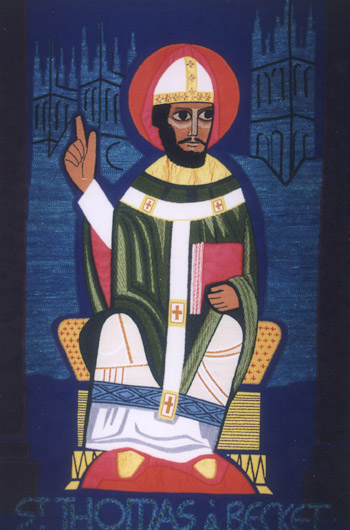

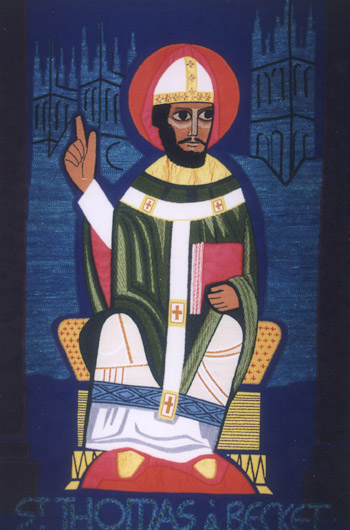

Feastday: December 29There is a romantic legend that the mother of Thomas Becket was a Saracen princess who followed his father, a pilgrim or crusader, back from the Holy Land, and wandered about Europe repeating the only English words she knew, "London" and "Becket," until she found him. There is no foundation for the story. According to a contemporary writer, Thomas Becket was the son of Gilbert Becket, sheriff of London; another relates that both parents were of Norman blood. Whatever his parentage, we know with certainty that the future chancellor and archbishop of Canterbury was born on St. Thomas day, 1118, of a good family, and that he was educated at a school of canons regular at Merton Priory in Sussex, and later at the University of Paris. When Thomas returned from France, his parents had died. Obliged to make his way unaided, he obtained an appointment as clerk to the sheriff's court, where he showed great ability. All accounts describe him as a strongly built, spirited youth, a lover of field sports, who seems to have spent his leisure time in hawking and hunting. One day when he was out hunting with his falcon, the bird swooped down at a duck, and as the duck dived, plunged after it into the river. Thomas himself leapt in to save the valuable hawk, and the rapid stream swept him along to a mill, where only the accidental stopping of the wheel saved his life. The episode serves to illustrate the impetuous daring which characterized Becket all through his life.

Birth: 1118

Death: 1170

At the age of twenty-four Thomas was given a post in the household of Theobald, archbishop of Canterbury, and while there he apparently resolved on a career in the Church, for he took minor orders. To prepare himself further, he obtained the archbishop's permission to study canon law at the University of Bologna, continuing his studies at Auxerre, France. On coming back to England, he became provost of Beverley, and canon at Lincoln and St. Paul's cathedrals. His ordination as deacon occurred in 1154. Theobald appointed him archdeacon of Canterbury, the highest ecclesiastical office in England after a bishopric or an abbacy, and began to entrust him with the most intricate affairs; several times he was sent on important missions to Rome. It was Thomas' diplomacy that dissuaded Pope Eugenius III from sanctioning the coronation of Eustace, eldest son of Stephen, and when Henry of Anjou, great grandson of William the Conqueror, asserted his claim to the English crown and became King Henry II, it was not long before he appointed this gifted churchman as chancellor, that is, chief minister. An old chronicle describes Thomas as "slim of growth, and pale of hue, with dark hair, a long nose, and a straightly featured face.

Blithe of countenance was he, winning and lovable in conversation, frank of speech in his discourses but slightly stuttering in his talk, so keen of discernment that he could always make difficult questions plain after a wise manner." Thomas discharged his duties as chancellor conscientiously and well.

Like the later chancellor of the realm, Thomas Moore, who also became a martyr and a saint, Thomas Becket was the close personal friend as well as the loyal servant of his young sovereign. They were said to have one heart and one mind between them, and it seems possible that to Becket's influence were due, in part, those reforms for which Henry is justly praised, that is, his measures to secure equitable dealing for all his subjects by a more uniform and efficient system of law. But it was not only their common interest in matters of state that bound them together. They were also boon companions and spent merry hours together. It was almost the only relaxation Thomas allowed himself, for he was an ambitious man. He had a taste for magnificence, and his household was as fine--if not finer--than the King's. When he was sent to France to negotiate a royal marriage, he took a personal retinue of two hundred men, with a train of several hundred more, knights and squires, clerics and servants, eight fine wagons, music and singers, hawks and hounds, monkeys and mastiffs. Little wonder that the French gaped in wonder and asked, "If this is the chancellor's state, what can the King's be like?" His entertainments, his gifts, and his liberality to the poor were also on a very lavish scale.

In 1159 King Henry raised an army of mercenaries in France to regain the province of Toulouse, a part of the inheritance of his wife, the famous Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Thomas served Henry in this war with a company of seven hundred knights of his own. Wearing armor like any other fighting man, he led assaults and engaged in single combat. Another churchman, meeting him, exclaimed: "What do you mean by wearing such a dress? You look more like a falconer than a cleric. Yet you are a cleric in person, and many times over in office-archdeacon of Canterbury, dean of Hastings, provost of Beverley, canon of this church and that, procurator of the archbishop, and like to be archbishop, too, the rumor goes!" Thomas received the rebuke with good humor.

Although he was proud, strong-willed, and irascible, and remained so all his life, he did not neglect to make seasonal retreats at Merton and took the discipline imposed on him there. His confessor during this time testified later to the blamelessness of his private life, under conditions of extreme temptation. If he sometimes went too far in those schemes of the King which tended to infringe on the ancient prerogatives and rights of the Church, at other times he opposed Henry with vigor.

In 1161 Archbishop Theobald died. King Henry was then in Normandy with Thomas, whom he resolved to make the next primate of England. When Henry announced his intention, Thomas, demurring, told him: "Should God permit me to be the archbishop of Canterbury, I would soon lose your Majesty's favor, and the affection with which you honor me would be changed into hatred. For there are several things you do now in prejudice of the rights of the Church which make me fear you would require of me what I could not agree to; and envious persons would not fail to make it the occasion of endless strife between us." The King paid no heed to this remonstrance, and sent bishops and noblemen to the monks of Canterbury, ordering them to labor with the same zeal to set his chancellor in the see as they would to set the crown on the young prince's head. Thomas continued to refuse the promotion until the legate of the Holy See, Cardinal Henry of Pisa, overrode his scruples. The election took place in May, 1162. Young Prince Henry, then in London, gave the necessary consent in his father's name. Thomas, now forty-four years old, rode to Canterbury and was first ordained priest by Walter, bishop of Rochester, and then on the octave of Pentecost was consecrated archbishop by the bishop of Winchester. Shortly afterwards he received the pallium sent by Pope Alexander III.

From this day worldly grandeur no longer marked Thomas' way of life. Next his skin he wore a hairshirt, and his customary dress was a plain black cassock, a linen surplice, and a sacerdotal stole about his neck. He lived ascetically, spent much time in the distribution of alms, in reading and discussing the Scriptures with Herbert of Bosham, in visiting the infirmary, and supervising the monks at their work. He took special care in selecting candidates for Holy Orders. As ecclesiastical judge, he was rigorously just.

Although as archbishop Thomas had resigned the chancellorship, against the King's wish, the relations between the two men seemed to be unchanged for a time. But a host of troubles was brewing, and the crux of all of them was the relationship between Church and state. In the past the landowners, among which the Church was one of the largest, for each hide [1] of land they held, had paid annually two shillings to the King's officers, who in return undertook to protect them from the rapacity of minor tax- gatherers. This was actually a flagrant form of graft and the King now ordered the money paid into his own exchequer. The archbishop protested, and there were hot words between him and the King. Thenceforth the King's demands were directed solely against the clergy, with no mention of other landholders who were equally involved.

Then came the affair of Philip de Brois, a canon accused of murdering a soldier.

According to a long-established law, as a cleric he was tried in an ecclesiastical court, where he was acquitted by the judge, the bishop of Lincoln, but ordered to pay a fine to the deceased man's relations. A king's justice then made an effort to bring him before his civil court, but he could not be tried again upon that indictment and told the king's justice so in insulting terms. Thereat Henry ordered him tried again both for the original murder charge--and for his later misdemeanor. Thomas now pressed to have the case referred to his own archiepiscopal court; the King reluctantly agreed, and appointed both lay and clerical assessors. Philip's plea of a previous acquittal was accepted as far as the murder was concerned, but he was punished for his contempt of a royal court. The King thought the sentence too mild and remained dissatisfied. In October, 1163, the King called the bishops of his realm to a council at Westminster, at which he demanded their assent to an edict that thenceforth clergy proved guilty of crimes against the civil law should be handed over to the civil courts for punishment.

Thomas stiffened the bishops against yielding. But finally, at the council of Westminster they assented reluctantly to the instrument known as the Constitutions of Clarendon, which embodied the royal "customs" in Church matters, and including some additional points, making sixteen in all. It was a revolutionary document: it provided that no prelate should leave the kingdom without royal permission, which would serve to prevent appeals to the Pope; that no tenant-in-chief should be excommunicated against the King's will; that the royal court was to decide in which court clerics accused of civil offenses should be tried; that the custody of vacant Church benefices and their revenues should go to the King. Other provisions were equally damaging to the authority and prestige of the Church. The bishops gave their assent only with a reservation, "saving their order," which was tantamount to a refusal.

Thomas was now full of remorse for having weakened, thus setting a bad example to the bishops, but at the same time he did not wish to widen the breach between himself and the King. He made a futile effort to cross the Channel and put the case before the Pope. On his part, the King was bent on vengeance for what he considered the disloyalty and ingratitude of the archbishop. He ordered Thomas to give up certain castles and honors which he held from him, and began a campaign to persecute and discredit him. Various charges of chicanery and financial dishonesty were brought against Thomas, dating from the time he was chancellor. The bishop of Winchester pleaded the archbishop's discharge. The plea was disallowed; Thomas offered a voluntary payment of his own money, and that was refused.

The affair was building up to a crisis, when, on October 13, 1164, the King called another great council at Northampton. Thomas went, after celebrating Mass, carrying his archbishop's cross in his hand. The Earl of Leicester came out with a message from the King: "The King commands you to render your accounts. Otherwise you must hear his judgment." "Judgment?" exclaimed Thomas. "I was given the church of Canterbury free from temporal obligations. I am therefore not liable and will not plead with regard to them. Neither law nor reason allows children to judge and condemn their fathers.

Wherefore I refuse the King's judgment and yours and everyone's. Under God, I will be judged by the Pope alone."

Determined to stand out against the King, Thomas left Northampton that night, and soon thereafter embarked secretly for Flanders. Louis VII, King of France, invited Thomas into his dominions. Meanwhile King Henry forbade anyone to give him aid.

Gilbert, abbot of Sempringham, was accused of having sent him some relief. Although the abbot had done nothing, he refused to swear he had not, because, he said, it would have been a good deed and he would say nothing that might seem to brand it as a criminal act. Henry quickly dispatched several bishops and others to put his case before Pope Alexander, who was then at Sens. Thomas also presented himself to the Pope and showed him the Constitutions of Clarendon, some of which Alexander pronounced intolerable, others impossible. He rebuked Thomas for ever having considered accepting them. The next day Thomas confessed that he had, though unwillingly, received the see of Canterbury by an election somewhat irregular and uncanonical, and had acquitted himself badly in it. He resigned his office, returned the episcopal ring to the Pope, and withdrew. After deliberation, the Pope called him back and reinstated him, with orders not to abandon his office, for to do so would be to abandon the cause of God. He then recommended Thomas to the Cistercian abbot at Pontigny.

Thomas then put on a monk's habit, and submitted himself to the strict rule of the monastery. Over in England King Henry was busy confiscating the goods of all the friends, relations, and servants of the archbishop, and banishing them, first binding them by oath to go to Thomas at Pontigny, that the sight of their distress might move him. Troops of these exiles soon appeared at the abbey. Then Henry notified the Cistercians that if they continued to harbor his enemy he would sequestrate all their houses in his dominions. After this, the abbot hinted that Thomas was no longer welcome in his abbey. The archbishop found refuge as the guest of King Louis at the royal abbey of St. Columba, near Sens.

This historic quarrel dragged on for three years. Thomas was named by the Pope as his legate for all England except York, whereupon Thomas excommunicated several of his adversaries; yet at times he showed himself conciliatory towards the King. The French king was also drawn into the struggle, and the two kings had a conference in 1169 at Montmirail. King Louis was inclined to take Thomas' side. A reconciliation was finally effected between Thomas and Henry, although the lines of power were not too clearly drawn. The archbishop now made preparations to return to his see. With a premonition of his fate, he remarked to the bishop of Paris in parting, "I am going to England to die." On December 1, 1172, he disembarked at Sandwich, and on the journey to Canterbury the way was lined with cheering people, welcoming him home. As he rode into the cathedral city at the head of a triumphal procession, every bell was ringing. Yet in spite of the public demonstration, there was an atmosphere of foreboding.

At the reconciliation in France, Henry had agreed to the punishment of Roger, archbishop of York, and the bishops of London and Salisbury, who had assisted at the coronation of Henry's son, despite the long-established right of the archbishop of Canterbury to perform this ceremony and in defiance of the Pope's explicit instructions. It had been another attempt to lower the prestige of the primate's see. Thomas had sent on in advance of his return the papal letters suspending Roger and confirming the excommunication of the two bishops involved. On the eve of his arrival a deputation waited on him to ask for the withdrawal of these sentences. He agreed on condition that the three would swear thenceforth to obey the Pope. This they refused to do, and together went to rejoin King Henry, who was visiting his domains in France.

At Canterbury Thomas was subjected to insult by one Ranulf de Broc, from whom he had demanded the restoration of Saltwood Castle, a manor previously belonging to the archbishop's see. After a week's stay there he went up to London, where Henry's son, "the young King," refused to see him. He arrived back in Canterbury on or about his fifty-second birthday. Meanwhile the three bishops had laid their complaints before the King at Bur, near Bayeux, and someone had exclaimed aloud that there would be no peace for the realm while Becket lived. At this, the King, in a fit of rage, pronounced some words which several of his hearers took as a rebuke to them for allowing Becket to continue to live and thereby disturb him. Four of his knights at once set off for England and made their way to the irate family at Saltwood. Their names were Reginald Fitzurse, William de Tracy, Hugh de Morville, and Richard le Bret.

On St. John's day Thomas received a letter warning him of danger, and all southeast Kent was in a state of ferment. On the afternoon of December 29, the four knights came to see him in his episcopal palace. During the interview they made several demands, in particular that Thomas remove the censures on the three bishops. The knights withdrew, uttering threats and oaths. A few minutes later there were loud outcries, a shattering of doors and clashing of arms, and the archbishop, urged on by his attendants, began moving slowly through the cloister passage to the cathedral. It was now twilight and vespers were being sung. At the door of the north transept he was met by some terrified monks, whom he commanded to get back to the choir. They withdrew a little and he entered the church, but the knights were seen behind him in the dim light. The monks slammed the door on them and bolted it. In their confusion they shut out several of their own brethren, who began beating loudly on the door.

Becket turned and cried, "Away, you cowards ! A church is not a castle." He reopened the door himself, then went towards the choir, accompanied by Robert de Merton, his aged teacher and confessor, William Fitzstephen, a cleric in his household, and a monk, Edward Grim. The others fled to the crypt and other hiding places, and Grim alone remained. At this point the knights broke in shouting, "Where is Thomas the traitor?" "Where is the archbishop?" "Here I am," he replied, "no traitor, but archbishop and priest of God!" He came down the steps to stand between the altars of Our Lady and St. Benedict.

The knights clamored at him to absolve the bishops, and Thomas answered firmly, "I cannot do other than I have done. Reginald, you have received many favors from me.

Why do you come into my church armed?" Fitzurse made a threatening gesture with his axe. "I am ready to die," said Thomas, "but God's curse on you if you harm my people." There was some scuffling as they tried to carry Thomas outside bodily.

Fitzurse flung down his axe and drew his sword. "You pander, you owe me fealty and submission!" exclaimed the archbishop. Fitzurse shouted back, "I owe no fealty contrary to the King ! " and knocked off Thomas' cap. At this, Thomas covered his face and called aloud on God and the saints. Tracy struck a blow, which Grim intercepted with his own arm, but it grazed Thomas' skull and blood ran down into his eyes. He wiped the stain away and cried, "Into Thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit!" Another blow from Tracy beat him to his knees, and he pitched forward onto his face, murmuring, "For the name of Jesus and in defense of the Church I am willing to die." With a vigorous thrust Le Bret struck deep into his head, breaking his sword against the pavement, and Hugh of Horsea added a blow, although the archbishop was now dying. Hugh de Morville stood by but struck no blow. The murderers, brandishing their swords, now dashed away through the cloisters, shouting "The King's men! The King's men!" The cathedral itself was filling with people unaware of the catastrophe, and a thunderstorm was breaking overhead.[2] The archbishop's body lay in the middle of the transept, and for a time no one dared approach it. A deed of such sacrilege was bound to be regarded with horror and indignation. When the news was brought to the King, he shut himself up and fasted for forty days, for he knew that his chance remark had sped the courtiers to England bent on vengeance. He later performed public penance in Canterbury Cathedral and in 1172 received absolution from the papal delegates.

Within three years of his death the archbishop had been canonized as a martyr. Though far from a faultless character, Thomas Becket, when his time of testing came, had the courage to lay down his life to defend the ancient rights of the Church against an aggressive state. The discovery of his hairshirt and other evidences of austerity, and the many miracles which were reported at his tomb, increased the veneration in which he was held. The shrine of the "holy blessed martyr," as Chaucer called him, soon became famous, and the old Roman road running from London to Canterbury known as "Pilgrim's Way." His tomb was magnificently adorned with gold, silver, and jewels, only to be despoiled by Henry VIII; the fate of his relics is uncertain. They may have been destroyed as a part of Henry's policy to subordinate the English Church to the civil authority. Mementoes of this saint are preserved at the cathedral of Sens. The feast of St. Thomas of Canterbury is now kept throughout the Roman Catholic Church, and in England he is regarded as the protector of the secular clergy.

To all our readers, Please don't scroll past this.

Today, we humbly ask you to defend Catholic Online's independence. 98% of our readers don't give; they simply look the other way. If you donate just $5.00, or whatever you can, Catholic Online could keep thriving for years. Most people donate because Catholic Online is useful. If Catholic Online has given you $5.00 worth of knowledge this year, take a minute to donate. Show the volunteers who bring you reliable, Catholic information that their work matters. If you are one of our rare donors, you have our gratitude and we warmly thank you. Help Now > 12th-century Archbishop of Canterbury, Chancellor of England and saint "Thomas a Becket" redirects here. For other uses, see Thomas a Becket (disambiguation) and Thomas Beckett.

Attributed arms of Saint Thomas Becket: Argent, three Cornish choughs proper, visible in many English churches dedicated to him. As he died 30 to 45 years before the age of heraldry, he bore no arms.

Attributed arms of Saint Thomas Becket: Argent, three Cornish choughs proper, visible in many English churches dedicated to him. As he died 30 to 45 years before the age of heraldry, he bore no arms.

Thomas Becket (/ˈbɛkɪt/), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his murder in 1170. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by both the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion. He engaged in conflict with Henry II, King of England, over the rights and privileges of the Church and was murdered by followers of the king in Canterbury Cathedral. Soon after his death, he was canonised by Pope Alexander III.

Sources

The main sources for the life of Becket are a number of biographies written by contemporaries. A few of these documents are by unknown writers, although traditional historiography has given them names. The known biographers are John of Salisbury, Edward Grim, Benedict of Peterborough, William of Canterbury, William fitzStephen, Guernes of Pont-Sainte-Maxence, Robert of Cricklade, Alan of Tewkesbury, Benet of St Albans, and Herbert of Bosham. The other biographers, who remain anonymous, are generally given the pseudonyms of Anonymous I, Anonymous II (or Anonymous of Lambeth), and Anonymous III (or Lansdowne Anonymous). Besides these accounts, there are also two other accounts that are likely contemporary that appear in the Quadrilogus II and the Thómas saga erkibyskups. Besides these biographies, there is also the mention of the events of Becket's life in the chroniclers of the time. These include Robert of Torigni's work, Roger of Howden's Gesta Regis Henrici Secundi and Chronica, Ralph Diceto's works, William of Newburgh's Historia Rerum, and Gervase of Canterbury's works.

Early life

Becket was born about 1119, or in 1120 according to later tradition. He was born on Cheapside, London, on 21 December, which was the feast day of St Thomas the Apostle. He was the son of Gilbert and Matilda Beket [sic]. Gilbert's father was from Thierville in the lordship of Brionne in Normandy, and was either a small landowner or a petty knight. Matilda was also of Norman descent, and her family may have originated near Caen. Gilbert was perhaps related to Theobald of Bec, whose family also was from Thierville. Gilbert began his life as a merchant, perhaps in textiles, but by the 1120s he was living in London and was a property owner, living on the rental income from his properties. He also served as the sheriff of the city at some point. They were buried in Old St Paul's Cathedral.

Plaque marking Becket's birthplace along Cheapside

Plaque marking Becket's birthplace along Cheapside

One of Becket's father's wealthy friends, Richer de L'Aigle, often invited Thomas to his estates in Sussex where Becket was exposed to hunting and hawking. According to Grim, Becket learned much from Richer, who was later a signatory of the Constitutions of Clarendon against Thomas.

Beginning when he was 10, Becket was sent as a student to Merton Priory southwest of the city in Surrey and later attended a grammar school in London, perhaps the one at St Paul's Cathedral. He did not study any subjects beyond the trivium and quadrivium at these schools. Later, he spent about a year in Paris around age 20. He did not, however, study canon or civil law at this time and his Latin skill always remained somewhat rudimentary. Some time after Becket began his schooling, Gilbert Beket suffered financial reverses, and the younger Becket was forced to earn a living as a clerk. Gilbert first secured a place for his son in the business of a relative—Osbert Huitdeniers—and then later Becket acquired a position in the household of Theobald of Bec, by now the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Theobald entrusted him with several important missions to Rome and also sent him to Bologna and Auxerre to study canon law. In 1154, Theobald named Becket Archdeacon of Canterbury, and other ecclesiastical offices included a number of benefices, prebends at Lincoln Cathedral and St Paul's Cathedral, and the office of Provost of Beverley. His efficiency in those posts led to Theobald recommending him to King Henry II for the vacant post of Lord Chancellor, to which Becket was appointed in January 1155.

As Chancellor, Becket enforced the king's traditional sources of revenue that were exacted from all landowners, including churches and bishoprics. King Henry sent his son Henry to live in Becket's household, it being the custom then for noble children to be fostered out to other noble houses.

Primacy

Becket was nominated as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162, several months after the death of Theobald. His election was confirmed on 23 May 1162 by a royal council of bishops and noblemen. Henry may have hoped that Becket would continue to put the royal government first, rather than the church. However, the famous transformation of Becket into an ascetic occurred at this time.

- Becket enthroned as Archbishop of Canterbury from a Nottingham Alabaster in the Victoria & Albert Museum

-

-

-

Becket was ordained a priest on 2 June 1162 at Canterbury, and on 3 June 1162 was consecrated as archbishop by Henry of Blois, the Bishop of Winchester and the other suffragan bishops of Canterbury.

A rift grew between Henry and Becket as the new archbishop resigned his chancellorship and sought to recover and extend the rights of the archbishopric. This led to a series of conflicts with the King, including that over the jurisdiction of secular courts over English clergymen, which accelerated antipathy between Becket and the king. Attempts by Henry to influence the other bishops against Becket began in Westminster in October 1163, where the King sought approval of the traditional rights of the royal government in regard to the church. This led to the Constitutions of Clarendon, where Becket was officially asked to agree to the King's rights or face political repercussions.

Constitutions of Clarendon

Main article: Becket controversy Further information: Constitutions of Clarendon 14th-century depiction of Becket with King Henry II

14th-century depiction of Becket with King Henry II

King Henry II presided over the assemblies of most of the higher English clergy at Clarendon Palace on 30 January 1164. In sixteen constitutions, he sought less clerical independence and a weaker connection with Rome. He employed all his skills to induce their consent and was apparently successful with all but Becket. Finally, even Becket expressed his willingness to agree to the substance of the Constitutions of Clarendon, but he still refused to formally sign the documents. Henry summoned Becket to appear before a great council at Northampton Castle on 8 October 1164, to answer allegations of contempt of royal authority and malfeasance in the Chancellor's office. Convicted on the charges, Becket stormed out of the trial and fled to the Continent.

Henry pursued the fugitive archbishop with a series of edicts, targeting Becket as well as all of Becket's friends and supporters, but King Louis VII of France offered Becket protection. He spent nearly two years in the Cistercian abbey of Pontigny, until Henry's threats against the order obliged him to return to Sens. Becket fought back by threatening excommunication and interdict against the king and bishops and the kingdom, but Pope Alexander III, though sympathising with him in theory, favoured a more diplomatic approach. Papal legates were sent in 1167 with authority to act as arbitrators.

A Seal of the Abbot of Arbroath, showing the murder of Becket. Arbroath Abbey was founded 8 years after the death of St Thomas and dedicated to him; it became the wealthiest abbey in Scotland.

A Seal of the Abbot of Arbroath, showing the murder of Becket. Arbroath Abbey was founded 8 years after the death of St Thomas and dedicated to him; it became the wealthiest abbey in Scotland.

In 1170, Alexander sent delegates to impose a solution to the dispute. At that point, Henry offered a compromise that would allow Thomas to return to England from exile.

Assassination

Becket's assassination and funeral, from a French enamelled chasse made about 1190–1200, one of about 52 surviving examples.

Becket's assassination and funeral, from a French enamelled chasse made about 1190–1200, one of about 52 surviving examples.

Sculpture and altar marking the spot of Thomas Becket's martyrdom, Canterbury Cathedral. The sculpture by Giles Blomfeld represents the knights' four swords (two metal swords with reddened tips and their two shadows).

Sculpture and altar marking the spot of Thomas Becket's martyrdom, Canterbury Cathedral. The sculpture by Giles Blomfeld represents the knights' four swords (two metal swords with reddened tips and their two shadows).

In June 1170, Roger de Pont L'Évêque, the archbishop of York, along with Gilbert Foliot, the Bishop of London, and Josceline de Bohon, the Bishop of Salisbury, crowned the heir apparent, Henry the Young King, at York. This was a breach of Canterbury's privilege of coronation, and in November 1170 Becket excommunicated all three.

Upon hearing reports of Becket's actions, Henry is said to have uttered words that were interpreted by his men as wishing Becket killed. The king's exact words are in doubt and several versions have been reported. The most commonly quoted, as handed down by oral tradition, is "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?", but according to historian Simon Schama this is incorrect: he accepts the account of the contemporary biographer Edward Grim, writing in Latin, who gives us "What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?" Many variations have found their way into popular culture.

Whatever Henry said, it was interpreted as a royal command, and four knights, Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy and Richard le Breton, set out to confront the Archbishop of Canterbury.

On 29 December 1170, they arrived at Canterbury. According to accounts left by the monk Gervase of Canterbury and eyewitness Edward Grim, they placed their weapons under a tree outside the cathedral and hid their mail armour under cloaks before entering to challenge Becket. The knights informed Becket he was to go to Winchester to give an account of his actions, but Becket refused. It was not until Becket refused their demands to submit to the king's will that they retrieved their weapons and rushed back inside for the killing. Becket, meanwhile, proceeded to the main hall for vespers. The other monks tried to bolt themselves in for safety, but Becket said to them, "It is not right to make a fortress out of the house of prayer!," ordering them to reopen the doors.

The four knights, wielding drawn swords, ran into the room saying "Where is Thomas Becket, traitor to the King and country?!". The knights found Becket in a spot near a door to the monastic cloister, the stairs into the crypt, and the stairs leading up into the quire of the cathedral, where the monks were chanting vespers. Upon seeing them, Becket said, "I am no traitor and I am ready to die." One knight grabbed him and tried to pull him outside, but Becket grabbed onto a pillar and bowed his head to make peace with God.

Several contemporary accounts of what happened next exist; of particular note is that of Grim, who was wounded in the attack. This is part of his account:

...the impious knight... suddenly set upon him and [shaved] off the summit of his crown which the sacred chrism consecrated to God... Then, with another blow received on the head, he remained firm. But with the third the stricken martyr bent his knees and elbows, offering himself as a living sacrifice, saying in a low voice, "For the name of Jesus and the protection of the church I am ready to embrace death." But the third knight inflicted a grave wound on the fallen one; with this blow... his crown, which was large, separated from his head so that the blood turned white from the brain yet no less did the brain turn red from the blood; it purpled the appearance of the church... The fifth – not a knight but a cleric who had entered with the knights... placed his foot on the neck of the holy priest and precious martyr and (it is horrible to say) scattered the brains with the blood across the floor, exclaiming to the rest, "We can leave this place, knights, he will not get up again."

Another account can be found in Expugnatio Hibernica ("Conquest of Ireland", 1189) written by Gerald of Wales.

After Becket's death

Following Becket's death, the monks prepared his body for burial. According to some accounts, it was discovered that Becket had worn a hairshirt under his archbishop's garments—a sign of penance. Soon after, the faithful throughout Europe began venerating Becket as a martyr, and on 21 February 1173—little more than two years after his death—he was canonised by Pope Alexander III in St Peter's Church in Segni. In 1173, Becket's sister Mary was appointed Abbess of Barking as reparation for the murder of her brother. On 12 July 1174, in the midst of the Revolt of 1173–74, Henry humbled himself with public penance at Becket's tomb as well as at the church of St. Dunstan's, which became one of the most popular pilgrimage sites in England.

Becket's assassins fled north to de Morville's Knaresborough Castle, where they remained for about a year. De Morville also held property in Cumbria and this may also have provided a convenient bolt-hole, as the men prepared for a longer stay in the separate kingdom of Scotland. They were not arrested and neither did Henry confiscate their lands, but he did not help them when they sought his advice in August 1171. Pope Alexander excommunicated all four. Seeking forgiveness, the assassins travelled to Rome and were ordered by the Pope to serve as knights in the Holy Lands for a period of fourteen years.

This sentence also inspired the Knights of Saint Thomas, incorporated in 1191 at Acre, and which was to be modelled on the Teutonic Knights. This was the only military order native to England (with chapters in not only Acre, but London, Kilkenny, and Nicosia), just as the Gilbertine Order was the only monastic order native to England. Nevertheless, Henry VIII dissolved both of these English institutions at the time of the Reformation, rather than merging them with foreign orders or nationalising them as elements of the Protestant Church of England.

The monks were afraid that Becket's body might be stolen. To prevent this, Becket's remains were placed beneath the floor of the eastern crypt of the cathedral. A stone cover was placed over the burial place with two holes where pilgrims could insert their heads and kiss the tomb; this arrangement is illustrated in the "Miracle Windows" of the Trinity Chapel. A guard chamber (now called the Wax Chamber) had a clear view of the grave. In 1220, Becket's bones were moved to a new gold-plated and bejewelled shrine behind the high altar in the Trinity Chapel. The shrine was supported by three pairs of pillars, placed on a raised platform with three steps. This is also illustrated in one of the miracle windows. Canterbury, because of its religious history, had always seen many pilgrims, and after the death of Thomas Becket their numbers rose rapidly.

Cult in the Middle Ages

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

St Thomas Becket's consecration, death and burial, at wall paintings in Santa Maria de Terrassa (Terrassa, Catalonia, Spain), romanesque frescoes, c. 1200

St Thomas Becket's consecration, death and burial, at wall paintings in Santa Maria de Terrassa (Terrassa, Catalonia, Spain), romanesque frescoes, c. 1200

Candle marking the former spot of the shrine of Thomas Becket, at Canterbury Cathedral

Candle marking the former spot of the shrine of Thomas Becket, at Canterbury Cathedral

In Scotland, King William the Lion ordered the building of Arbroath Abbey in 1178. On completion in 1197 the new foundation was dedicated to Becket, whom the king had known personally while at the English court as a young man.

On 7 July 1220, in the 50th jubilee year of his death, Becket's remains were moved from this first tomb to a shrine in the recently completed Trinity Chapel. This act of translation was "one of the great symbolic events in the life of the medieval English Church" and was attended by King Henry III, the papal legate, the Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton and large numbers of dignitaries and magnates secular and ecclesiastical. Thus a "major new feast day was instituted, commemorating the translation, that was celebrated each July almost everywhere in England and also in many French churches". This feast was suppressed in 1536 at the Reformation.

The shrine stood until it was destroyed in 1538, during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, on orders from King Henry VIII. The king also destroyed Becket's bones and ordered that all mention of his name be obliterated.

As the scion of the leading mercantile dynasty of later centuries, Mercers, Becket was very much regarded as a Londoner by the citizens and was adopted as London's co-patron saint with St Paul: both their images appeared on the seals of the city and of the Lord Mayor. The Bridge House Estates seal used only the image of Becket, while the reverse featured a depiction of his martyrdom.

Local legends regarding Becket arose after his canonisation. Though they tend toward typical hagiographical stories, they also display Becket's well-known gruffness. "Becket's Well", in Otford, Kent, is said to have been created after Becket had become displeased with the taste of the local water. Two springs of clear water are said to have bubbled up after he struck the ground with his crozier. The absence of nightingales in Otford is also ascribed to Becket, who is said to have been so disturbed in his devotions by the song of a nightingale that he commanded that none should sing in the town ever again. In the town of Strood, also in Kent, Becket is said to have caused the inhabitants of the town and their descendants to be born with tails. The men of Strood had sided with the king in his struggles against the archbishop, and to demonstrate their support, had cut off the tail of Becket's horse as he passed through the town.

The saint's fame quickly spread throughout the Norman world. The first holy image of Becket is thought to be a mosaic icon still visible in Monreale Cathedral, in Sicily, created shortly after his death. Becket's cousins obtained refuge at the Sicilian court during his exile, and King William II of Sicily wed a daughter of Henry II. Marsala Cathedral in western Sicily is dedicated to St Thomas Becket. Over forty-five medieval chasse reliquaries decorated in champlevé enamel showing similar scenes from Becket's life survive, including the Becket Casket, originally constructed to hold relics of the saint at Peterborough Abbey, and now housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Legacy

- In 1170 the king of Castille Alfonso VIII married Eleanor Plantagenet, the second daughter of Henry II. She honoured Becket with a wall painting of his martyrdom that is preserved in the church of San Nicolás de Soria in Spain. The assassination of Becket made an impact in Spain; within five years after his death there was a church in Salamanca named after him, Iglesia de Santo Tomás Cantuariense.

- Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales is set in a company of pilgrims on their way from Southwark to the shrine of St Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral.

- The story of Becket's life became a popular theme for the medieval Nottingham Alabaster carvers. One set of Becket panels is displayed in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

- The coat of arms of the City of Canterbury, officially registered in 1619, but dating back to at least 1380, is based on the attributed arms of Thomas Becket, Argent, three Cornish choughs proper, with the addition of a chief gules charged with a lion passant guardant or from the Royal Arms of England.

- In 1884, England's poet laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote Becket, a play about Thomas Becket and Henry II. Henry Irving produced the play after Tennyson's death, and was celebrated in the title role.

- Modern works based on the story of Thomas Becket include T. S. Eliot's play Murder in the Cathedral (subsequently adapted as the opera Assassinio nella cattedrale by Ildebrando Pizzetti), Jean Anouilh's play Becket (where Becket is no longer a Norman but a Saxon), which was made into a movie with the same title, and Paul Webb's play Four Nights in Knaresborough. Webb has adapted his play for the screen and sold the rights to Harvey and Bob Weinstein. The struggle between Church's and King's power is a theme of Ken Follett's novel The Pillars of the Earth, of which one of the last scenes features the murder of Thomas Becket. Medieval mystery author Jeri Westerson recreated Chaucer's pilgrims and their time in Canterbury, along with murder and the theft of Becket's bones in her fourth novel in the Crispin Guest series Troubled Bones. An oratorio by David Reeves entitled Becket (The Kiss of Peace) premiered in 2000 at the Canterbury Cathedral, where the actual event took place, as a part of the Canterbury Festival and was used as a fundraiser for the Prince's Trust.

- The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a nonprofit, nonpartisan, interfaith, legal and educational institute dedicated to protecting the free expression of all religious traditions, took its inspiration and namesake from Thomas Becket.

- In a 2006 poll by BBC History magazine for "worst Briton" of the previous millennium, Becket came second behind Jack the Ripper. The poll was dismissed as "daft" in The Guardian, and the result disputed by Anglicans and Catholics. Historians had nominated one person per century, and for the 12th century John Hudson chose Becket for being "greedy", "hypocritical", "founder of gesture politics" and "master of the soundbite". The magazine editor suggested most other nominees were too obscure for voters, as well as saying, "In an era when thumbscrews, racks and burning alive could be passed off as robust law and order—being guilty of 'gesture politics' might seem something of a minor charge."

- There are many churches named after Thomas Becket in the UK, including Cathedral Church of St Thomas of Canterbury, Portsmouth, St Thomas of Canterbury Church, Canterbury, Church of St Thomas the Martyr, Monmouth, St Thomas à Becket Church, Pensford, St Thomas à Becket Church, Widcombe, Church of St Thomas à Becket, Capel, St Thomas the Martyr, Bristol and St Thomas the Martyr's Church, Oxford, and in France, including Église Saint-Thomas de Cantorbéry at Mont-Saint-Aignan (Upper-Normandy), Église Saint-Thomas-Becket at Gravelines (Nord-Pas-de-Calais), Église Saint-Thomas Becket at Avrieux (Rhône-Alpes), Église saint-Thomas Becket at Bénodet (Brittany), etc.

- As part of his obligations in contrition to Henry, William de Tracy significantly enlarged and re-dedicated the parish church in Lapford, Devon to St Thomas of Canterbury as it lay within his manor of Bradninch. The martyrdom is commemorated by the Lapford Revel to this day.

- There are many schools named after Thomas Becket in Great Britain, including Becket Keys Church of England School and St Thomas of Canterbury Church of England Aided Junior School.

- There is a section of the city of Esztergom, Hungary named Szenttamás ("Saint Thomas"), on a hill called "Szent Tamás", both named after Thomas Becket, who was a classmate and friend of Lucas, Archbishop of Esztergom in Paris.

- Among the possessions of the treasury of the Fermo Cathedral is the Fermo chasuble of St. Thomas Becket, on display at Museo Diocesano.

- Thomas Becket is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 29 December.

-

Wall painting of Thomas Becket's martyrdom painted in the 1330s in the parish church of St Peter ad Vincula, South Newington, Oxfordshire

-

The coat of arms of the City of Canterbury combines the attributed arms of Thomas Becket (three Cornish choughs) with a lion from the royal arms of England