Feastday: January 13

Patron: against snake bites

Death: 368

"They didn't know who they were." This is how Hilary summed up the problem with the Arian heretics of the fourth century.

Hilary, on the other hand, knew very well who he was -- a child of a loving God who had inherited eternal life through belief in the Son of God. He hadn't been raised as a Christian but he had felt a wonder at the gift of life and a desire to find out the meaning of that gift. He first discarded the approach of many people who around him, who believed the purpose of life was only to satisfy desires. He knew he wasn't a beast grazing in a pasture. The philosophers agreed with him. Human beings should rise above desires and live a life of virtue, they said. But Hilary could see in his own heart that humans were meant for even more than living a good life.

If he didn't lead a virtuous life, he would suffer from guilt and be unhappy. His soul seemed to cry out that wasn't enough to justify the enormous gift of life. So Hilary went looking for the giftgiver. He was told many things about the divine -- many that we still hear today: that there were many Gods, that God didn't exist but all creation was the result of random acts of nature, that God existed but didn't really care for his creation, that God was in creatures or images. One look in his own soul told him these images of the divine were wrong. God had to be one because no creation could be as great as God. God had to be concerned with God's creation -- otherwise why create it?

At that point, Hilary tells us, he "chanced upon" the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures. When he read the verse where God tells Moses "I AM WHO I AM" (Exodus 3:14), Hilary said, "I was frankly amazed at such a clear definition of God, which expressed the incomprehensible knowledge of the divine nature in words most suited to human intelligence." In the Psalms and the Prophets he found descriptions of God's power, concern, and beauty. For example in Psalm 139, "Where shall I go from your spirit?", he found confirmation that God was everywhere and omnipotent.

But still he was troubled. He knew the giftgiver now, but what was he, the recipient of the gift? Was he just created for the moment to disappear at death? It only made sense to him that God's purpose in creation should be "that what did not exist began to exist, not that what had begun to exist would cease to exist." Then he found the Gospels and read John's words including "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God..." (John 1:1-2). From John he learned of the Son of God and how Jesus had been sent to bring eternal life to those who believed. Finally his soul was at rest. "No longer did it look upon the life of this body as troublesome or wearisome, but believed it to be what the alphabet is to children... namely, as the patient endurance of the present trials of life in order to gain a blissful eternity." He had found who he was in discovering God and God's Son Jesus Christ.

After becoming a Christian, he was elected bishop of Poitiers in what is now France by the laity and clergy. He was already married with one daughter named Apra.

Not everyone at that time had the same idea of who they were. The Arians did not believe in the divinity of Christ and the Arians had a lot of power including the support of the emperor Constantius. This resulted in many persecutions. When Hilary refused to support their condemnation of Saint Athanasius he was exiled from Poitiers to the East in 356. The Arians couldn't have had a worse plan -- for themselves.

Hilary really had known very little of the whole Arian controversy before he was banished. Perhaps he supported Athanasius simply because he didn't like their methods. But being exiled from his home and his duties gave him plenty of time to study and write. He learned everything he could about what the Arians said and what the orthodox Christians answered and then he began to write. "Although in exile we shall speak through these books, and the word of God, which cannot be bound, shall move about in freedom." The writings of his that still exist include On the Trinity, a commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, and a commentary on the Psalms. He tells us about the Trinity, "For one to attempt to speak of God in terms more precise than he himself has used: -- to undertake such a thing is to embark upon the boundless, to dare the incomprehensible. He fixed the names of His nature: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Whatever is sought over and above this is beyond the meaning of words, beyond the limits of perception, beyond the embrace of understanding."

After three years the emperor kicked him back to Poitiers, because, we are told by Sulpicius Severus, the emperor was tired of having to deal with the troublemaker, "a sower of discord an a disturber of the Orient." But no one told Hilary he had to go straight back to his home and so he took a leisurely route through Greece and Italy, preaching against the Arians as he went.

In the East he had also heard the hymns used by Arians and orthodox Christians as propaganda. These hymns were not based on Scripture as Western hymns but full of beliefs about God. Back at home, Hilary started writing hymns of propaganda himself to spread the faith. His hymns are the first in the West with a known writer.

Some of use may wonder at all the trouble over what may seem only words to us now. But Hilary wasn't not fighting a war of words, but a battle for the eternal life of the souls who might hear the Arians and stop believing in the Son of God, their hope of salvation.

The death of Constantius in 361 ended the persecution of the orthodox Christians. Hilary died in 367 or 368 and was proclaimed a doctor of the Church in 1851.

In His Footsteps:In Exodus, the Prophets, and the Gospel of John, Hilary found his favorite descriptions of God and God's relationship to us. What verses of Scripture describe God best for you? If you aren't familiar with Scripture, look up the verses that Hilary found. What do they mean to you?

Prayer:Saint Hilary of Poitiers, instead of being discouraged by your exile, you used your time to study and write. Help us to bring good out of suffering and isolation in our own lives and see adversity as an opportunity to learn about or share our faith. Amen

Bishop of Poitiers

Hilary of Poitiers (Latin: Hilarius; c. 310 – c. 367) was Bishop of Poitiers and a Doctor of the Church. He was sometimes referred to as the "Hammer of the Arians" (Malleus Arianorum) and the "Athanasius of the West", His name comes from the Latin word for happy or cheerful. In addition to his important work as bishop, Hilary was married and the father of Abra of Poitiers, a nun and saint who became known for her charity. His optional memorial in the General Roman Calendar is 13 January. In the past, when this date was occupied by the Octave Day of the Epiphany, his feast day was moved to 14 January.

Early life

Hilary was born at Poitiers either at the end of the 3rd or beginning of the 4th century A.D. His parents were pagans of distinction. He received a good pagan education, which included a high level of Greek. He studied, later on, the Old and New Testament writings, with the result that he abandoned his Neo-Platonism for Christianity, and with his wife and his daughter (traditionally named Saint Abra), was baptized and received into the Church.

The Christians of Poitiers so respected Hilary that about 350 or 353, they unanimously elected him their bishop. At that time Arianism threatened to overrun the Western Church; Hilary undertook to repel the disruption. One of his first steps was to secure the excommunication, by those of the Gallican hierarchy who still remained orthodox Christians, of Saturninus, the Arian Bishop of Arles, and of Ursacius of Singidunum and Valens of Mursa, two of his prominent supporters.

About the same time, Hilary wrote to Emperor Constantius II a remonstrance against the persecutions by which the Arians had sought to crush their opponents (Ad Constantium Augustum liber primus, of which the most probable date is 355). Other Historians refer to this first book to Constantius as "Book Against Valens," of which only fragments are extant. His efforts did not succeed at first, for at the synod of Biterrae (Béziers), summoned by the emperor in 356 with the professed purpose of settling the longstanding dispute, an imperial rescript banished the new bishop, along with Rhodanus of Toulouse, to Phrygia.

Hilary spent nearly four years in exile, although the reasons for this banishment remain obscure. The traditional explanation is that Hilary was exiled for refusing to subscribe to the condemnation of Athanasius and the Nicene faith. More recently several scholars have suggested that political opposition to Constantius and support of the usurper Silvanus may have led to Hilary's exile.

In exile

While in Phrygia, however, he continued to govern his diocese, as well as writing two of the most important of his contributions to dogmatic and polemical theology: the De synodis or De fide Orientalium, an epistle addressed in 358 to the Semi-Arian bishops in Gaul, Germania and Britain, analyzing the views of the Eastern bishops on the Nicene controversy. In reviewing the professions of faith of the Oriental bishops in the Councils of Ancyra, Antioch, and Sirmium, he sought to show that sometimes the difference between certain doctrines and orthodox beliefs was rather in the words than in the ideas, which led to his counseling the bishops of the West to be more reserved in their condemnation.

The De trinitate libri XII, composed in 359 and 360, was the first successful expression in Latin of that Council's theological subtleties originally elaborated in Greek. Although some members of Hilary's own party thought the first had shown too great a forbearance towards the Arians, Hilary replied to their criticisms in the Apologetica ad reprehensores libri de synodis responsa. Hilary was a firm guardian of the Trinity as taught by the Western church, and therefore saw the foreseen Antichrist in those who repudiated the divinity of the Son and thought Him to be but a created Being. "Hence also they who deny that Christ is the Son of God must have Antichrist for their Christ," was the way he stated it.

In his classic introduction to the works of Hilary, Watson summarizes Hilary's points:

- “They were the forerunners of Antichrist. . . . They bear themselves not as bishops of Christ but as priests of Antichrist. This is not random abuse, but sober recognition of the fact, stated by St. John, that there are many Antichrists. For these men assume the cloak of piety, and pretend to preach the Gospel, with the one object of inducing others to deny Christ. It was the misery and folly of the day that men endeavoured to promote the cause of God by human means and the favour of the world. Hilary asks bishops, who believe in their office, whether the Apostles had secular support when by their preaching they converted the greater part of mankind. . . .

- “The Church seeks for secular support, and in so doing insults Christ by the implication that His support is insufficient. She in her turn holds out the threat of exile and prison. It was her endurance of these that drew men to her; now she imposes her faith by violence. She craves for favours at the hand of her communicants; once it was her consecration that she braved the threatenings of persecutors. Bishops in exile spread the Faith; now it is she that exiles bishops. She boasts that the world loves her; the world's hatred was the evidence that she was Christ's. . . . The time of Antichrist, disguised as an angel of light, has come. The true Christ is hidden from almost every mind and heart. Antichrist is now obscuring the truth that he may assert falsehood hereafter."

Constantius II coin.

Constantius II coin.Hilary also attended several synods during his time in exile, including the council at Seleucia (359) which saw the triumph of the homoion party and the forbidding of all discussion of the divine substance. In 360, Hilary tried unsuccessfully to secure a personal audience with Constantius, as well as to address the council which met at Constantinople in 360. When this council ratified the decisions of Ariminum and Seleucia, Hilary responded with the bitter In Constantium, which attacked the Emperor Constantius as Antichrist and persecutor of orthodox Christians. Hilary's urgent and repeated requests for public debates with his opponents, especially with Ursacius and Valens, proved at last so inconvenient that he was sent back to his diocese, which he appears to have reached about 361, within a very short time of the accession of Emperor Julian.

Later life

On returning to his diocese in 361, Hilary spent most of the first two or three years trying to persuade the local clergy that the homoion confession was merely a cover for traditional Arian subordinationism. Thus, a number of synods in Gaul condemned the creed promulgated at Council of Ariminium (359).

In about 360 or 361, with Hilary's encouragement, Martin, the future bishop of Tours, founded a monastery at Ligugé in his diocese.

In 364, Hilary extended his efforts once more beyond Gaul. He impeached Auxentius, bishop of Milan, a man high in the imperial favour, as heterodox. Emperor Valentinian I accordingly summoned Hilary to Milan to there maintain his charges. However, the supposed heretic gave satisfactory answers to all the questions proposed. Hilary denounced Auxentius as a hypocrite as he himself was ignominiously expelled from Milan. Upon returning home, Hilary in 365, published the Contra Arianos vel Auxentium Mediolanensem liber, describing his unsuccessful efforts against Auxentius. He also (but perhaps at a somewhat earlier date) published the Contra Constantium Augustum liber, accusing the lately deceased emperor as having been the Antichrist, a rebel against God, "a tyrant whose sole object had been to make a gift to the devil of that world for which Christ had suffered."

According to Jerome, Hilary died in Poitiers in 367.

Writings

Opera omnia (1523)

Opera omnia (1523)

Recent research has distinguished between Hilary's thought before his period of exile in Phrygia under Constantius and the quality of his later major works. While Hilary closely followed the two great Alexandrians, Origen and Athanasius, in exegesis and Christology respectively, his work shows many traces of vigorous independent thought.

Exegetical

Among Hilary's earliest writings, completed some time before his exile in 356, is his Commentarius in Evangelium Matthaei, an allegorical exegesis of the first Gospel. This is the first Latin commentary on Matthew to have survived in its entirety. Hilary's commentary was strongly influenced by Tertullian and Cyprian, and made use of several classical writers, including Cicero, Quintilian, Pliny and the Roman historians.

Hilary's expositions of the Psalms, Tractatus super Psalmos, largely follow Origen, and were composed some time after Hilary returned from exile in 360. Since Jerome found the work incomplete, no one knows whether Hilary originally commented on the whole Psalter. Now extant are the commentaries on Psalms 1, 2, 9, 13, 14, 51–69, 91, and 118–150.

The third surviving exegetical writing by Hilary is the Tractatus mysteriorum, preserved in a single manuscript first published in 1887.

Because Augustine cites part of the commentary on Romans as by "Sanctus Hilarius" it has been ascribed by various critics at different times to almost every known Hilary.

Theological

Hilary's major theological work was the twelve books now known as De Trinitate. This was composed largely during his exile, though perhaps not completed until his return to Gaul in 360.

Another important work is De synodis, written early in 359 in preparation for the councils of Ariminium and Seleucia.

Historical works and hymns

Various writings comprise Hilary's 'historical' works. These include the Liber II ad Constantium imperatorem, the Liber in Constantium inperatorem, Contra Arianos vel Auxentium Mediolanensem liber, and the various documents relating to the Arian controversy in Fragmenta historica.

Some consider Hilary as the first Latin Christian hymn writer, because Jerome said Hilary produced a liber hymnorum. Three hymns are attributed to him, though none are indisputable.

Reputation and veneration

Hilary is the pre-eminent Latin writer of the 4th century (before Ambrose). Augustine of Hippo called him "the illustrious doctor of the churches", and his works continued to be highly influential in later centuries. Venantius Fortunatus wrote a vita of Hilary by 550, but few now consider it reliable. More trustworthy are the notices in Saint Jerome (De vir. illus. 100), Sulpicius Severus (Chron. ii. 39–45) and in Hilary's own writings. Pope Pius IX formally recognized him as Universae Ecclesiae Doctor in 1851.

In the Roman calendar of saints, Hilary's feast day is on 13 January, 14 January in the pre-1970 form of the calendar. The spring terms of the English and Irish Law Courts and Oxford and Dublin Universities are called the Hilary term since they begin on approximately this date. Some consider Saint Hilary of Poitiers the patron saint of lawyers.

Hilary is remembered in the Anglican Communion with a Lesser Festival on 13 January.

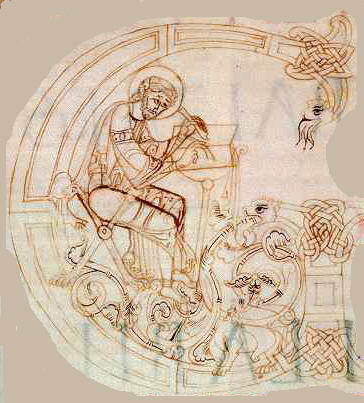

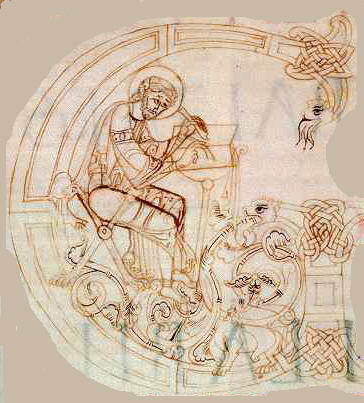

Iconography

From his writing St. Hilary's symbol came to be three books and a quill pen.

Dedications

Sulpicius Severus' Vita Sancti Martini led to a cult of Saint Hilary as well as of St. Martin of Tours which spread early to western Britain. The villages of St Hilary in Cornwall and Glamorgan and that of Llanilar in Ceredigion bear his name.

In France most dedications to Saint Hilary are styled "Saint-Hilaire" and lie west (and north) of the Massif Central; the cult in this region eventually extended to Canada.

In northwest Italy the church of Sant’Ilario at Casale Monferrato was dedicated to St. Hilary as early as 380.