Feastday: June 1

Birth: 100

Death: 165

Christian apologist, born at Flavia Neapolis, about A.D. 100, converted to Christianity about A.D. 130, taught and defended the Christian religion in Asia Minor and at Rome, where he suffered martyrdom about the year 165. Two "Apologies" bearing his name and his "Dialogue with the Jew Tryphon" have come down to us. Leo XIII had a Mass and an Office composed in his honour and set his feast for 14 April.

Life

Among the Fathers of the second century his life is the best known, and from the most authentic documents. In both "Apologies" and in his "Dialogue" he gives many personal details, e.g. about his studies in philosophy and his conversion; they are not, however, an autobiography, but are partly idealized, and it is necessary to distinguish in them between poetry and truth; they furnish us however with several precious and reliable clues. For his martyrdom we have documents of undisputed authority. In the first line of his "Apology" he calls himself "Justin, the son of Priscos, son of Baccheios, of Flavia Neapolis, in Palestinian Syria". Flavia Neapolis, his native town, founded by Vespasian (A.D. 72), was built on the site of a place called Mabortha, or Mamortha, quite near Sichem (Guérin, "Samarie", I, Paris, 1874, 390-423; Schürer, "History of the Jewish People", tr., I, Edinburgh, 1885). Its inhabitants were all, or for the most part, pagans. The names of the father and grandfather of Justin suggest a pagan origin, and he speaks of himself as uncircumcised (Dialogue, xxviii). The date of his birth is uncertain, but would seem to fall in the first years of the second century. He received a good education in philosophy, an account of which he gives us at the beginning of his "Dialogue with the Jew Tryphon"; he placed himself first under a Stoic, but after some time found that he had learned nothing about God and that in fact his master had nothing to teach him on the subject. A Peripatetic whom he then found welcomed him at first but afterwards demanded a fee from him; this proved that he was not a philosopher. A Pythagorean refused to teach him anything until he should have learned music, astronomy, and geometry. Finally a Platonist arrived on the scene and for some time delighted Justin. This account cannot be taken too literally; the facts seem to be arranged with a view to showing the weakness of the pagan philosophies and of contrasting them with the teachings of the Prophets and of Christ. The main facts, however, may be accepted; the works of Justin seem to show just such a philosophic development as is here described, Eclectic, but owing much to Stoicism and more to Platonism. He was still under the charm of the Platonistic philosophy when, as he walked one day along the seashore, he met a mysterious old man; the conclusion of their long discussion was that he soul could not arrive through human knowledge at the idea of God, but that it needed to be instructed by the Prophets who, inspired by the Holy Ghost, had known God and could make Him known ("Dialogue", iii, vii; cf. Zahm, "Dichtung and Wahrheit in Justins Dialog mit dem Jeden Trypho" in "Zeitschr. für Kirchengesch.", VIII, 1885-1886, 37-66).

The "Apologies" throw light on another phase of the conversion of Justin: "When I was a disciple of Plato", he writes, "hearing the accusations made against the Christians and seeing them intrepid in the face of death and of all that men fear, I said to myself that it was impossible that they should be living in evil and in the love of pleasure" (II Apol., xviii, 1). Both accounts exhibit the two aspects of Christianity that most strongly influenced St. Justin; in the "Apologies" he is moved by its moral beauty (I Apol., xiv), in the "Dialogue" by its truth. His conversion must have taken place at the latest towards A.D. 130, since St. Justin places during the war of Bar-Cocheba (132-135) the interview with the Jew Tryphon, related in his "Dialogue". This interview is evidently not described exactly as it took place, and yet the account cannot be wholly fictitious. Tryphon, according to Eusebius (Hist. eccl., IV, xviii, 6), was "the best known Jew of that time", which description the historian may have borrowed from the introduction to the "Dialogue", now lost. It is possible to identify in a general way this Tryphon with the Rabbi Tarphon often mentioned in the Talmud (Schürer, "Gesch. d. Jud. Volkes", 3rd ed., II, 377 seq., 555 seq., cf., however, Herford, "Christianity in Talmud and Midrash", London, 1903, 156). The place of the interview is not definitely told, but Ephesus is clearly enough indicated; the literary setting lacks neither probability nor life, the chance meetings under the porticoes, the groups of curious onlookers who stop a while and then disperse during the inteviews, offer a vivid picture of such extemporary conferences. St. Justin lived certainly some time at Ephesus; the Acts of his martyrdom tell us that he went to Rome twice and lived "near the baths of Timothy with a man named Martin". He taught school there, and in the aforesaid Acts of his martyrdom we read of several of his disciples who were condemned with him.

In his second "Apology" (iii) Justin says: "I, too, expect to be persecuted and to be crucified by some of those whom I have named, or by Crescens, that friend of noise and of ostentation." Indeed Tatian relates (Discourse, xix) that the Cynic philosopher Crescens did pursue him and Justin; he does not tell us the result and, moreover, it is not certain that the "Discourse" of Tatian was written after the death of Justin. Eusebius (Hist. eccl., IV, xvi, 7, 8) says that it was the intrigues of Crescens which brought about the death of Justin; this is credible, but not certain; Eusebius has apparently no other reason for affirming it than the two passages cited above from Justin and Tatian. St. Justin was condemned to death by the prefect, Rusticus, towards A.D. 165, with six companions, Chariton, Charito, Evelpostos, Pćon, Hierax, and Liberianos. We still have the authentic account of their martyrdom ("Acta SS.", April, II, 104-19; Otto, "Corpus Apologetarum", III, Jena, 1879, 266-78; P. G., VI, 1565-72). The examination ends as follows:

"The Prefect Rusticus says: Approach and sacrifice, all of you, to the gods. Justin says: No one in his right mind gives up piety for impiety. The Prefect Rusticus says: If you do not obey, you will be tortured without mercy. Justin replies: That is our desire, to be tortured for Our Lord, Jesus Christ, and so to be saved, for that will give us salvation and firm confidence at the more terrible universal tribunal of Our Lord and Saviour. And all the martyrs said: Do as you wish; for we are Christians, and we do not sacrifice to idols. The Prefect Rusticus read the sentence: Those who do not wish to sacrifice to the gods and to obey the emperor will be scourged and beheaded according to the laws. The holy martyrs glorifying God betook themselves to the customary place, where they were beheaded and consummated their martyrdom confessing their Saviour."

Works

Justin was a voluminous and important writer. He himself mentions a "Treatise against Heresy" (I Apology, xxvi, 8); St. Irenćus (Adv. Hćr., IV, vi, 2) quotes a "Treatise against Marcion" which may have been only a part of the preceding work. Eusebius mentions both (Hist. eccl., IV, xi, 8-10), but does not seem to have read them himself; a little further on (IV, xviii) he gives the following list of Justin's works: "Discourse in favour of our Faith to Antoninus Pius, to his sons, and to the Roman Senate"; an "Apology" addressed to Marcus Aurelius; "Discourse to the Greeks"; another discourse called "A Refutation"; "Treatise on the Divine Monarchy"; a book called "The Psalmist"; "Treatise on the soul"; "Dialogue against the Jews", which he had in the city of Ephesus with Tryphon, the most celebrated Israelite of that time. Eusebius adds that many more of his books are to be found in the hands of the brethren. Later writers add nothing certain to this list, itself possibly not altogether reliable. There are extant but three works of Justin, of which the authenticity is assured: the two "Apologies" and the "Dialogue". They are to be found in two manuscripts: Paris gr. 450, finished on 11 September, 1364; and Claromont. 82, written in 1571, actually at Cheltenham, in the possession of M.T.F. Fenwick. The second is only a copy of the first, which is therefore our sole authority; unfortunately this manuscript is very imperfect (Harnack, "Die Ueberlieferung der griech. Apologeten" in "Texte and Untersuchungen", I, Leipzig, 1883, i, 73-89; Archambault, "Justin, Dialogue a vec Tryphon", Paris, 1909, p. xii-xxxviii). There are many large gaps in this manuscript, thus II Apol., ii, is almost entirely wanting, but it has been found possible to restore the manuscript text from a quotation of Eusebius (Hist. eccl., IV, xvii). The "Dialogue" was dedicated to a certain Marcus Pompeius (exli, viii); it must therefore have been preceded by a dedicatory epistle and probably by an introduction or preface; both are lacking. In the seventy-fourth chapter a large part must also be missing, comprising the end of the first book and the beginning of the second (Zahn, "Zeitschr. f. Kirchengesch.", VIII, 1885, 37 sq., Bardenhewer, "Gesch. der altkirchl. Litter.", I, Freiburg im Br., 1902, 210). There are other less important gaps and many faulty transcriptions. There being no other manuscript, the correction of this one is very difficult; conjectures have been often quite unhappy, and Krüger, the latest editor of the "Apology", has scarsely done more than return to the text of the manuscript.

In the manuscript the three works are found in the following order: second "Apology", first "Apology", the "Dialogue". Dom Maran (Paris, 1742) re-established the original order, and all other editors have followed him. There could not be as a matter of fact any doubt as to the proper order of the "Apologies", the first is quoted in the second (iv, 2; vi, 5; viii, 1). The form of these references shows that Justin is referring, not to a different work, but to that which he was then writing (II Apol., ix, 1, cf. vii, 7; I Apol., lxiii, 16, cf. xxxii, 14; lxiii, 4, cf. xxi,1;lxi, 6, cf. lxiv, 2). Moreover, the second "Apology" is evidently not a complete work independent of the first, but rather an appendix, owing to a new fact that came to the writer's knowledge, and which he wished to utilize without recasting both works. It has been remarked that Eusebius often alludes to the second "Apology" as the first (Hist. eccl., IV, viii, 5; IV, xvii, 1), but the quotations from Justin by Eusebius are too inexact for us to attach much value to this fact (cf. Hist. eccl., IV, xi, 8; Bardenhewer, op. cit., 201). Probably Eusebius also erred in making Justin write one apology under Antoninus (161) and another under Marcus Aurelius. The second "Apology", known to no other author, doubtless never existed (Bardenhewer, loc. cit.; Harnack, "Chronologie der christl. Litter.", I, Leipzig, 1897, 275). The date of the "Apology" cannot be determined by its dedication, which is not certain, but can be established with the aid of the following facts: it is 150 years since the birth of Christ (I, xlvi, 1); Marcion has already spread abroad his error (I, xxvi, 5); now, according to Epiphanius (Hćres., xlii, 1), he did not begin to teach until after the death of Hyginus (A.D. 140). The Prefect of Egypt, Felix (I, xxix, 2), occupied this charge in September, 151, probably from 150 to about 154 (Grenfell-Hunt, "Oxyrhinchus Papyri", II, London, 1899, 163, 175; cf. Harnack, "Theol. Literaturzeitung", XXII, 1897, 77). From all of this we may conclude that the "Apology" was written somewhere between 153 and 155. The second "Apology", as already said, is an appendix to the first and must have been written shortly afterwards. The Prefect Urbinus mentioned in it was in charge from 144 to 160. The "Dialogue" is certainly later than the "Apology" to which it refers ("Dial.", cxx, cf. "I Apol.", xxvi); it seems, moreover, from this same reference that the emperors to whom the "Apology" was addressed were still living when the "Dialogue" was written. This places it somewhere before A.D. 161, the date of the death of Antoninus.

The "Apology" and the "Dialogue" are difficult to analyse, for Justin's method of composition is free and capricious, and defies our habitual rules of logic. The content of the first "Apology" (Viel, "Justinus des Phil. Rechtfertigung", Strasburg, 1894, 58 seq.) is somewhat as follows:

- i-iii: exordium to the emperors: Justin is about to enlighten them and free himself of responsibility, which will now be wholly theirs.

- iv-xii: first part or introduction:

- the anti-Christian procedure is iniquitous: they persecute in the Christians a name only (iv, v);

- Christians are neither Atheists nor criminals (vi, vii);

- they allow themselves to be killed rather than deny their God (viii);

- they refuse to adore idols (ix, xii);

- conclusion (xii).

- xiii-lxvii: Second part (exposition and demonstration of Christianity):

- Christians adore the crucified Christ, as well as God (xiii);

- Christ is their Master; moral precepts (xiv-xvii);

- the future life, judgement, etc. (xviii-xx).

- Christ is the Incarnate Word (xxi-lx);

- comparison with pagan heroes, Hermes, Ćsculapius, etc. (xxi-xxii);

- superiority of Christ and of Christianity before Christ (xlvi).

- The similarities that we find in the pagan worship and philosophy come from the devils (liv-lx).

- Description of Christian worship: baptism (lxi);

- the Eucharist (lxv-lxvi);

- Sunday-observance (lxvii).

Second "Apology":

- Recent injustice of the Prefect Urbinus towards the Christians (i-iii).

- Why it is that God permits these evils: Providence, human liberty, last judgement (iv-xii).

The "Dialogue" is much longer than the two apologies taken together ("Apol." I and II in P.G., VI, 328-469; "Dial.", ibid., 472-800), the abundance of exegetical discussions makes any analysis particularly difficult. The following points are noteworthy:

- i-ix. Introduction: Justin gives the story of his philosophic education and of this conversion. One may know God only through the Holy Ghost; the soul is not immortal by its nature; to know truth it is necessary to study the Prophets.

- x-xxx: On the law. Tryphon reproaches the Christians for not observing the law. Justin replies that according to the Prophets themselves the law should be abrogated, it had only been given to the Jews on account of their hardness. Superiority of the Christian circumcision, necessary even for the Jews. The eternal law laid down by Christ.

- xxxi-cviii: On Christ: His two comings (xxxi sqq.); the law a figure of Christ (xl-xlv); the Divinity and the pre-existence of Christ proved above all by the Old Testament apparitions (theophanies) (lvi-lxii); incarnation and virginal conception (lxv sqq.); the death of Christ foretold (lxxxvi sqq.); His resurrection (cvi sqq.).

- viii to the end: On the Christians. The conversion of the nations foretold by the Prophets (cix sqq.); Christians are a holier people than the Jews (cxix sqq.); the promises were made to them (cxxi); they were prefigured in the Old Testament (cxxxiv sqq.). The "Dialogue" concludes with wishes for the conversion of the Jews.

Besides these authentic works we possess others under Justin's name that are doubtful or apocryphal.

The "Answers to the Orthodox" was re-edited in a different and more primitive form by Papadopoulos-Kerameus (St. Petersburg, 1895), from a Constantinople manuscript which ascribed the work to Theodoret. Though this ascription was adopted by the editor, it has not been generally accepted. Harnack has studied profoundly these four books and maintains, not without probability, that they are the work of Diodorus of Tarsus (Harnack, "Diodor von Tarsus., vier pseudojustinische Schriften als Eigentum Diodors nachgewiesen" in "Texte und Untersuch.", XII, 4, Leipzig, 1901).

The only pagan quotations to be found in Justin's works are from Homer, Euripides, Xenophon, Menander, and especially Plato (Otto, II, 593 sq.). His philosophic development has been well estimated by Purves ("The Testimony of Justin Martyr to early Christianity", London, 1882, 132): "He appears to have been a man of moderate culture. He was certainly not a genius nor an original thinker." A true eclectic, he draws inspiration from different systems, especially from Stoicism and Platonism. Weizsäcker (Jahrbücher f. Protest. Theol., XII, 1867, 75) thought he recognized a Peripatetic idea, or inspiration, in his conception of God as immovable above the heavens (Dial., cxxvii); it is much more likely an idea borrowed from Alexandrian Judaism, and one which furnished a very efficacious argument to Justin in his anti-Jewish polemic. In the Stoics Justin admires especially their ethics (II Apol., viii, 1); he willingly adopts their theory of a universal conflagration (ekpyrosis). In I Apol., xx, lx; II, vii, he adopts, but at the same time transforms, their concept of the seminal Word (logos spermatikos). However, he condemns their Fatalism (II Apol., vii) and their Atheism (Dial., ii). His sympathies are above all with Platonism. He likes to compare it with Christanity; apropos of the last judgment, he remarks, however (I Apol., viii, 4), that according to Plato the punishment will last a thousand years, whereas according to the Christians it will be eternal; speaking of creation (I Apol., xx, 4; lix), he says that Plato borrowed from Moses his theory of formless matter; similarly he compares Plato and Christianity apropos of human responsibility (I Apol., xliv, 8) and the Word and the Spirit (I Apol., lx). However, his acquaintance with Plato was superficial; like his contemporaries (Philo, Plutarch, St. Hippolytus), he found his chief inspiration in the Timćus. Some historians have pretended that pagan philosophy entirely dominated Justin's Christianity (Aubé, "S. Justin", Paris, 1861), or at least weakened it (Engelhardt, "Das Christentum Justins des Märtyrers", Erlangen, 1878). To appreciate fairly this influence it is necessary to remember that in his "Apology" Justin is seeking above all the points of contact between Hellenism and Christianity. It would certainly be wrong to conclude from the first "Apology" (xxii) that Justin actually likens Christ to the pagan heroes of semi-heroes, Hermes, Perseus, or Ćsculapius; neither can we conclude from his first "Apology" (iv, 8 or vii, 3, 4) that philosophy played among the Greeks the same role that Christianity did among the barbarians, but only that their position and their reputation were analogous.

In many passages, however, Justin tries to trace a real bond between philosophy and Christianity: according to him both the one and the other have a part in the Logos, partially disseminated among men and wholly manifest in Jesus Christ (I, v, 4; I, xlvi; II, viii; II, xiii, 5, 6). The idea developed in all these passages is given in the Stoic form, but this gives to its expression a greater worth. For the Stoics the seminal Word (logos spermatikos) is the form of every being; here it is the reason inasmuch as it partakes of God. This theory of the full participation in the Divine Word (Logos) by the sage has its full value only in Stoicism (see LOGOS). In Justin thought and expression are antithetic, and this lends a certain incoherence to the theory; the relation established between the integral Word, i.e. Jesus Christ, and the partial Word disseminated in the world, is more specious than profound. Side by side with this theory, and quite different in its origin and scope, we find in Justin, as in most of his contemporaries, the conviction that Greek philosophy borrowed from the Bible: it was by stealing from Moses and the Prophets that Plato and the other philosophers developed their doctrines (I, xliv, lix, ls). Despite the obscurities and incoherences of this thought, he affirms clearly and positively the transcendent character of Christianity: "Our doctrine surpasses all human doctrine because the real Word became Christ who manifested himself for us, body, word and soul." (II, Apol., x, 1.) This Divine origin assures Christianity an absolute truth (II, xiii, 2) and gives to the Christians complete confidence; they die for Christ's doctrine; no one died for that of Socrates (II, x, 8). The first chapters of the "Dialogue" complete and correct these ideas. In them the rather complaisant syncretism of the "Apology" disappears, and the Christian thought is stronger.

Justin's chief reproach to the philosophers is their mutual divisions; he attributes this to the pride of the heads of sects and the servile acquiesence of their adherents; he also says a little later on (vi): "I care neither for Plato nor for Pythagoras." From it all he concludes that for the pagans philosophy is not a serious or profound thing; life does not depend on it, nor action: "Thou art a friend of discourse", says the old man to him before his conversion, "but not of action nor of truth" (iv). For Platonism he retained a kindly feeling as for a study dear in childhood or in youth. Yet he attacks it on two essential points: the relation between God and man, and the nature of the soul (Dial., iii, vi). Nevertheless he still seems influenced by it in his conception of the Divine transcendency and the interpretation that he gives to the aforesaid theophanies.

That which Justin despairs of attaining through philosophy he is now sure of possessing through Jewish and Christian revelation. He admits that the soul can naturally comprehend that God is, just as it understands that virtue is beautiful (Dial., iv) but he denies that the soul without the assistance of the Holy Ghost can see God or contemplate Him directly through ecstasy, as the Platonic philosophers contended. And yet this knowledge of God is necessary for us: "We cannot know God as we know music, arithmetic or astronomy" (iii); it is necessary for us to know God not with an abstract knowledge but as we know any person with whom we have relations. Thr problem which it seems impossible to solve is settled by revelation; God has spoken directly to the Prophets, who in their turn have made Him known to us (viii). It is the first time in Christian theology that we find so concise an explanation of the difference which separates Christian revelation from human speculation. It does away with the confusion that might arise from the theory, taken from the "Apology", of the partial Logos and the Logos absolute or entire.

A. The Old Testament

For Philo the Bible is bery particularly the Pentateuch (Ryle, "Philo and Holy Scripture", XVII, London, 1895, 1-282). In keeping with the difference of his purpose, Justin has other preferences. He quotes the Pentateuch often and liberally, especially Genesis, Exodus, and Deuteronomy; but he quotes still more frequently and at greater length the Psalms and the Books of Prophecy -- above all, Isaias. The Books of Wisdom are seldom quoted, the historical books still less. The books that we never find in his works are Judges, Esdras (except one passage which is attributed to him by mistake-Dial., lxxii), Tobias, Judith, Ester, Canticles, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Abdias, Nahum, Habacuc, Sophonias, Aggeus. It has been noticed, too (St. John Thackeray in "Journ. of Theol. Study", IV, 1903, 265, n.3), that he never cites the last chapters of Jeremias (apropos of the first "Apology", xlvii, Otto is wrong in his reference to Jer., 1, 3). Of these omissions the most noteworthy is that of Wisdom, precisely on account of the similarity of ideas. It is to be noted, moreover, that this book, surely used in the New Testament, cited by St. Clement of Rome (xxvii, 5) and later by St. Irenćus (Eusebius, Hist. eccl., V, xxvi), is never met with in the works of the apologists (the reference of Otto to Tatian, vii, is inexact). On the other hand one finds in Justin some apocryphal texts: pseudo-Esdras (Dial., lxxii), pseudo-Jeremias (ibid.), Ps. xevi (xcv), 10 (Dial., lxxii; I Apol., xli); sometimes also errors in ascribing quotations: Zacharias for Malachias (Dial., xlix), Osee for Zacharias for Malachias (Dial., xiv). For the Biblical text of Justin, see Swete, "Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek", Cambridge, 1902, 417-24.

B. The New Testament

The testimony of Justin is here of still greater importance, especially for the Gospels, and has been more often discussed. The historical side of the question is given by W. Bousset, "Die Evangeliencitaten Justins" (Göttingen, 1891), 1-12, and since then, by Baldus, "Das Verhältniss Justins der Märt. zu unseren synopt. Evangelien" (Münster, 1895); Lippelt, "Quć fuerint Justini mart. apomnemoneumata quaque ratione cum forma Evangeliorum syro-latina cohćserint" (Halle, 1901). The books quoted by Justin are called by him "Memoirs of the Apostles". This term, otherwise very rare, appears in Justin quite probably as an analogy with the "Memorabilia" of Xenophon (quoted in "II Apol.", xi, 3) and from a desire to accommodate his language to the habits of mind of his readers. At any rate it seems that henceforth the word "gospels" was in current usage; it is in Justin that we find it for the first time used in the plural, "the Apostles in their memoirs that are called gospels" (I Apol., lxvi, 3). These memoirs have authority, not only because they relate the words of Our Lord (as Bossuet contends, op. cit., 16 seq.), but because, even in their narrative parts, they are considered as Scripture (Dial., xlix, citing Matt., xvii, 13). This opinion of Justin is upheld, moreover, by the Church who, in her public service reads the memoirs of the Apostles as well as the writings of the prophets (I Apol., lxvii, 3). These memoirs were composed by the Apostles and by those who followed them (Dial., ciii); he refers in all probability to the four Evangelists, i.e. to two Apostles and two disciples of Christ (Stanton, "New Testament Canon" in Hastings, "Dictionary of the Bible", III, 535). The authors, however, are not named: once (Dial., ciii) he mentions the "memoirs of Peter", but the text is very obscure and uncertain (Bousset, op. cit., 18).

All facts of the life of Christ that Justin takes from these memoirs are found indeed in our Gospels (Baldus, op. cit., 13 sqq.); he adds to them a few other and less important facts (I Apol., xxxii; xxxv; Dial., xxxv, xlvii, li, lxxviii), but he does not assert that he found them in the memoirs. It is quite probable that Justin used a concordance, or harmony, in which were united the three synoptic Gospels (Lippelt, op. cit., 14, 94) and it seems that the text of this concordance resembled in more than one point the so-called Western text of the Gospels (cf. ibid., 97). Justin's dependence on St. John is indisputably established by the facts which he takes from Him (I Apol., lxi, 4, 5; Dial., lxix, lxxxviii), still more by the very striking similarity in vocabulary and doctrine. It is certain, however, that Justin does not use the fourth Gospel as abundantly as he does the others (Purves, op. cit., 233); this may be owing to the aforesaid concordance, or harmony, of the synoptic Gospels. He seems to use the apocryphal Gospel of Peter (I Apol., xxxv, 6; cf. Dial., ciii; Revue Biblique, III, 1894, 531 sqq.; Harnack, "Bruchstücke des Evang. des Petrus", Leipzig, 1893, 37). His dependence on the Protevangelium of James (Dial., lxxviii) doubtful.

Apologetical method

Justin's attitude towards philosophy, described above, reveals at once the tendency of his polemics; he never exibits the indignation of a Tatian or even of a Tertullian. To the hideous calumnies spread abroad against the Christians he sometimes answers, as do the other apologists, by taking the offensive and attacking pagan morality (I Apol., xxvii; II, xii, 4, 5), but he dislikes to insist on these calumnies: the interlocutor in the "Dialogue" (ix) he is careful to ignore those who would trouble him with their loud laughter. He has not the eloquence of Tertullian, and can obtain a hearing only in a small circle of men capable of understanding reason and of being moved by an idea. His chief argument, and one calculated to convert this hearers as it had converted him (II Apol., xii), is the great new fact of Christian morality. He speaks of men and women who have no fear of death (I Apol., ii, xi, xlv; II, ii; Dial., xxx), who prefer truth to life (I Apol., ii; II, iv) and are yet ready to await the time allotted by God (II, iv1); he makes known their devotion to their children (I, xxvii), their charity even towards their enemies, and their desire to save them (I Apol., lvii; Dial., cxxxiii), their patience and their prayers in persecution (Dial., xviii), their love of mankind (Dial., xciii, cx). When he contrasts the life that they led in paganism with their Christian life (I Apol., xiv), he expresses the same feeling of deliverance and exaltation as did St. Paul (I Cor., vi, II). He is careful, moreover, to emphasize, especially from the Sermon on the Mount, the moral teaching of Christ so as to show in it the real source of these new virtues (I Apol., xv-xviii). Throughout his exposé of the new religion it is Christian chastity and the courage of the martyrs that he most insists upon.

The rational evidences of Christianity Justin finds especially in the prophecies; he gives to this argument more than a third of his "Apology" (xxx-liii) and almost the entire "Dialogue". When he is disputing with the pagans he is satisfied with drawing attention to the fact that the books of the Prophets were long anterior to Christ, guaranteed as to their authenticity by the Jews themselves, and says that they contain prophecies concerning the life of Christ and the spread of the Church that can only be explained by a Divine revelation (I Apol., xxxi). In the "Dialogue", arguing with Jews, he can assume this revelation which they also recognize, and he can invoke the Scriptures as sacred oracles. These evidences of the prophecies are for him absolutely certain. "Listen to the texts which I am about to cite; it is not necessary for me to comment upon them, but only for you to hear them" (Dial., liii; cf. I Apol., xxx, liii). Nevertheless he recognizes that Christ alone could have given the explanation of them (I Apol., xxxii; Dial., lxxvi; cv); to understand them the men and women of his time must have the interior dispositions that make the true Christian (Dial., cxii), i.e., Divine grace is necessary (Dial., vii, lviii, xcii, cxix). He also appeals to miracles (Dial., vii; xxxv; lxix; cf. II Apol., vi), but with less insistence than to the prophecies.

THEOLOGY

God. Justin's teaching concerning God has been very diversely interpreted, some seeing in it nothing but a philosophic speculation (Engelhardt, 127 sq., 237 sqq.), others a truly Christian faith (Flemming, "Zur Beurteilung des Christentums Justins des Märtyrers", Leipzig, 1893, 70 sqq.; Stählin, "Justin der Märtyrer und sein neuester Beurtheiler", 34 sqq., Purves, op. cit., 142 sqq.). In reality it is possible to find in it these two tendencies: on one side the influence of philosophy betrays itself in his concept of the Divine transcendency, thus God is immovable (I Apol., ix; x, 1; lxiii, 1; etc.); He is above the heaven, can neither be seen nor enclosed within space (Dial., lvi, lx, cxxvii); He is called Father, in a philosophic and Platonistic sense, inasmuch as He is the Creator of the world (I Apol., xlv, 1; lxi, 3; lxv, 3; II Apol., vi, 1, etc.). On the other hand we see the God of the Bible in his all-powerful (Dial., lxxxiv; I Apol., xix, 6), and merciful God (Dial., lxxxiv; I Apol., xix, 6), and merciful God (Dial., cviii, lv, etc.); if He ordained the Sabbath it was not that He had need of the homage of the Jews, but that He desired to attach them to Himself (Dial., xxii); through His mercy He preserved among them a seed of salvation (lv); through His Divine Providence He has rendered the nations worthy of their inheritance (cxviiicxxx); He delays the end of the world on account of the Christians (xxxix; I Apol., xxviii, xlv). And the great duty of man is to love Him (Dial., xciii).

2nd century Catholic apologist and martyr For the Latin historian, see Justin (historian).

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

Aquinas, Scotus, and Ockham Aquinas, Scotus, and Ockham |

| Ethics |

|

| Schools |

|

| Philosophers |

Ancient

|

Postclassical

|

Modern

|

Contemporary

|

|

|

|

Justin Martyr (Greek: Ἰουστῖνος ὁ μάρτυς; c. 100 – c. 165) was an early Christian apologist and philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and a dialogue did survive. The First Apology, his most well-known text, passionately defends the morality of the Christian life, and provides various ethical and philosophical arguments to convince the Roman emperor, Antoninus, to abandon the persecution of the Church. Further, he also indicates, as St. Augustine would later, regarding the "true religion" that predated Christianity, that the "seeds of Christianity" (manifestations of the Logos acting in history) actually predated Christ's incarnation. This notion allows him to claim many historical Greek philosophers (including Socrates and Plato), in whose works he was well studied, as unknowing Christians.

Justin was martyred, alongside some of his students, and is venerated as a saint by the Catholic Church, the Anglican Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Oriental Orthodox Churches.

Life

A bearded Justin Martyr presenting an open book to a Roman emperor. Engraving by Jacques Callot.

A bearded Justin Martyr presenting an open book to a Roman emperor. Engraving by Jacques Callot.

Justin Martyr was born around AD 100 at Flavia Neapolis (today Nablus) in Samaria. He was Greek but self-identified as Samaritan. His family may have been pagan, since he was uncircumcised, and defined himself as a Gentile. His grandfather, Bacchius, had a Greek name, while his father, Priscus, bore a Latin name, which has led to speculations that his ancestors may have settled in Neapolis soon after its establishment or that they were descended from a Roman "diplomatic" community that had been sent there.

In the opening of the Dialogue, Justin describes his early education, stating that his initial studies left him unsatisfied due to their failure to provide a belief system that would afford theological and metaphysical inspiration to their young pupil. He says he tried first the school of a Stoic philosopher, who was unable to explain God's being to him. He then attended a Peripatetic philosopher but was put off because the philosopher was too eager for his fee. Then he went to hear a Pythagorean philosopher who demanded that he first learn music, astronomy, and geometry, which he did not wish to do. Subsequently, he adopted Platonism after encountering a Platonist thinker who had recently settled in his city.

And the perception of immaterial things quite overpowered me, and the contemplation of ideas furnished my mind with wings, so that in a little while I supposed that I had become wise; and such was my stupidity, I expected forthwith to look upon God, for this is the end of Plato's philosophy.

Some time afterwards, he chanced upon an old man, possibly a Syrian Christian, in the vicinity of the seashore, who engaged him in a dialogue about God and spoke of the testimony of the prophets as being more reliable than the reasoning of philosophers.

There existed, long before this time, certain men more ancient than all those who are esteemed philosophers, both righteous and beloved by God, who spoke by the Divine Spirit, and foretold events which would take place, and which are now taking place. They are called prophets. These alone both saw and announced the truth to men, neither reverencing nor fearing any man, not influenced by a desire for glory, but speaking those things alone which they saw and which they heard, being filled with the Holy Spirit. Their writings are still extant, and he who has read them is very much helped in his knowledge of the beginning and end of things, and of those matters which the philosopher ought to know, provided he has believed them. For they did not use demonstration in their treatises, seeing that they were witnesses to the truth above all demonstration, and worthy of belief; and those events which have happened, and those which are happening, compel you to assent to the utterances made by them, although, indeed, they were entitled to credit on account of the miracles which they performed, since they both glorified the Creator, the God and Father of all things, and proclaimed His Son, the Christ [sent] by Him: which, indeed, the false prophets, who are filled with the lying unclean spirit, neither have done nor do, but venture to work certain wonderful deeds for the purpose of astonishing men, and glorify the spirits and demons of error. But pray that, above all things, the gates of light may be opened to you; for these things cannot be perceived or understood by all, but only by the man to whom God and His Christ have imparted wisdom.

Moved by the aged man's argument, Justin renounced both his former religious faith and his philosophical background, choosing instead to re-dedicate his life to the service of the Divine. His newfound convictions were only bolstered by the ascetic lives of the early Christians and the heroic example of the martyrs, whose piety convinced him of the moral and spiritual superiority of Christian doctrine. As a result, he thenceforth decided that the only option for him was to travel throughout the land, spreading the knowledge of Christianity as the "true philosophy." His conversion is commonly assumed to have taken place at Ephesus though it may have occurred anywhere on the road from Syria Palestina to Rome.

Mosaic of the beheading of Justin Martyr

Mosaic of the beheading of Justin Martyr

He then adopted the dress of a philosopher himself and traveled about teaching. During the reign of Antoninus Pius (138–161), he arrived in Rome and started his own school. Tatian was one of his pupils. In the reign of Marcus Aurelius, after disputing with the cynic philosopher Crescens, he was denounced by the latter to the authorities, according to Tatian (Address to the Greeks 19) and Eusebius (HE IV 16.7–8). Justin was tried, together with six companions, by the urban prefect Junius Rusticus, and was beheaded. Though the precise year of his death is uncertain, it can reasonably be dated by the prefectoral term of Rusticus (who governed from 162 and 168). The martyrdom of Justin preserves the court record of the trial.

The Prefect Rusticus says: Approach and sacrifice, all of you, to the gods. Justin says: No one in his right mind gives up piety for impiety. The Prefect Rusticus says: If you do not obey, you will be tortured without mercy. Justin replies: That is our desire, to be tortured for Our Lord, Jesus Christ, and so to be saved, for that will give us salvation and firm confidence at the more terrible universal tribunal of Our Lord and Saviour. And all the martyrs said: Do as you wish; for we are Christians, and we do not sacrifice to idols. The Prefect Rusticus read the sentence: Those who do not wish to sacrifice to the gods and to obey the emperor will be scourged and beheaded according to the laws. The holy martyrs glorifying God betook themselves to the customary place, where they were beheaded and consummated their martyrdom confessing their Saviour.

The church of St. John the Baptist in Sacrofano, a few miles north of Rome, claims to have his relics.

The Church of the Jesuits in Valletta, Malta, founded by papal decree in 1592 also boasts relics of this second century Saint.

A case is also made that the relics of St. Justin are buried in Annapolis, Maryland. During a period of unrest in Italy, a noble family in possession of his remains sent them in 1873 to a priest in Baltimore for safekeeping. They were displayed in St. Mary's Church for a period of time before they were again locked away for safekeeping. The remains were rediscovered and given a proper burial at St. Mary's, with Vatican approval, in 1989.

Relics of St. Justin and other early Church martyrs can be found in the lateral altar dedicated to St. Anne and St. Joachim at the Jesuit's Church in Valletta, Malta.

Relics of St. Justin and other early Church martyrs can be found in the lateral altar dedicated to St. Anne and St. Joachim at the Jesuit's Church in Valletta, Malta.

In 1882 Pope Leo XIII had a Mass and an Office composed for his feast day, which he set at 14 April, one day after the date of his death as indicated in the Martyrology of Florus; but since this date quite often falls within the main Paschal celebrations, the feast was moved in 1968 to 1 June, the date on which he has been celebrated in the Byzantine Rite since at least the 9th century.

Justin is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 1 June.

Writings

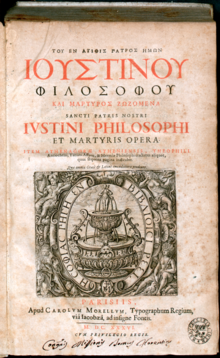

Iustini Philosophi et martyris Opera (1636)

Iustini Philosophi et martyris Opera (1636)

The earliest mention of Justin is found in the Oratio ad Graecos by Tatian who, after calling him "the most admirable Justin", quotes a saying of his and says that the Cynic Crescens laid snares for him. Irenaeus speaks of Justin's martyrdom and of Tatian as his disciple. Irenaeus quotes Justin twice and shows his influence in other places. Tertullian, in his Adversus Valentinianos, calls Justin a philosopher and a martyr and the earliest antagonist of heretics. Hippolytus and Methodius of Olympus also mention or quote him. Eusebius of Caesarea deals with him at some length, and names the following works:

- The First Apology addressed to Antoninus Pius, his sons, and the Roman Senate;

- A Second Apology of Justin Martyr addressed to the Roman Senate;

- The Discourse to the Greeks, a discussion with Greek philosophers on the character of their gods;

- An Hortatory Address to the Greeks (known now not to have been written by Justin);

- A treatise On the Sovereignty of God, in which he makes use of pagan authorities as well as Christian;

- A work entitled The Psalmist;

- A treatise in scholastic form On the Soul; and

- The Dialogue with Trypho.

Eusebius implies that other works were in circulation; from St Irenaeus he knows of the apology "Against Marcion," and from Justin's "Apology" of a "Refutation of all Heresies ". Epiphanius and St Jerome mention Justin.

Rufinus borrows from his Latin original of Hadrian's letter.

Medieval spurious works

After Rufinus, Justin was known mainly from St Irenaeus and Eusebius or from spurious works. A considerable number of other works are given as Justin's by Arethas, Photius, and other writers, but this attribution is now generally admitted to be spurious. The Expositio rectae fidei has been assigned by Draseke to Apollinaris of Laodicea, but it is probably a work of as late as the 6th century. The Cohortatio ad Graecos has been attributed to Apollinaris of Laodicea, Apollinaris of Hierapolis, as well as others. The Epistola ad Zenam et Serenum, an exhortation to Christian living, is dependent upon Clement of Alexandria, and is assigned by Pierre Batiffol to the Novatian Bishop Sisinnius (c. 400). The extant work under the title "On the Sovereignty of God" does not correspond with Eusebius' description of it, though Harnack regards it as still possibly Justin's, and at least of the 2nd century. The author of the smaller treatise To the Greeks cannot be Justin, because he is dependent on Tatian; Harnack places it between 180 and 240.

Parisinus graecus 450

After this medieval period in which no authentic works of Justin Martyr were in widespread circulation, a single codex containing the complete works of Justin Martyr was discovered and purchased by Guillaume Pellicier, around 1540 in Venice. Pellicier sent it to the Bibliothèque nationale de France where it remains today under the catalog number Parisinus graecus 450. This codex was completed on 11 September 1364 somewhere in the Byzantine Empire. The name of the scribe is unknown, although Manuel Kantakouzenos has been suggested as patron. Internal textual evidence shows that multiple older manuscripts were used to create this one, which strongly suggests that it must have originated in a major population center like Mistra, since libraries holding Justin Martyr were already rare by 1364. Other partial medieval manuscripts have been shown to be copies of this one. The editio princeps was published by Robert Estienne in 1551.

Dialogue with Trypho

The Dialogue is a later work than the First Apology; the date of composition of the latter, judging from the fact that it was addressed to Antoninus Pius and his adopted sons Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, must fall between 147 and 161. In the Dialogue with Trypho, after an introductory section, Justin undertakes to show that Christianity is the new law for all men.

Justin's dialogue with Trypho is unique in that he provides information on tensions between Jewish and Gentile believers in Jesus of the second century (Dial. 47:2–3) and in acknowledging the existence of a range, and a variety, of attitudes toward the beliefs and traditions of the Jewish believers in Jesus.

On the Resurrection

| This section does not cite any sources. (December 2015) |

The treatise On the Resurrection exists in extensive fragments that are preserved in the Sacra parallela. The fragments begin with the assertion that the truth, and God the author of truth, need no witness, but that as a concession to the weakness of men it is necessary to give arguments to convince those who gainsay it. It is then shown, after a denial of unfounded deductions, that the resurrection of the body is neither impossible nor unworthy of God, and that the evidence of prophecy is not lacking for it. Another fragment takes up the positive proof of the resurrection, adducing that of Christ and of those whom he recalled to life. In yet another fragment the resurrection is shown to be that of what has gone down, i.e., the body; the knowledge concerning it is the new doctrine, in contrast to that of the old philosophers. The doctrine follows from the command to keep the body in moral purity.

The authenticity of the treatise is not so generally accepted as are Justin's other works. Even so, earlier than the Sacra parallela, it is referred to by Procopius of Gaza (c. 465–528). Methodius appeals to Justin in support of his interpretation of 1 Corinthians 15:50 in a way that makes it natural to assume the existence of a treatise on the subject, to say nothing of other traces of a connection in thought both here in Irenaeus (V., ii.-xiii. 5) and in Tertullian, where it is too close to be anything but a conscious following of the Greek. The Against Marcion is lost, as is the Refutation of all Heresies to which Justin himself refers in Apology, i. 26; Hegesippus, besides perhaps Irenaeus and Tertullian, seems to have used it.

Role within the Church

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

Flacius discovered "blemishes" in Justin's theology, which he attributed to the influence of pagan philosophers; and in modern times Semler and S.G. Lange have made him out a thorough Hellene, while Semisch and Otto defend him from this charge.

In opposition to the school of Ferdinand Christian Baur, who considered him a Jewish Christian, Albrecht Ritschl has argued that it was precisely because he was a Gentile Christian that he did not fully understand the Old Testament foundation of Paul's teaching, and explained in this way the modified character of his Paulinism and his legal mode of thought.

Engelhardt has attempted to extend this line of treatment to Justin's entire theology, and to show that his conceptions of God, of free will and righteousness, of redemption, grace, and merit prove the influence of the cultivated Greek pagan world of the 2nd century, dominated by the Platonic and Stoic philosophy. But he admits that Justin is a Christian in his unquestioning adherence to the Church and its faith, his unqualified recognition of the Old Testament, and his faith in Christ as the Son of God the Creator, made manifest in the flesh, crucified, and risen, through which belief he succeeds in getting away from the dualism of both pagan and Gnostic philosophy.

Justin was confident that his teaching was that of the Church at large. He knows of a division among the orthodox only on the question of the millennium and on the attitude toward the milder Jewish Christianity, which he personally is willing to tolerate as long as its professors in their turn do not interfere with the liberty of the Gentile converts; his millenarianism seems to have no connection with Judaism, but he believes firmly in a millennium, and generally in the Christian eschatology.

Opposition to Judaism was common among church leaders in his day, however Justin Martyr was hostile towards Jewry and regarded Jews as an accursed people. His anti-Judaic polemics have been cited as an origin of Christian antisemitism. However his views elaborated in the Dialogue with Trypho were comparatively tame to those of John Chrysostom and others.

Christology

Justin, like others, thought that the Greek philosophers had derived, if not borrowed, the most essential elements of truth found in their teaching from the Old Testament. But at the same time he adopted the Stoic doctrine of the "seminal word," and so philosophy was to him an operation of the Word—in fact, through his identification of the Word with Christ, it was brought into immediate connection with him.

Thus he does not hesitate to declare that Socrates and Heraclitus were Christians (Apol., i. 46, ii. 10). His aim was to emphasize the absolute significance of Christ, so that all that ever existed of virtue and truth may be referred to him. The old philosophers and law-givers had only a part of the Logos, while the whole appears in Christ.

While the gentile peoples, seduced by devils, had deserted the true God for idols, the Jews and Samaritans possessed the revelation given through the prophets and awaited the Messiah. However, the law, while containing commandments intended to promote the true fear of God, had other prescriptions of a purely pedagogic nature, which necessarily ceased when Christ, their end, appeared; of such temporary and merely relative regulations were circumcision, animal sacrifices, the Sabbath, and the laws as to food. Through Christ, the abiding law of God has been fully proclaimed. In his character, as the teacher of the new doctrine and promulgator of the new law, lies the essential nature of his redeeming work.

The idea of an economy of grace, of a restoration of the union with God which had been destroyed by sin, is not foreign to him. It is noteworthy that in the "Dialogue" he no longer speaks of a "seed of the Word" in every man, and in his non-apologetic works the emphasis is laid upon the redeeming acts of the life of Christ rather than upon the demonstration of the reasonableness and moral value of Christianity, though the fragmentary character of the latter works makes it difficult to determine exactly to what extent this is true and how far the teaching of Irenaeus on redemption is derived from him.

The 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia notes that scholars have differed on whether Justin's writings on the nature of God were meant to express his firm opinion on points of doctrine, or to speculate on these matters. Specific points Justin addressed include that the Logos is "numerically distinct from the Father" though "born of the very substance of the Father," and that "through the Word, God has made everything." Justin used the metaphor of fire to describe the Logos as spreading like a flame, rather than "dividing" the substance of the Father. He also defended the Holy Spirit as a member of the Trinity, as well as the birth of Jesus to Mary when she was a virgin. The Encyclopedia states that Justin places the genesis of the Logos as a voluntary act of the Father at the beginning of creation, noting that this is an "unfortunate" conflict with later Christian teachings.

Memoirs of the apostles

Justin Martyr, in his First Apology (c. 155) and Dialogue with Trypho (c. 160), sometimes refers to written sources consisting of narratives of the life of Jesus and quotations of the sayings of Jesus as "memoirs of the apostles" (Greek: ἀπομνημονεύματα τῶν ἀποστόλων; transliteration: apomnêmoneúmata tôn apostólôn) and less frequently as gospels (Greek: εὐαγγέλιον; transliteration: euangélion) which, Justin says, were read every Sunday in the church at Rome (1 Apol. 67.3 – "and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are being read as long as it is allowable").

The designation "memoirs of the apostles" occurs twice in Justin's First Apology (66.3, 67.3–4) and thirteen times in the Dialogue, mostly in his interpretation of Psalm 22, whereas the term "gospel" is used only three times, once in 1 Apol. 66.3 and twice in the Dialogue. The single passage where Justin uses both terms (1 Apol. 66.3) makes it clear that "memoirs of the apostles" and "gospels" are equivalent, and the use of the plural indicates Justin's awareness of more than one written gospel. ("The apostles in the memoirs which have come from them, which are also called gospels, have transmitted that the Lord had commanded..."). Justin may have preferred the designation "memoirs of the apostles" as a contrast to the "gospel" of his contemporary Marcion to emphasize the connections between the historical testimony of the gospels and the Old Testament prophecies which Marcion rejected.

The origin of Justin's use of the name "memoirs of the apostles" as a synonym for the gospels is uncertain. Scholar David E. Aune has argued that the gospels were modeled after classical Greco-Roman biographies, and Justin's use of the term apomnemoneumata to mean all the Synoptic Gospels should be understood as referring to a written biography such as the Memorabilia of Xenophon because they preserve the authentic teachings of Jesus. However, scholar Helmut Koester has pointed out the Latin title "Memorabilia" was not applied to Xenophon's work until the Middle Ages, and it is more likely apomnemoneumata was used to describe the oral transmission of the sayings of Jesus in early Christianity. Papias uses a similar term meaning "remembered" (apomnemoneusen) when describing how Mark accurately recorded the "recollections of Peter", and Justin also uses it in reference to Peter in Dial. 106.3, followed by a quotation found only in the Gospel of Mark (Mk 3:16–17). Therefore, according to Koester, it is likely that Justin applied the name "memoirs of the apostles" analogously to indicate the trustworthy recollections of the apostles found in the written record of the gospels.

Justin expounded on the gospel texts as an accurate recording of the fulfillment of prophecy, which he combined with quotations of the prophets of Israel from the LXX to demonstrate a proof from prophecy of the Christian kerygma. The importance which Justin attaches to the words of the prophets, which he regularly quotes with the formula "it is written", shows his estimate of the Old Testament Scriptures. However, the scriptural authority he attributes to the "memoirs of the apostles" is less certain. Koester articulates a majority view among scholars that Justin considered the "memoirs of the apostles" to be accurate historical records but not inspired writings, whereas scholar Charles E. Hill, though acknowledging the position of mainstream scholarship, contends that Justin regarded the fulfillment quotations of the gospels to be equal in authority.

Composition

Scriptural sources

Gospels

Justin uses material from the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) in the composition of the First Apology and the Dialogue, either directly, as in the case of Matthew, or indirectly through the use of a gospel harmony, which may have been composed by Justin or his school. However, his use, or even knowledge, of the Gospel of John is uncertain. One possible reference to John is a saying that is quoted in the context of a description of Christian baptism (1 Apol. 61.4 – "Unless you are reborn, you cannot enter into the kingdom of heaven."). However, Koester contends that Justin obtained this saying from a baptismal liturgy rather than a written gospel. Justin's possible knowledge of John's gospel may be suggested by verbal similarities to John 3:4 directly after the discussion about the new birth ("Now, that it is impossible for those who have once been born to enter their mother's womb is manifest to all"). Justin also uses language very similar to that of John 1:20 and 1:28. Furthermore, by employing the term "memoirs of the apostles" and distinguishing them from the writings of their "followers", Justin must have been of the belief that at least two gospels were written by actual apostles.

Apocalypse

Justin does not quote from the Book of Revelation directly, yet he clearly refers to it, naming John as its author (Dial. 81.4 "Moreover also among us a man named John, one of the apostles of Christ, prophesied in a revelation made to him that those who have believed on our Christ will spend a thousand years in Jerusalem; and that hereafter the general and, in short, the eternal resurrection and judgment of all will likewise take place"). Scholar Brooke Foss Westcott notes that this reference to the author of the single prophetic book of the New Testament illustrates the distinction Justin made between the role of prophecy and fulfillment quotations from the gospels, as Justin does not mention any of the individual canonical gospels by name.

Letters

Reflecting his opposition to Marcion, Justin's attitude toward the Pauline epistles generally corresponds to that of the later Church. In Justin's works, distinct references are found to Romans, 1 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Colossians, and 2 Thessalonians, and possible ones to Philippians, Titus, and 1 Timothy. It seems likely that he also knew Hebrews and 1 John.

The apologetic character of Justin's habit of thought appears again in the Acts of his martyrdom, the genuineness of which is attested by internal evidence.

Testimony sources

According to scholar Oskar Skarsaune, Justin relies on two main sources for his proofs from prophecy that probably circulated as collections of scriptural testimonies within his Christian school. He refers to Justin's primary source for demonstrating scriptural proofs in the First Apology and parallel passages in the Dialogue as a "kerygma source". A second source, which was used only in the Dialogue, may be identical to a lost dialogue attributed to Aristo of Pella on the divine nature of the Messiah, the Dialogue of Jason and Papiscus (c. 140). Justin brings in biblical quotes verbatim from these sources, and he often appears to be paraphrasing his sources very closely, even in his interpretive remarks.

Justin occasionally uses the Gospel of Matthew directly as a source for Old Testament prophecies to supplement his testimony sources. However, the fulfillment quotations from these sources most often appear to be harmonizations of the gospels of Matthew and Luke. Koester suggests that Justin had composed an early harmony along the lines of his pupil Tatian's Diatesseron. However, the existence of a harmony independent of a collection of sayings for exposition purposes has been disputed by scholar Arthur Bellinzoni. The question of whether the harmonized gospel materials found in Justin's writings came from a preexisting gospel harmony or were assembled as part of an integral process of creating scriptural prooftexts is an ongoing subject of scholarly investigation.

"Kerygma source"

The following excerpt from 1 Apol. 33:1,4–5 (partial parallel in Dial. 84) on the annunciation and virgin birth of Jesus shows how Justin used harmonized gospel verses from Matthew and Luke to provide a scriptural proof of the messiahship of Jesus based on fulfillment of the prophecy of Isaiah 7:14.

And hear again how Isaiah in express words foretold that He should be born of a virgin; for he spoke thus: 'Behold, the virgin will conceive in the womb and bear a son, and they will say in his name, God with us' (Mt 1:23).

— 1 Apol. 33:1

...the power of God, coming down upon the virgin, overshadowed her and made her while yet a virgin to conceive (cf. Lk 1:35), and the angel of God proclaimed to her and said, 'Behold, you will conceive in the womb from the Holy Spirit and bear a son (Mt 1:20/Lk 1:31) and he will be called Son of the Most High (Lk 1:32). And you shall call his name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins (Mt 1:21),' as those who have made memoirs of all things about our savior Jesus Christ taught...

— 1 Apol. 33:4–5

According to Skarsaune, the harmonized gospel narratives of Matthew and Luke were part of a tradition already circulating within Justin's school that expounded on the life and work of Jesus as the Messiah and the apostolic mission. Justin then rearranged and expanded these testimonia to create his First Apology. The "kerygma source" of prooftexts (contained within 1 Apol. 31–53) is believed to have had a Two Parousias Christology, characterized by the belief that Jesus first came in humility, in fulfillment of prophecy, and will return in glory as the Messiah to the Gentiles. There are close literary parallels between the Christology of Justin's source and the Apocalypse of Peter.

Dialogue of Jason and Papiscus

The following excerpts from the Dialogue with Trypho of the baptism (Dial. 88:3,8) and temptation (Dial. 103:5–6) of Jesus, which are believed to have originated from the Dialogue of Jason and Papiscus, illustrate the use of gospel narratives and sayings of Jesus in a testimony source and how Justin has adopted these "memoirs of the apostles" for his own purposes.

And then, when Jesus had come to the river Jordan where John was baptizing, and when Jesus came down into the water, a fire was even kindled in the Jordan, and when He was rising up from the water, the Holy Spirit fluttered down upon Him in the form of a dove, as the apostles have written about this very Christ of ours.

— Dial. 88:3

And when Jesus came to the Jordan, and being supposed to be the son of Joseph the carpenter..., the Holy Spirit, and for man's sake, as I said before, fluttered down upon Him, and a voice came at the time out of the heavens – which was spoken also by David, when he said, impersonating Christ, what the Father was going to say to Him – 'You are My Son, this day I have begotten you'."

— Dial. 88:8

...the Devil himself,...[was] called serpent by Moses, the Devil by Job and Zachariah, and was addressed as Satanas by Jesus. This indicated that he had a compound name made up of the actions which he performed; for the word "Sata" in the Hebrew and Syrian tongue means "apostate", while "nas" is the word which means in translation "serpent", thus, from both parts is formed the one word "Sata-nas". It is narrated in the memoirs of the apostles that as soon as Jesus came up out of the river Jordan and a voice said to him: 'You are My Son, this day I have begotten you', this Devil came and tempted him, even so far as to exclaim: 'Worship me'; but Christ replied: 'Get behind me, Satanas, the Lord your God shall you worship, and Him only shall you serve'. For, since the Devil had deceived Adam, he fancied that he could in some way harm him also.

— Dial. 103:5–6

The quotations refer to the fulfillment of a prophecy of Psalm 2:7 found in the Western text-type of Luke 3:22. Justin's mention of the fire on the Jordan without comment suggests that he was relying on an intermediate source for these gospel quotations, and his literal interpretation of a pseudo-etymology of the Hebrew word Satan indicates a dependence on a testimony source with a knowledge of Hebrew, which was probably the Dialogue of Jason and Papiscus.

The Dialogue attributed to Aristo of Pella is believed to have furnished Justin with scriptural prooftexts on the divinity of the Messiah by combining a Wisdom Christology – Christ as the incarnation of preexistent Wisdom – with a Second Adam Christology – the first Adam was conquered by Satan, but this Fall of Man is reversed by Christ as the Second Adam who conquers Satan. This is implied in the pseudo-etymology in Dial. 103:5–6 linking the name of Satan to the "apostate-serpent". The Christology of the source is close to that of the Ascension of Isaiah.

Catechetical sources

Justin quotes many sayings of Jesus in 1 Apol. 15–17 and smaller sayings clusters in Dial. 17:3–4; 35:3; 51:2–3; and 76:4–7. The sayings are most often harmonizations of Matthew and Luke that appear to be grouped together topically and organized into sayings collections, including material that probably originated from an early Christian catechism.

The following example of an ethical teaching On Swearing Oaths in 1 Apol. 16:5 shows a combination of sayings material found in Matthew and the Epistle of James:

Do not swear at all (Mt 5:34). Let your Yes be Yes and your No be No (Jas 5:12). Everything beyond these is from evil (Mt 5:37).

The saying "Let your Yes be Yes and your No be No" from James 5:12 is interpolated into a sayings complex from Matthew 5:34,37. The text appears in a large number of Patristic quotations and twice in the Clementine Homilies (Hom. 3:55, 19:2). Thus, it is likely that Justin was quoting this harmonized text from a catechism.

The harmonization of Matthew and Luke is evident in the following quotations of Mt 7:22–23 and Lk 13:26–27, which are used by Justin twice, in 1 Apol. 16:11 and Dial. 76:5:

Many will say to me, 'Lord, Lord, did we not in your name eat and drink and do powerful deeds?' And then I shall say to them, 'go away from me, workers of lawlessness'.

Many will say to me on that day, 'Lord, Lord, did we not in your name eat and drink and prophecy and drive out demons?' And I shall say to them, 'go away from me'.

In both cases, Justin is using the same harmonized text of Matthew and Luke, although neither of the quotations includes the entire text of those gospel passages. The last phrase, "workers of lawlessness", has an exact parallel with 2 Clement 4:5. This harmonized text also appears in a large number of quotations by the Church Fathers. 1 Apol. 16:11 is part of a larger unit of sayings material in 1 Apol 16:9–13 which combines a warning against being unprepared with a warning against false prophets. The entire unit is a carefully composed harmony of parallel texts from Matthew and Luke. This unit is part of a larger collection of sayings found in 1 Apol. 15–17 that appear to have originated from a catechism used by Justin's school in Rome, which may have had a wide circulation. Justin excerpted and rearranged the catechetical sayings material to create Apol. 15–17 and parallel passages in the Dialogue.

Other sources

Justin includes a tract on Greek mythology in 1 Apol. 54 and Dial. 69 which asserts that myths about various pagan deities are imitations of the prophecies about Christ in the Old Testament. There is also a small tract in 1 Apol. 59–60 on borrowings of the philosophers from Moses, particularly Plato. These two tracts may be from the same source, which may have been an early Christian Apology.

Prophetic exegesis

Justin's writings constitute a storehouse of early interpretation of the prophetic Scriptures.

Belief in prophecy

The truth of the prophets, he declares, compels assent. He considered the Old Testament an inspired guide and counselor. He was converted by a Christian philosopher whom he paraphrased as saying:

- "There existed, long before this time, certain men more ancient than all those who are esteemed philosophers, both righteous and beloved by God, who spoke by the Divine Spirit, and foretold events which would take place, and which are now taking place. They are called prophets. These alone both saw and announced the truth to men, neither reverencing nor fearing any man. not influenced by a desire for glory, but speaking those things alone which they saw and which they heard, being filled with the Holy Spirit. Their writings are still extant, and he who has read them is very much helped in his knowledge of the beginning and end of things. . . And those events which have happened, and those which are happening, compel you to assent to the utterances made by them."

Then Justin told his own experience:

- "Straightway a flame was kindled in my soul; and a love of the prophets, and of those men who are friends of Christ, possessed me; and whilst revolving his words in my mind, I found this philosophy alone to be safe and profitable."

Fulfillment

Justin listed the following events as fulfillments of Bible prophecy:

- The prophecies concerning the Messiah, and the particulars of His life.

- The destruction of Jerusalem.

- The Gentiles accepting Christianity.

- Isaiah predicted that Jesus would be born of a virgin.

- Micah mentions Bethlehem as the place of His birth.

- Zechariah forecasts His entry into Jerusalem on the foal of an ass (a donkey).

Second Advent and Daniel 7

Justin connected the Second Advent with the climax of the prophecy of Daniel 7.

- "But if so great a power is shown to have followed and to be still following the dispensation of His suffering, how great shall that be which shall follow His glorious advent! For He shall come on the clouds as the Son of man, so Daniel foretold, and His angels shall come with Him. [Then follows Dan. 7:9–28.]"

Antichrist

The second advent Justin placed close upon the heels of the appearance of the "man of apostasy", i.e., the Antichrist.

Time, times, and a half

Daniel's "time, times, and a half", Justin believed, was nearing its consummation, when the Antichrist would speak his blasphemies against the Most High.

Eucharist

Justin's statements are some of the earliest Christian expressions on the Eucharist.

- "And this food is called among us Εὐχαριστία [the Eucharist] ... For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh."

Editions

Greek texts:

- P.Oxy.5129 (Egyptian Exploration Society, 4th century)

- Thirlby, S., London, 1722.

- Maran, P., Paris, 1742 (the Benedictine edition, reprinted in Migne, Patrologia Graeca, Vol. VI. Paris, 1857).

- Otto, J. C., Jena, 1842 (3d ed., 1876–1881).

- Krüger, G., Leipzig, 1896 (3d ed., Tübingen, 1915).

- In Die ältesten Apologeten, ed. G.J. Goodspeed, (Göttingen, 1914; reprint 1984).

- Iustini Martyris Dialogus cum Tryphone, ed Miroslav Marcovich (Patristische Texte und Studien 47, Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, 1997).

- Minns, Denis, and Paul Parvis. Justin, Philosopher and Martyr: Apologies. Edited by Henry Chadwick, Oxford Early Christian Texts. Oxford: OUP, 2009. (In addition to translating into English has a critical Greek text).

- Philippe Bobichon (ed.), Justin Martyr, Dialogue avec Tryphon, édition critique, introduction, texte grec, traduction, commentaires, appendices, indices, (Coll. Paradosis nos. 47, vol. I-II.) Editions Universitaires de Fribourg Suisse, (1125 pp.), 2003 online

English translations:

- Halton, TP and M Slusser, eds, Dialogue with Trypho, trans TB Falls, Selections from the Fathers of the Church, 3, (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press)

- Minns, Denis, & Paul Parvis. Justin, Philosopher and Martyr: Apologies. Edited by Henry Chadwick, Oxford Early Christian Texts. Oxford: OUP, 2009.

Georgian translation:

- "Sulieri Venakhi", II, Saint Justin Martyr's dialogue with Trypho the Jew, translated from Old Greek into Georgian, submitted with preface and comments by a monk Ekvtime Krupitski, Tbilisi Theological Academy, Tsalka, Sameba village, Cross Monastery, "Sulieri venakhi" Publishers, Tbilisi, 2019, ISBN 978-9941-8-1570-6

Literary references

- The Rector of Justin (1964), perhaps Louis Auchincloss's best-regarded novel, is the tale of a renowned headmaster of a New England prep school—similar to Groton—and how he came to found his institution. He chooses the name Justin Martyr for his Episcopal school. ("The school was named for the early martyr and scholar who tried to reconcile the thinking of the Greek philosophers with the doctrines of Christ. Not for Prescott [the headmaster] were the humble fishermen who had their faith and faith alone.")