle, and because thou hast mainly fought and well maintained thy battle, I shall make thy name to be spread through all the world."

Veneration

Pilgrimage banners from the shrine in Warfhuizen

Pilgrimage banners from the shrine in Warfhuizen

Anthony had been secretly buried on the mountain-top where he had chosen to live. His remains were reportedly discovered in 361, and transferred to Alexandria. Some time later, they were taken from Alexandria to Constantinople, so that they might escape the destruction being perpetrated by invading Saracens. In the eleventh century, the Byzantine emperor gave them to the French Count Jocelin. Jocelin had them transferred to La-Motte-Saint-Didier, later renamed. There, Jocelin undertook to build a church to house the remains, but died before the church was even started. The building was finally erected in 1297 and became a centre of veneration and pilgrimage, known as Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye.

Anthony is credited with assisting in a number of miraculous healings, primarily from ergotism, which became known as "St. Anthony's Fire". He was credited by two local noblemen of assisting them in recovery from the disease. They then founded the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony in honor of him, who specialized in nursing the victims of skin diseases.

Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye, Isère, France

Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye, Isère, France

Stained glass windows, Saint-Antoine l'Abbaye, Isère, France

Stained glass windows, Saint-Antoine l'Abbaye, Isère, France

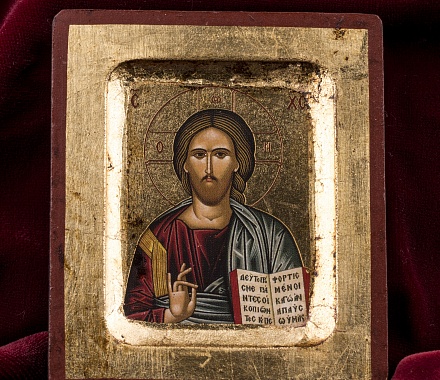

Veneration of Anthony in the East is more restrained. There are comparatively few icons and paintings of him. He is, however, regarded as the "first master of the desert and the pinnacle of holy monks", and there are monastic communities of the Maronite, Chaldean, and Orthodox churches which state that they follow his monastic rule. During the Middle Ages, Anthony, along with Quirinus of Neuss, Cornelius and Hubertus, was venerated as one of the Four Holy Marshals (Vier Marschälle Gottes) in the Rhineland.

Anthony is remembered in the Anglican Communion with a Lesser Festival on 17 January.

Legacy

The former main altar of the hermitage church in Warfhuizen in the Netherlands with a mural of Anthony the Abbot and a reliquary with some of his relics. Since then they have been moved to a new golden shrine on a side altar

The former main altar of the hermitage church in Warfhuizen in the Netherlands with a mural of Anthony the Abbot and a reliquary with some of his relics. Since then they have been moved to a new golden shrine on a side altar

Though Anthony himself did not organize or create a monastery, a community grew around him based on his example of living an ascetic and isolated life. Athanasius' biography helped propagate Anthony's ideals. Athanasius writes, "For monks, the life of Anthony is a sufficient example of asceticism."

Coptic literature

| Part of a series on | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Christian mysticism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Theology · Philosophy

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Practices

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

People (by era or century)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Literature · Media

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Examples of purely Coptic literature are the works of Anthony and Pachomius, who only spoke Coptic, and the sermons and preachings of Shenouda the Archmandrite, who chose to only write in Coptic. The earliest original writings in Coptic language were the letters by Anthony. During the 3rd and 4th centuries many ecclesiastics and monks wrote in Coptic.

In popular literature

The main character in the Hervey Allen novel Anthony Adverse, and the 1936 film of the same name, is an abandoned child who is placed in a foundling wheel on the saint's feast day, and given the name Anthony in his honor.

The novel The Einstein Prophecy by Robert Masello revolves around the recovery of Saint Anthony's ossuary during World War II. Much of the mythology surrounding Saint Anthony's time in the Sahara desert is used as the basis for the conflict the protagonists face after opening the ossuary.