Feastday: June 9

Death: 373?

"I was born in the way of truth: though my childhood was unaware of the greatness of the benefit, I knew it when trial came."

Ephrem (or Eprhaim) the Syrian left us hundreds of hymns and poems on the faith that inflamed and inspired the whole Church, but few facts about his own inspiring life.

Most historians infer from the lines quoted above that Ephrem was born into a Christian family -- although not baptized until an adult (the trial or furnace), which was common at the time. Other than that little is known about his birth and youth although many guess he was born in the early fourth century in Mesopotamia, possibly in Nisibis where he spent most of his adult life.

"He Who created two great lights, chose for Himself these three Lights, and set them in the three dark seasons of siege that have been."

Ephrem served as teacher, and possibly deacon, under four bishops of Nisibis, Jacob, Babu, Vologeses, and Abraham. The first three he describes in the hymn quoted above written while Vologeses was still alive. As the verse states, Ephrem did not live in easy times in Nisibis.

"I have chanced upon weeds, my brothers, That wear the color of wheat, To choke the good seed."

According to tradition, Ephrem began to write hymns in order to counteract the heresies that were rampant at that time. For those who think of hymns simply as the song at the end of Mass that keeps us from leaving the church early, it may come as a surprise that Ephrem and others recognized and developed the power of music to get their points across. Tradition tells us that Ephrem heard the heretical ideas put into song first and in order to counteract them made up his own hymns. In the one below, his target is a Syrian heretic Bardesan who denied the truth of the Resurrection:

"How he blasphemes justice, And grace her fellow-worker. For if the body was not raised, This is a great insult against grace, To say grace created the body for decay; And this is slander against justice, to say justice sends the body to destruction."

The originality, imagery, and skill of his hymns captured the hearts of the Christians so well, that Ephrem is given credit for awakening the Church to the important of music and poetry in spreading and fortifying the faith.

Ephrem's home was in physical as well as spiritual danger. Nisibis, a target of Shapur II, the King of Persia, was besieged by him three times. During the third siege in in 350, Shapur's engineers turned the river out of its course in order to flood the city as Ephrem describes (speaking as Nisibis):

"All kinds of storms trouble me -- and you have been kinder to the Ark: only waves surrounded it, but ramps and weapons and waves surround me... O Helmsman of the Ark, be my pilot on dry land! You gave the Ark rest on the haven of a mountain, give me rest in the haven of my walls."

The flood, however, turned the tide against Shapur. When he tried to invade he found his army obstructed by the very waters and ruin he had caused. The defenders of the city, including Ephrem, took advantage of the chaos to ambush the invaders and drive them out.

"He has saved us without wall, and taught us that He is our wall: He has saved us without king and made us know that is our king: He has saved us, in each and all, and showed us that He is All."

In the end, however, Nisibis lost. When Shapur defeated the Roman emperor Jovian, he demanded the city as part of the treaty. Jovian not only gave him the city but agreed to force the Christians to leave Nisibis. Probably in his fifties or sixties at that time, Ephrem was one of the refugees who fled the city in 363.

Sometime in 364 he settled as a solitary ascetic on Mount Edessa, at Edessa (what is now Urfa) 100 miles east of his home.

"The soul is your bride, the body is your bridal chamber..."

In the time before monks and monasteries, many devout Christians drawn to a religious life dedicated themselves as ihidaya (single and single-minded followers of Christ). As one of these Eprhem lived an ascetic, celibate life for his last years.

Heresy and danger followed him to Edessa. The Arian Emperor Valens camped outside of Edessa threatening to kill all the Christian inhabitants if they did not submit. But Valens was the one forced to give up in the face of the courage and steadfastness of the Edessans (fortified by Ephrem's hymns):

"The doors of her homes Edessa Left open when she went forth With the pastor to the grave, to die, And not depart from her faith. Let the city and fort and building And houses be yielded to the king; Our goods and our gold let us leave; So we part not from our faith!"

Tradition tells us that during the famine that hit Edessa in 372, Ephrem was horrified to learn that some citizens were hoarding food. When he confronted them, he received the age-old excuse that they couldn't find a fair way or honest person to distribute the food. Ephrem immediately volunteered himself and it is a sign of how respected he was that no one was able to argue with this choice. He and his helpers worked diligently to get food to the needy in the city and the surrounding area.

The famine ended in a year of abundant harvest the following year and Ephrem died shortly thereafter, as we are told, at an advanced age. We do not know the exact date or year of his death but June 9, 373 is accepted by many. Ephrem relates in his dying testament a childhood vision of his life that he gloriousl fulfilled:

"There grew a vine-shoot on my tongue: and increased and reached unto heaven, And it yielded fruit without measure: leaves likewise without number. It spread, it stretched wide, it bore fruit: all creation drew near, And the more they were that gathered: the more its clusters abounded. These clusters were the Homilies; and these leaves the Hymns. God was the giver of them: glory to Him for His grace! For He gave to me of His good pleasure: from the storehouse of His treasures."

Has a song ever moved you so much that it changed or challenged your faith or lifestyle -- for good or bad? How do you feel about the music you sing during liturgy? Put your whole heart and soul into the hymns you sing next. Listen to the words and let them speak to you.

Prayer:Saint Ephrem, sometimes we treat the power of song lightly. Help us to open our hearts and souls to the inspiration of the Holy Spirit given us through music. Amen .

4th century Syrian deacon, hymnographer and theologian| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

Subdivisions

|

Noncanonical/Independent churches

|

History and theology

|

Liturgy and practices

|

Major figures

|

Related topics

|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

|

Background

|

Organization

|

Autocephalous jurisdictionsAutocephalous Churches who are officially part of the communion:

Autocephaly recognized universally de facto, by some Autocephalous Churches de jure:

Autocephaly recognized by Constantinople and 3 other Autocephalous Churches:

|

Noncanonical jurisdictions

|

Ecumenical councils

|

History

|

Theology

|

Liturgy and worship

|

Liturgical calendar

|

Major figures

|

Other topics

|

|

Ephrem the Syrian (Classical Syriac: ܡܪܝ ܐܦܪܝܡ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ, romanized: Mār ʾAp̄rêm Sūryāyā, Classical Syriac pronunciation: [mɑr ʔafˈrem surˈjɑjɑ]; Koinē Greek: Ἐφραίμ ὁ Σῦρος, romanized: Efrém o Sýros; Latin: Ephraem Syrus; c. 306 – 373), also known as Saint Ephrem, Ephrem of Edessa or Aprem of Nisibis, was a prominent Christian theologian and writer, who is revered as one of the most notable hymnographers of Eastern Christianity. He was born in Nisibis, served as a deacon and later lived in Edessa.

Ephrem is venerated as a saint by all traditional Churches. He is especially revered in Syriac Christianity, both in East Syriac tradition and West Syriac tradition, and also counted as a Venerable Father (i.e., a sainted Monk) in the Eastern Orthodox Church. His feast day is celebrated on 28 January and on the Saturday of the Venerable Fathers. He was declared a Doctor of the Church in the Roman Catholic Church in 1920.

Ephrem wrote a wide variety of hymns, poems, and sermons in verse, as well as prose exegesis. These were works of practical theology for the edification of the Church in troubled times. So popular were his works, that, for centuries after his death, Christian authors wrote hundreds of pseudepigraphal works in his name. He has been called the most significant of all of the fathers of the Syriac-speaking church tradition.

Life

Ephrem was born around the year 306 in the city of Nisibis (modern Nusaybin, Turkey), in the Roman province of Mesopotamia, that was recently acquired by the Roman Empire. Internal evidence from Ephrem's hymnody suggests that both his parents were part of the growing Christian community in the city, although later hagiographers wrote that his father was a pagan priest. In those days, religious culture in the region of Nisibis included local polytheism, Judaism and several varieties of the Early Christianity. Majority of population spoke Aramaic language, while Greek and Latin were languages of administration. The city had a complex ethnic composition, consisted of "Assyrian, Arabs, Greeks, Jews, Parthians, Romans, and Iranians".

Jacob, the second bishop of Nisibis, was appointed in 308, and Ephrem grew up under his leadership of the community. Jacob of Nisibis is recorded as a signatory at the First Council of Nicea in 325. Ephrem was baptized as a youth and almost certainly became a son of the covenant, an unusual form of Syriac proto-monasticism. Jacob appointed Ephrem as a teacher (Syriac malp̄ānâ, a title that still carries great respect for Syriac Christians). He was ordained as a deacon either at his baptism or later. He began to compose hymns and write biblical commentaries as part of his educational office. In his hymns, he sometimes refers to himself as a "herdsman" (ܥܠܢܐ, ‘allānâ), to his bishop as the "shepherd" (ܪܥܝܐ, rā‘yâ), and to his community as a 'fold' (ܕܝܪܐ, dayrâ). Ephrem is popularly credited as the founder of the School of Nisibis, which, in later centuries, was the centre of learning of the Church of the East.

Newly excavated Church of Saint Jacob of Nisibis, where Ephrem taught and ministered

Newly excavated Church of Saint Jacob of Nisibis, where Ephrem taught and ministered

In 337, Emperor Constantine I, who had legalised and promoted the practice of Christianity in the Roman Empire, died. Seizing on this opportunity, Shapur II of Persia began a series of attacks into Roman North Mesopotamia. Nisibis was besieged in 338, 346 and 350. During the first siege, Ephrem credits Bishop Jacob as defending the city with his prayers. In the third siege, of 350, Shapur rerouted the River Mygdonius to undermine the walls of Nisibis. The Nisibenes quickly repaired the walls while the Persian elephant cavalry became bogged down in the wet ground. Ephrem celebrated what he saw as the miraculous salvation of the city in a hymn that portrayed Nisibis as being like Noah's Ark, floating to safety on the flood.

One important physical link to Ephrem's lifetime is the baptistery of Nisibis. The inscription tells that it was constructed under Bishop Vologeses in 359. In that year, Shapur attacked again. The cities around Nisibis were destroyed one by one, and their citizens killed or deported. Constantius II was unable to respond; the campaign of Julian in 363 ended with his death in battle. His army elected Jovian as the new emperor, and to rescue his army, he was forced to surrender Nisibis to Persia (also in 363) and to permit the expulsion of the entire Christian population.

Ephrem, with the others, went first to Amida (Diyarbakır), eventually settling in Edessa (Urhay, in Aramaic) in 363. Ephrem, in his late fifties, applied himself to ministry in his new church and seems to have continued his work as a teacher, perhaps in the School of Edessa. Edessa had been an important center of the Aramaic-speaking world, and the birthplace of a specific Middle Aramaic dialect that came to be known as the Syriac language. The city was rich with rivaling philosophies and religions. Ephrem comments that orthodox Nicene Christians were simply called "Palutians" in Edessa, after a former bishop. Arians, Marcionites, Manichees, Bardaisanites and various gnostic sects proclaimed themselves as the true church. In this confusion, Ephrem wrote a great number of hymns defending Nicene orthodoxy. A later Syriac writer, Jacob of Serugh, wrote that Ephrem rehearsed all-female choirs to sing his hymns set to Syriac folk tunes in the forum of Edessa. After a ten-year residency in Edessa, in his sixties, Ephrem succumbed to the plague as he ministered to its victims. The most reliable date for his death is 9 June 373.

Language

Ephrem the Syriac in a 16th-century Russian illustration

Ephrem the Syriac in a 16th-century Russian illustration

The interior of the Church of Saint Jacob in Nisibis

The interior of the Church of Saint Jacob in Nisibis

Ephrem wrote exclusively in his native Aramaic language, using the local Edessan (Urhaya) dialect, that later came to be known as the Classical Syriac. Ephrem's works contain several endonymic (native) references to his language (Aramaic), homeland (Aram) and people (Arameans). He is therefore known as "the authentic voice of Aramaic Christianity".

In the early stages of modern scholarly studies, it was believed that some examples of the long-standing Greek practice of labeling Aramaic as "Syriac", that are found in the "Cave of Treasures", can be attributed to Ephrem, but later scholarly analyses have shown that the work in question was written much later (c. 600) by an unknown author, thus also showing that Ephrem's original works still belonged to the tradition unaffected by exonymic (foreign) labeling.

One of the early admirers of Ephrem's works, theologian Jacob of Serugh (d. 521), who already belonged to the generation that accepted the custom of a double naming of their language not only as Aramaic (Ārāmāyā) but also as "Syriac" (Suryāyā), wrote a homily (memrā) dedicated to Ephrem, praising him as the crown or wreath of the Arameans (Classical Syriac: ܐܳܪܳܡܳܝܘܬܐ), and the same praise was repeated in early liturgical texts. Only later, under the Greek influence, already prevalent in the works of Theodoret of Cyrus from the middle of the 5th century, it became customary to associate Ephrem with Syriac identity, and label him only as "the Syrian" (Koinē Greek: Ἐφραίμ ὁ Σῦρος), thus blurring his Aramaic self-identification, attested by his own writings and works of other Aramaic-speaking writers, and also by examples from the earliest liturgical tradition.

Some of those problems persisted up to the recent times, even in scholarly literature, as a consequence of several methodological problems within the field of source editing. During the process of critical editing and translation of sources within Syriac studies, some scholars have practiced various forms of arbitrary (and often unexplained) interventions, including the occasional disregard for the importance of original terms, used as endonymic (native) designations for Arameans and their language (ārāmāyā). Such disregard was manifested primarily in translations and commentaries, by replacement of authentic terms with polysemic Syrian/Syriac labels. In previously mentioned memrā, dedicated to Ephrem, one of the terms for Aramean people (Classical Syriac: ܐܳܪܳܡܳܝܘܬܐ / Arameandom) was published correctly in original script of the source, but in the same time it was translated in English as "Syriac nation", and then enlisted among quotations related to "Syrian/Syriac" identity, without any mention of Aramean-related terms in the source. Even when noticed and corrected by some scholars, such replacements of terms continue to create problems for others.

Several translations of his writings exist in Classical Armenian, Coptic, Old Georgian, Koine Greek and other languages. Some of his works are extant only in translation (particularly in Armenian).

Writings

Over four hundred hymns composed by Ephrem still exist. Granted that some have been lost, Ephrem's productivity is not in doubt. The church historian Sozomen credits Ephrem with having written over three million lines. Ephrem combines in his writing a threefold heritage: he draws on the models and methods of early Rabbinic Judaism, he engages skillfully with Greek science and philosophy, and he delights in the Mesopotamian/Persian tradition of mystery symbolism.

The most important of his works are his lyric, teaching hymns (ܡܕܖ̈ܫܐ, madrāšê). These hymns are full of rich, poetic imagery drawn from biblical sources, folk tradition, and other religions and philosophies. The madrāšê are written in stanzas of syllabic verse and employ over fifty different metrical schemes. Each madrāšâ had its qālâ (ܩܠܐ), a traditional tune identified by its opening line. All of these qālê are now lost. It seems that Bardaisan and Mani composed madrāšê, and Ephrem felt that the medium was a suitable tool to use against their claims. The madrāšê are gathered into various hymn cycles. Each group has a title — Carmina Nisibena, On Faith, On Paradise, On Virginity, Against Heresies — but some of these titles do not do justice to the entirety of the collection (for instance, only the first half of the Carmina Nisibena is about Nisibis). Each madrāšâ usually had a refrain (ܥܘܢܝܬܐ, ‘ûnîṯâ), which was repeated after each stanza. Later writers have suggested that the madrāšê were sung by all-women choirs with an accompanying lyre.

Particularly influential were his Hymns Against Heresies. Ephrem used these to warn his flock of the heresies that threatened to divide the early church. He lamented that the faithful were "tossed to and fro and carried around with every wind of doctrine, by the cunning of men, by their craftiness and deceitful wiles" (Eph 4:14). He devised hymns laden with doctrinal details to inoculate right-thinking Christians against heresies such as docetism. The Hymns Against Heresies employ colourful metaphors to describe the Incarnation of Christ as fully human and divine. Ephrem asserts that Christ's unity of humanity and divinity represents peace, perfection and salvation; in contrast, docetism and other heresies sought to divide or reduce Christ's nature and, in doing so, rend and devalue Christ's followers with their false teachings.

Ephrem also wrote verse homilies (ܡܐܡܖ̈ܐ, mêmrê). These sermons in poetry are far fewer in number than the madrāšê. The mêmrê were written in a heptosyllabic couplets (pairs of lines of seven syllables each).

The third category of Ephrem's writings is his prose work. He wrote a biblical commentary on the Diatessaron (the single gospel harmony of the early Syriac church), the Syriac original of which was found in 1957. His Commentary on Genesis and Exodus is an exegesis of Genesis and Exodus. Some fragments exist in Armenian of his commentaries on the Acts of the Apostles and Pauline Epistles.

He also wrote refutations against Bardaisan, Mani, Marcion and others.

Syriac churches still use many of Ephrem's hymns as part of the annual cycle of worship. However, most of these liturgical hymns are edited and conflated versions of the originals.

The most complete, critical text of authentic Ephrem was compiled between 1955 and 1979 by Dom Edmund Beck, OSB, as part of the Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium.

Ephrem is attributed with writing hagiographies such as The Life of Saint Mary the Harlot, though this credit is called into question.

One of works attributed to Ephrem was the Cave of Treasures, written by a much later but unknown author, who lived at the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century.

Symbols and metaphors

Ephrem's writings contain a rich variety of symbols and metaphors. Christopher Buck gives a summary of analysis of a selection of six key scenarios (the way, robe of glory, sons and daughters of the Covenant, wedding feast, harrowing of hell, Noah’s Ark/Mariner) and six root metaphors (physician, medicine of life, mirror, pearl, Tree of life, paradise).

Greek Ephrem

Ephrem's meditations on the symbols of Christian faith and his stand against heresy made him a popular source of inspiration throughout the church. There is a huge corpus of Ephrem pseudepigraphy and legendary hagiography in many languages. Some of these compositions are in verse, often mimicking Ephrem's heptasyllabic couplets.

There is a very large number of works by "Ephrem" extant in Greek. In the literature this material is often referred to as "Greek Ephrem", or Ephraem Graecus (as opposed to the real Ephrem the Syrian), as if it was by a single author. This is not the case, but the term is used for convenience. Some texts are in fact Greek translations of genuine works by Ephrem. Most are not. The best known of these writings is the Prayer of Saint Ephrem, which is recited at every service during Great Lent and other fasting periods in Eastern Christianity.

There are also works by "Ephrem" in Latin, Slavonic and Arabic. "Ephrem Latinus" is the term given to Latin translations of "Ephrem Graecus". None is by Ephrem the Syrian. "Pseudo Ephrem Latinus" is the name given to Latin works under the name of Ephrem which are imitations of the style of Ephrem Latinus.

There has been very little critical examination of any of these works. They were edited uncritically by Assemani, and there is also a modern Greek edition by Phrantzolas.

Veneration as a saint

Saints Ephrem (right) George (top) and John Damascene on a 14th-century triptych

Saints Ephrem (right) George (top) and John Damascene on a 14th-century triptych

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

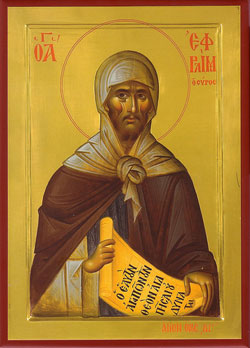

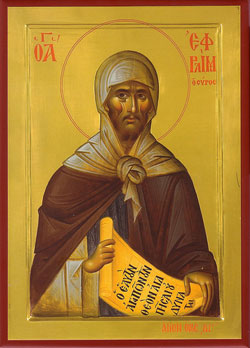

Contemporary Romanian icon (2005)

Contemporary Romanian icon (2005)

Soon after Ephrem's death, legendary accounts of his life began to circulate. One of the earlier "modifications" is the statement that Ephrem's father was a pagan priest of Abnil or Abizal. However, internal evidence from his authentic writings suggest that he was raised by Christian parents.

The second legend attached to Ephrem is that he was a monk. In Ephrem's day, monasticism was in its infancy in Egypt. He seems to have been a part of the members of the covenant, a close-knit, urban community of Christians that had "covenanted" themselves to service and had refrained from sexual activity. Some of the Syriac terms that Ephrem used to describe his community were later used to describe monastic communities, but the assertion that he was a monk is anachronistic. Later hagiographers often painted a picture of Ephrem as an extreme ascetic, but the internal evidence of his authentic writings show him to have had a very active role, both within his church community and through witness to those outside of it.

Ephrem is venerated as an example of monastic discipline in Eastern Christianity. In the Eastern Orthodox scheme of hagiography, Ephrem is counted as a Venerable Father (i.e., a sainted monk). His feast day is celebrated on 28 January and on the Saturday of the Venerable Fathers (Cheesefare Saturday), which is the Saturday before the beginning of Great Lent.

Ephrem is popularly believed to have taken legendary journeys. In one of these he visits Basil of Caesarea. This links the Syrian Ephrem with the Cappadocian Fathers and is an important theological bridge between the spiritual view of the two, who held much in common. Ephrem is also supposed to have visited Saint Pishoy in the monasteries of Scetes in Egypt. As with the legendary visit with Basil, this visit is a theological bridge between the origins of monasticism and its spread throughout the church.

On 5 October 1920, Pope Benedict XV proclaimed Ephrem a Doctor of the Church ("Doctor of the Syrians"). This proclamation was made before critical editions of Ephrem's authentic writings were available.

The most popular title for Ephrem is Harp of the Spirit (Syriac: ܟܢܪܐ ܕܪܘܚܐ, Kenārâ d-Rûḥâ). He is also referred to as the Deacon of Edessa, the Sun of the Syrians and a Pillar of the Church.

His Roman Catholic feast day of 9 June conforms to his date of death. For 48 years (1920–1969), it was on 18 June, and this date is still observed in the Extraordinary Form.

Ephrem is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on June 10.

Ephrem is remembered in the Church of England with a commemoration on 9 June.

Translations

- San Efrén de Nísibis Himnos de Navidad y Epifanía, by Efrem Yildiz Sadak Madrid, 2016 (in Spanish). ISBN 978-84-285-5235-6

- Sancti Patris Nostri Ephraem Syri opera omnia quae exstant (3 vol), by Peter Ambarach Roma, 1737–1743.

- St. Ephrem Hymns on Paradise, translated by Sebastian Brock (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1990). ISBN 0-88141-076-4

- St. Ephrem the Syrian Commentary on Genesis, Commentary on Exodus, Homily on our Lord, Letter to Publius, translated by Edward G. Mathews Jr., and Joseph P. Amar. Ed. by Kathleen McVey. (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1994). ISBN 978-0-8132-1421-4

- St. Ephrem the Syrian The Hymns on Faith, translated by Jeffrey Wickes. (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2015). ISBN 978-0-8132-2735-1

- Ephrem the Syrian Hymns, introduced by John Meyendorff, translated by Kathleen E. McVey. (New York: Paulist Press, 1989) ISBN 0-8091-3093-9

- Saint Ephrem's Commentary on Tatian's Diatessaron: An English Translation of Chester Beatty Syriac MS 709 with Introduction and Notes, translated by Carmel McCarthy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).