Feastday: July 11

Patron: of students and Europe

Birth: 480

Death: 543

Canonized: Pope Honorius III in 1220

St. Benedict is believed to have been born around 480, as the son to a Roman noble of Norcia and the twin to his sister, Scholastica.

In the fifth century, the young Benedict was sent to Rome to finish his education with a nurse/housekeeper. The subject that dominated a young man's study then was rhetoric -- the art of persuasive speaking. A successful speaker was not one who had the best argument or conveyed the truth, but one who used rhythm, eloquence, and technique to convince. The power of the voice without foundation in the heart was the goal of the student's education. And that philosophy was reflected in the lives of the students as well. They had everything -- education, wealth, youth -- and they spent all of it in the pursuit of pleasure, not truth. Benedict watched in horror as vice unraveled the lives and ethics of his companions.

Afraid for his soul, Benedict fled Rome, gave up his inheritance and lived in a small village with his nurse. When God called him beyond this quiet life to an even deeper solitude, he went to the mountains of Subiaco. Although becoming a hermit was not his purpose in leaving, there he lived as a hermit under the direction of another hermit, Romanus.

One day, during his time living in a cave above a lake as a hermit, the Devil presented Benedict's imagination with a beautiful, tempting woman. Benedict resisted by rolling his body into a thorn bush until it was covered in scrapes. It is said through these body wounds, he cured the wounds of his soul.

After years of prayer, word of his holiness brought nearby monks to ask for his leadership. He warned them he would be too strict for them, but they insisted -- then tried to poison him when his warning proved true. The story goes, the monks attempted to poison Benedict's drink, but when he prayed a blessing over the cup - it shattered.

So Benedict was on his own again -- but not for long. The next set of followers were more sincere and he set up twelve monasteries in Subiaco where monks lived in separate communities of twelve.

He left these monasteries abruptly when the envious attacks of another hermit made it impossible to continue the spiritual leadership he had taken.

But it was in Monte Cassino he founded the monastery that became the roots of the Church's monastic system. Instead of founding small separate communities he gathered his disciples into one whole community. His own sister, Saint Scholastica, settled nearby to live a religious life.

After almost 1,500 years of monastic tradition his direction seems obvious to us. However, Benedict was an innovator. No one had ever set up communities like his before or directed them with a rule. What is part of history to us now was a bold, risky step into the future.

Benedict had the holiness and the ability to take this step. His beliefs and instructions on religious life were collected in what is now known as the Rule of Saint Benedict -- still directing religious life after 15 centuries.

In this tiny but powerful Rule, Benedict put what he had learned about the power of speaking and oratorical rhythms at the service of the Gospel. He did not drop out of school because he did not understand the subject! Scholars have told us that his Rule reflects an understanding of and skill with the rhetorical rules of the time. Despite his experience at school, he understood rhetoric was as much a tool as a hammer was. A hammer could be used to build a house or hit someone over the head. Rhetoric could be used to promote vice ... or promote God. Benedict did not shun rhetoric because it had been used to seduce people to vice; he reformed it.

Benedict did not want to lose the power of voice to reach up to God simply because others had use it to sink down to the gutter. He reminded us "Let us consider our place in sight of God and of his angels. Let us rise in chanting that our hearts and voices harmonize." There was always a voice reading aloud in his communities at meals, to receive guests, to educate novices. Hearing words one time was not enough -- "We wish this Rule to be read frequently to the community."

Benedict realized the strongest and truest foundation for the power of words was the Word of God itself: "For what page or word of the Bible is not a perfect rule for temporal life?" He had experienced the power of God's word as expressed in Scripture: "For just as from the heavens the rain and snow come down and do not return there till they have watered the earth, making it fertile and fruitful, giving seed to him who sows and bread to him who eats, so shall my word be that goes forth from my mouth; It shall not return to me void, but shall do my will, achieving the end for which I sent it" (Isaiah 55:10-11).

For prayer, Benedict turned to the psalms, the very songs and poems from the Jewish liturgy that Jesus himself had prayed. To join our voices with Jesus in praise of God during the day was so important that Benedict called it the "Work of God." And nothing was to be put before the work of God. "Immediately upon hearing the signal for the Divine Office all work will cease." Benedict believed with Jesus that "One does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes forth from the mouth of God' " (Matthew 4:4).

But it wasn't enough to just speak the words. Benedict instructed his followers to practice sacred reading -- the study of the very Scriptures they would be praying in the Work of God. In this lectio divina, he and his monks memorized the Scripture, studied it, and contemplated it until it became part of their being. Four to six hours were set aside each day for this sacred reading. If monks had free time it "should be used by the brothers to practice psalms." Lessons from Scripture were to be spoken from memory not read from a book. On Benedict's list of "Instruments of Good Works" is "to enjoy holy readings."

In one story of Benedict's life, a poor man came to the monastery begging for a little oil. Although Benedict commanded that the oil be given, the cellarer refused -- because there was only a tiny bit of oil left. If the cellarer gave any oil as alms there would be none for the monastery. Angry at this distrust of God's providence, Benedict knelt down to pray. As he prayed a bubbling sound came from inside the oil jar. The monks watched in fascination as oil from God filled the vessel so completely that it overflowed, leaked out beneath the lid and finally pushed the cover off, cascading out on to the floor.

In Benedictine prayer, our hearts are the vessel empty of thoughts and intellectual striving. All that remains is the trust in God's providence to fill us. Emptying ourselves this way brings God's abundant goodness bubbling up in our hearts, first with an inspiration or two, and finally overflowing our heart with contemplative love.

Benedict died on 21 March 543, not long after his sister. It is said he died with high fever on the very day God told him he would. He is the patron saint of Europe and students.

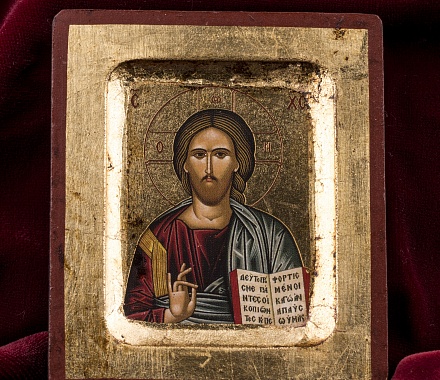

St. Benedict is often pictured with a bell, a broken tray, a raven, or a crosier. His feast day is celebrated on July 11.

"Saint Benedict" redirects here. For other uses, see Saint Benedict (disambiguation). Catholic saint and monk

Benedict of Nursia (Latin: Benedictus Nursiae; Italian: Benedetto da Norcia; Vulgar Latin: *Benedectos; Gothic: Benedikt; c. 2 March 480 – c. 21 March 547 AD) is a Christian saint venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, the Anglican Communion and Old Catholic Churches. He is a patron saint of Europe.

Benedict founded twelve communities for monks at Subiaco, Lazio, Italy (about 65 kilometres (40 mi) to the east of Rome), before moving to Monte Cassino in the mountains of southern Italy. The Order of Saint Benedict is of later origin and, moreover, not an "order" as commonly understood but merely a confederation of autonomous congregations.

Benedict's main achievement, his "Rule of Saint Benedict", contains a set of rules for his monks to follow. Heavily influenced by the writings of John Cassian, it shows strong affinity with the Rule of the Master, but it also has a unique spirit of balance, moderation and reasonableness (ἐπιείκεια, epieíkeia), which persuaded most Christian religious communities founded throughout the Middle Ages to adopt it. As a result, his Rule became one of the most influential religious rules in Western Christendom. For this reason, Giuseppe Carletti regarded Benedict as the founder of Western Christian monasticism.

Biography

Apart from a short poem attributed to Mark of Monte Cassino, the only ancient account of Benedict is found in the second volume of Pope Gregory I's four-book Dialogues, thought to have been written in 593, although the authenticity of this work has been disputed.

Gregory's account of Benedict's life is not, however, a biography in the modern sense of the word. It provides instead a spiritual portrait of the gentle, disciplined abbot. In a letter to Bishop Maximilian of Syracuse, Gregory states his intention for his Dialogues, saying they are a kind of floretum (an anthology, literally, 'flowers') of the most striking miracles of Italian holy men.

Gregory did not set out to write a chronological, historically anchored story of Benedict, but he did base his anecdotes on direct testimony. To establish his authority, Gregory explains that his information came from what he considered the best sources: a handful of Benedict's disciples who lived with him and witnessed his various miracles. These followers, he says, are Constantinus, who succeeded Benedict as Abbot of Monte Cassino, Honoratus, who was abbot of Subiaco when St Gregory wrote his Dialogues, Valentinianus, and Simplicius.

In Gregory's day, history was not recognised as an independent field of study; it was a branch of grammar or rhetoric, and historia was an account that summed up the findings of the learned when they wrote what was, at that time, considered 'history.' Gregory's Dialogues Book Two, then, an authentic medieval hagiography cast as a conversation between the Pope and his deacon Peter, is designed to teach spiritual lessons.

Early life

He was the son of a Roman noble of Nursia, the modern Norcia, in Umbria. A tradition which Bede accepts makes him a twin with his sister Scholastica. If 480 is accepted as the year of his birth, the year of his abandonment of his studies and leaving home would be about 500. Gregory's narrative makes it impossible to suppose him younger than 20 at the time.

Benedict was sent to Rome to study, but was disappointed by the life he found there. He does not seem to have left Rome for the purpose of becoming a hermit, but only to find some place away from the life of the great city. He took his old nurse with him as a servant and they settled down to live in Enfide. Enfide, which the tradition of Subiaco identifies with the modern Affile, is in the Simbruini mountains, about forty miles from Rome and two miles from Subiaco.

Saint Benedict orders Saint Maurus to the rescue of Saint Placidus, by Fra Filippo Lippi, 1445 A.D.

Saint Benedict orders Saint Maurus to the rescue of Saint Placidus, by Fra Filippo Lippi, 1445 A.D.

A short distance from Enfide is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains and leading directly to Subiaco. The path continues to ascend, and the side of the ravine, on which it runs, becomes steeper, until a cave is reached above which the mountain now rises almost perpendicularly; while on the right, it strikes in a rapid descent down to where, in Benedict's day, 500 feet (150 m) below, lay the blue waters of the lake. The cave has a large triangular-shaped opening and is about ten feet deep. On his way from Enfide, Benedict met a monk, Romanus of Subiaco, whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus had discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to Subiaco, and had given him the monk's habit. By his advice Benedict became a hermit and for three years, unknown to men, lived in this cave above the lake.

Later life

Gregory tells us little of these years. He now speaks of Benedict no longer as a youth (puer), but as a man (vir) of God. Romanus, Gregory tells us, served Benedict in every way he could. The monk apparently visited him frequently, and on fixed days brought him food.

During these three years of solitude, broken only by occasional communications with the outer world and by the visits of Romanus, Benedict matured both in mind and character, in knowledge of himself and of his fellow-man, and at the same time he became not merely known to, but secured the respect of, those about him; so much so that on the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighbourhood (identified by some with Vicovaro), the community came to him and begged him to become its abbot. Benedict was acquainted with the life and discipline of the monastery, and knew that "their manners were diverse from his and therefore that they would never agree together: yet, at length, overcome with their entreaty, he gave his consent" (ibid., 3). The experiment failed; the monks tried to poison him. The legend goes that they first tried to poison his drink. He prayed a blessing over the cup and the cup shattered. Thus he left the group and went back to his cave at Subiaco. There lived in the neighborhood a priest called Florentius who, moved by envy, tried to ruin him. He tried to poison him with poisoned bread. When he prayed a blessing over the bread, a raven swept in and took the loaf away. From this time his miracles seem to have become frequent, and many people, attracted by his sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to be under his guidance. Having failed by sending him poisonous bread, Florentius tried to seduce his monks with some prostitutes. To avoid further temptations, in about 530 Benedict left Subiaco. He founded 12 monasteries in the vicinity of Subiaco, and, eventually, in 530 he founded the great Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, which lies on a hilltop between Rome and Naples.

During the invasion of Italy, Totila, King of the Goths, ordered a general to wear his kingly robes and to see whether Benedict would discover the truth. Immediately Benedict detected the impersonation, and Totila came to pay him due respect.

Veneration

Totila and Saint Benedict, painted by Spinello Aretino

Totila and Saint Benedict, painted by Spinello Aretino

He is believed to have died of a fever at Monte Cassino not long after his twin sister, Scholastica, and was buried in the same place as his sister. According to tradition, this occurred on 21 March 547. He was named patron protector of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964. In 1980, Pope John Paul II declared him co-patron of Europe, together with Cyril and Methodius. Furthermore, he is the patron saint of speleologists.

In the pre-1970 General Roman Calendar, his feast is kept on 21 March, the day of his death according to some manuscripts of the Martyrologium Hieronymianum and that of Bede. Because on that date his liturgical memorial would always be impeded by the observance of Lent, the 1969 revision of the General Roman Calendar moved his memorial to 11 July, the date that appears in some Gallic liturgical books of the end of the 8th century as the feast commemorating his birth (Natalis S. Benedicti). There is some uncertainty about the origin of this feast. Accordingly, on 21 March the Roman Martyrology mentions in a line and a half that it is Benedict's day of death and that his memorial is celebrated on 11 July, while on 11 July it devotes seven lines to speaking of him, and mentions the tradition that he died on 21 March.

The Eastern Orthodox Church commemorates Saint Benedict on 14 March.

The Anglican Communion has no single universal calendar, but a provincial calendar of saints is published in each province. In almost all of these, Saint Benedict is commemorated on 11 July.

Benedict is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 11 July.

Rule of Saint Benedict

Main article: Rule of Saint BenedictBenedict wrote the Rule in 516 for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot. The Rule comprises seventy-three short chapters. Its wisdom is twofold: spiritual (how to live a Christocentric life on earth) and administrative (how to run a monastery efficiently). More than half of the chapters describe how to be obedient and humble, and what to do when a member of the community is not. About one-fourth regulate the work of God (the "opus Dei"). One-tenth outline how, and by whom, the monastery should be managed.

Following the golden rule of Ora et Labora - pray and work, the monks each day devoted eight hours to prayer, eight hours to sleep, and eight hours to manual work, sacred reading and/or works of charity.

Saint Benedict Medal

Main article: Saint Benedict Medal Image of Saint Benedict with a cross (which is inscribed, "Crux sacra sit mihi lux! Non-draco sit mihi dux!" ("May the holy cross be my light! May the dragon never be my guide!")) and a scroll stating "Vade retro Satana! Nunquam suade mihi vana! Sunt mala quae libas. Ipse venena bibas! ("Begone Satan! Never tempt me with your vanities! The drink you offer is evil. Drink that poison yourself!", or in brief,Vade Retro Satana which is abbreviated on the Saint Benedict Medal.

Image of Saint Benedict with a cross (which is inscribed, "Crux sacra sit mihi lux! Non-draco sit mihi dux!" ("May the holy cross be my light! May the dragon never be my guide!")) and a scroll stating "Vade retro Satana! Nunquam suade mihi vana! Sunt mala quae libas. Ipse venena bibas! ("Begone Satan! Never tempt me with your vanities! The drink you offer is evil. Drink that poison yourself!", or in brief,Vade Retro Satana which is abbreviated on the Saint Benedict Medal.

This devotional medal originally came from a cross in honor of Saint Benedict. On one side, the medal has an image of Saint Benedict, holding the Holy Rule in his left hand and a cross in his right. There is a raven on one side of him, with a cup on the other side of him. Around the medal's outer margin are the words "Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur" ("May we be strengthened by his presence in the hour of our death"). The other side of the medal has a cross with the initials CSSML on the vertical bar which signify "Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux" ("May the Holy Cross be my light") and on the horizontal bar are the initials NDSMD which stand for "Non-Draco Sit Mihi Dux" ("Let not the dragon be my guide"). The initials CSPB stand for "Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti" ("The Cross of the Holy Father Benedict") and are located on the interior angles of the cross. Either the inscription "PAX" (Peace) or the Christogram "IHS" may be found at the top of the cross in most cases. Around the medal's margin on this side are the Vade Retro Satana initials VRSNSMV which stand for "Vade Retro Satana, Nonquam Suade Mihi Vana" ("Begone Satan, do not suggest to me thy vanities") then a space followed by the initials SMQLIVB which signify "Sunt Mala Quae Libas, Ipse Venena Bibas" ("Evil are the things thou profferest, drink thou thy own poison").

Benedict depicted on a Jubilee Saint Benedict Medal for the 1,400th anniversary of his birth in 1880

Benedict depicted on a Jubilee Saint Benedict Medal for the 1,400th anniversary of his birth in 1880

This medal was first struck in 1880 to commemorate the fourteenth centenary of Benedict's birth and is also called the Jubilee Medal; its exact origin, however, is unknown. In 1647, during a witchcraft trial at Natternberg near Metten Abbey in Bavaria, the accused women testified they had no power over Metten, which was under the protection of the cross. An investigation found a number of painted crosses on the walls of the abbey with the letters now found on St Benedict medals, but their meaning had been forgotten. A manuscript written in 1415 was eventually found that had a picture of Benedict holding a scroll in one hand and a staff which ended in a cross in the other. On the scroll and staff were written the full words of the initials contained on the crosses. Medals then began to be struck in Germany, which then spread throughout Europe. This medal was first approved by Pope Benedict XIV in his briefs of 23 December 1741 and 12 March 1742.

Benedict has been also the motive of many collector's coins around the world. The Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders', issued on 13 March 2002 is one of them.

Influence

Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders' commemorative coin

Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders' commemorative coin

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

Aquinas, Scotus, and Ockham Aquinas, Scotus, and Ockham |

| Ethics |

|

| Schools |

|

| Philosophers |

Ancient

|

Postclassical

|

Modern

|

Contemporary

|

|

|

|

The early Middle Ages have been called "the Benedictine centuries." In April 2008, Pope Benedict XVI discussed the influence St Benedict had on Western Europe. The pope said that "with his life and work St Benedict exercised a fundamental influence on the development of European civilization and culture" and helped Europe to emerge from the "dark night of history" that followed the fall of the Roman empire.

Benedict contributed more than anyone else to the rise of monasticism in the West. His Rule was the foundational document for thousands of religious communities in the Middle Ages. To this day, The Rule of St. Benedict is the most common and influential Rule used by monasteries and monks, more than 1,400 years after its writing. Today the Benedictine family is represented by two branches: the Benedictine Federation and the Cistercians.

A basilica was built upon the birthplace of Benedict and Scholastica in the 1400s. Ruins of their familial home were excavated from beneath the church and preserved. The earthquake of 30 October 2016 completely devastated the structure of the basilica, leaving only the front facade and altar standing.

Gallery

- See also Category:Paintings of Benedict of Nursia.

-

Saint Benedict and the cup of poison (Melk Abbey, Austria)

-

Small gold-coloured Saint Benedict crucifix

-

Both sides of a Saint Benedict Medal

-

Portrait (1926) by Herman Nieg (1849–1928); Heiligenkreuz Abbey, Austria

-

St. Benedict at the Death of St. Scholastica (c. 1250–60), Musée National de l'Age Médiévale, Paris, orig. at the Abbatiale of St. Denis

-

Statue in Einsiedeln, Switzerland